How have Western artists discovered and depicted the ideal body since the Renaissance? Michelangelo was the first to express the movement of muscles. Raphael, Dürer, and Rembrandt followed Michelangelo's ideas and adopted different rules. By the beginning of the 20th century, the works of Klimt and Schiele marked the decline of the classics.

The Paper has learned that "Michelangelo and Beyond" being held at the Albertina Museum in Vienna begins with the Renaissance and explores Michelangelo's rediscovery of the ideal body concept in ancient Greece and Rome, and his role in the human body. Revolutionary advances in depiction, and subsequent evolution.

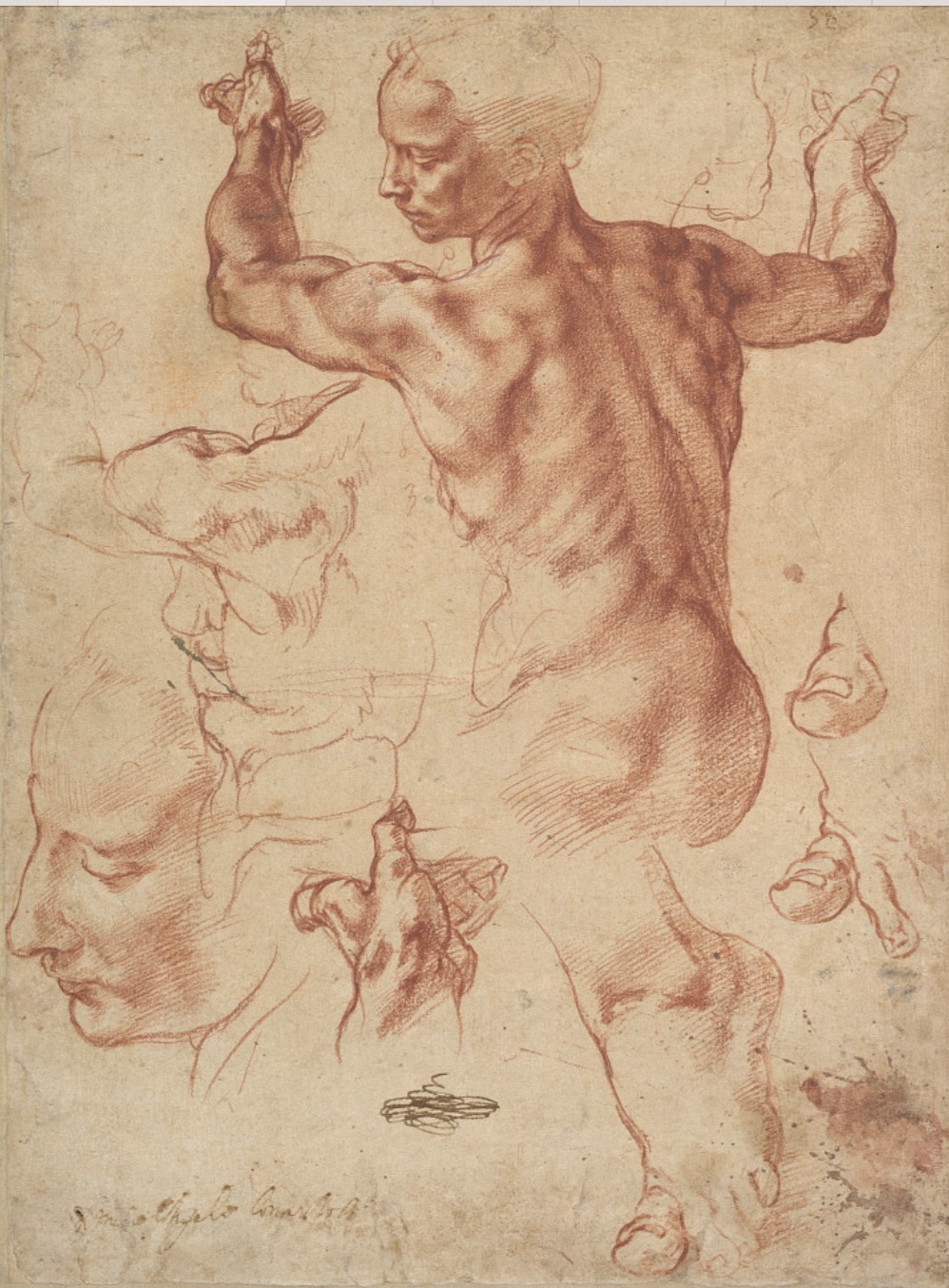

Michelangelo, Study of the Libyan Sibyl, circa 1510/1511, ©bpk/The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Medieval art largely eliminated the mythical and idealized representations of the human form from Greco-Roman times, and was followed by the Renaissance and the "rebirth of the human body." Michelangelo is one of the central figures and the central figure of the exhibition. He is considered the only person during the Renaissance who understood the new perspective on the dynamic body. Among them, some manuscripts of "Battle of Cassina" collected by the Albertina Museum directly reflect Michelangelo's understanding and shaping of body dynamics. In addition, the exhibits also include loans from the Louvre Museum, the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein, etc. exhibition.

Michelangelo's Wrestling

At the beginning of the 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo painted a huge mural of a war scene facing each other in the same large council hall of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence. The two masters competed together, forming the most famous art competition in the Renaissance. .

Palazzo della Signoria and Great Council Chamber in Florence

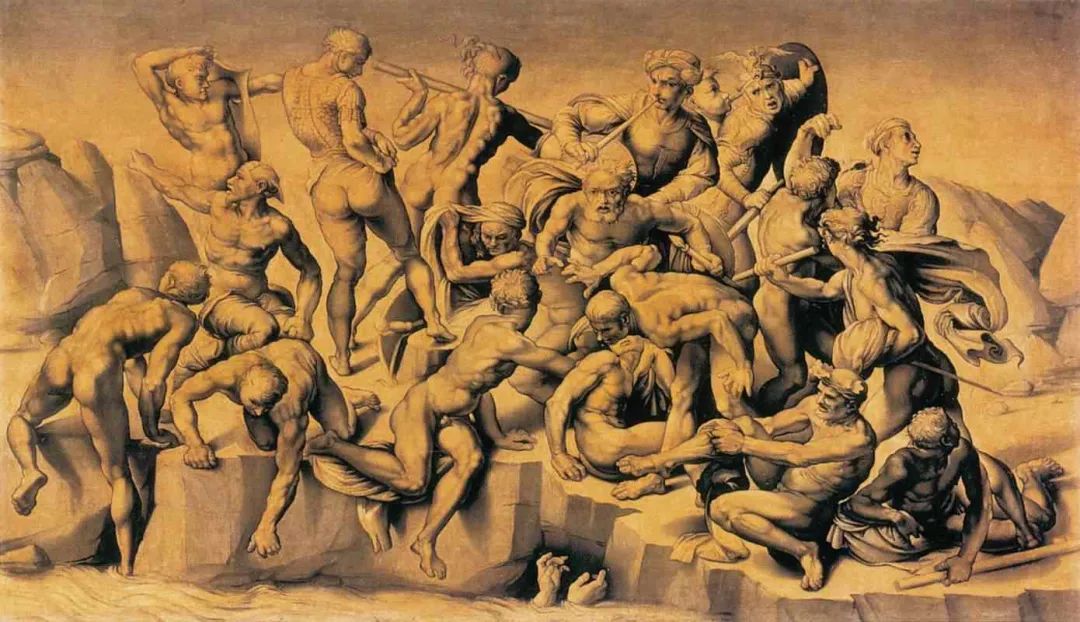

Leonardo da Vinci was responsible for depicting the "Battle of Anghiari", which took place in 1440 and was a battle between Milan and the Florentine Republic. The victorious Florence gained control of central Italy. Michelangelo was commissioned to draw the "Battle of Cassina", which took place in 1364. At that time, Florentine soldiers were bathing in the Arno River. The Pisa army began a surprise attack on the Florentine army. The horn sounded and the soldiers came ashore to enter. fighting. Both battles ended in Florentine victory and have become central to Florentine mythology. However, these two much-anticipated battle scenes (not only the most famous battle scenes of the Renaissance, but perhaps even the most famous battle scenes of all time) were never completed, and many of Michelangelo's sketches have survived. , all preparations for the mural.

The sketch is said to have been publicly displayed at the time, and according to Vasari, almost all Florentine artists, from Andrea del Sarto to Raphael, came to see and study it. These majestic, solemn and tense human bodies make people feel the energy contained within them. No artist had ever painted such heroic figures, with such intricate contortions, such a precise and rich understanding of anatomy, and the figures in these sketches were larger than life-size.

exhibition site

Vasari gave a detailed description of the technique of these sketches. He told us that the sketch was done in black chalk, with some areas highlighted in white; however, the original sketch has been lost, having been cut out by the artist. In the 17th century, some fragments appeared in a collection in Turin. Surviving is a gray-toned copy at Holkham Hall, Norfolk, attributed to Sebastiano da Sangallo, possibly Vasari A copy is mentioned. This reproduction depicts only the central part of the scene. Vasari's description shows a battle between the cavalry on the left and the enemy and the Florentine army on the right.

Sebastiano da Zangalo, The Battle of Cassina (partially based on a painting by Michelangelo), monochrome oil on wood, circa 1542, now on display at Houck, Norfolk, England Han Hall (not an exhibit in this exhibition)

During the Renaissance, artists (including Raphael and Michelangelo), after receiving important commissions, often crafted multiple versions of preparatory drawings and layouts of compositions. In these sketches, you can see the evolution from the original idea. Changes to a more defined sketch plan. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence has a preliminary composition for the Battle of Cascina, and comparing it with what is known today, we can surmise that Michelangelo changed his mind several times. He seems to have developed the composition step by step, gradually changing his ideas as the work progressed; however, only fragments of the original sketches have survived today, so we can only partially reconstruct the complex history of the creation of The Battle of Cassina .

In the early stages of his creation, Michelangelo seems to have been greatly influenced by Leonardo da Vinci's depictions of cavalry battle scenes. But as his work progressed, he arrived at an entirely independent and unique scheme that is now known as The Battle of Cassina. The sketch of the nude from the back on display in the Albertina Museum is a later product of the preparatory work. At this point, Michelangelo had a clear idea of the overall layout and made a detailed overall sketch showing the positions of the figures; he later made sketches of individual figures. Their poses are almost identical to the final version. They are richly detailed, with all muscles under tension and body dynamics equally fine. However, it can be seen in the way the head is drawn in one sketch that Michelangelo slightly adjusted the outline of the face, thus changing the direction of the head so that it faces away from the viewer, adding to the effect of perspective. The right arm is only partially completed as it overlaps the adjacent figure in the finished piece. Michelangelo was only concerned with the visible parts of the composition.

Michelangelo, Male Nude Viewed from Behind, circa 1504, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

On the other side of the paper, Michelangelo used pen and ink to draw two separate figures. On the left he outlined it with a light black chalk, then carved it with pen and ink. This figure is located in the very center of the composition. This may be a depiction of Manno Donati, the soldier who sounded the alarm when the Pisa attacked. This is the only figure in the sketch facing the audience; the figure on the right side of the paper should be at the right edge of the group.

Michelangelo, Study of a Nude of a Man Charging Forward and a Man Turning to the Right (Study of the Battle of Cassina), circa 1504, Albertina Museum, Vienna

The figures in the sketches are mostly outlined with body outlines in colored chalk, and then deeply delineated with ink pens, apparently focusing only on the body. Michelangelo may have also made separate sketches focusing on the heads of figures, but we have seen no such examples.

Often on one side of the sketch, Michelangelo drew meticulous lines with precise, analytical detail in ink pen that could not be altered or corrected. But on the other hand, he would use pastels, which have a softer, more painterly texture. You can see subtle changes in tones in the dark areas, and although there is less detail in the lines, it leaves a stronger impression in the fluidity of the back and the movement of the muscles.

Michelangelo used black chalk lines to create a sense of fluidity and convey the movement of muscles

From 1503 onwards, Michelangelo preferred to use pastels, which made the body more painterly and monumental. The Battle of Cassina is the first time in Michelangelo's career that a figure turns and twists around its own axis. In his early works, such as the marble statue of David (1501-1504), the focus is often fixed on one side. In the composition of "Battle of Cassina" you can see the movement into the space, and the pastels make it more harmonious with the characters and the surrounding space. The drama of these movements is accentuated in the white areas, enhancing the contrast visible on the back. Michelangelo often used this white highlight-like brightening, which Vasari said was the finishing touch to his sketches. These small white areas mark a muscle's highest level of tension. If they were removed, the painting would be overshadowed.

Michelangelo, Study of the Body and Arms of a Seated Young Man, 1510-1511, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

It is worth noting some symbols and lines on these sketches. They are used to correspond to specific muscles in order to illustrate their position from different angles and with different tensions. This method of identifying different muscles may have been later used in cartographic drawings of the Sistine Chapel or even the tomb of Julius II. Michelangelo may also have wanted to provide a detailed description of these "codes" and use them in a scientific elaboration of the human body. According to Michelangelo's biographer Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo intended to write a treatise on all possible postures and movements in human anatomy. Although no article survives, it is clear that the symbols were indeed used to identify specific muscles in the painting.

The respect with which these drawings were treated can be seen in the written marks that appear on these sketches. Michelange's influence extended beyond his time. In the upper right of this sheet you can see the inscription "Collezione di PP Rubens", so this is one of four drawings by Michelangelo owned by Peter Paul Rubens, the great 17th century painter One of the painters, he was also a great collector. On the left, at the bottom of the paper, there is a later inscription: "impossible de trouver plus beau" - it is impossible to find anything more beautiful than this.

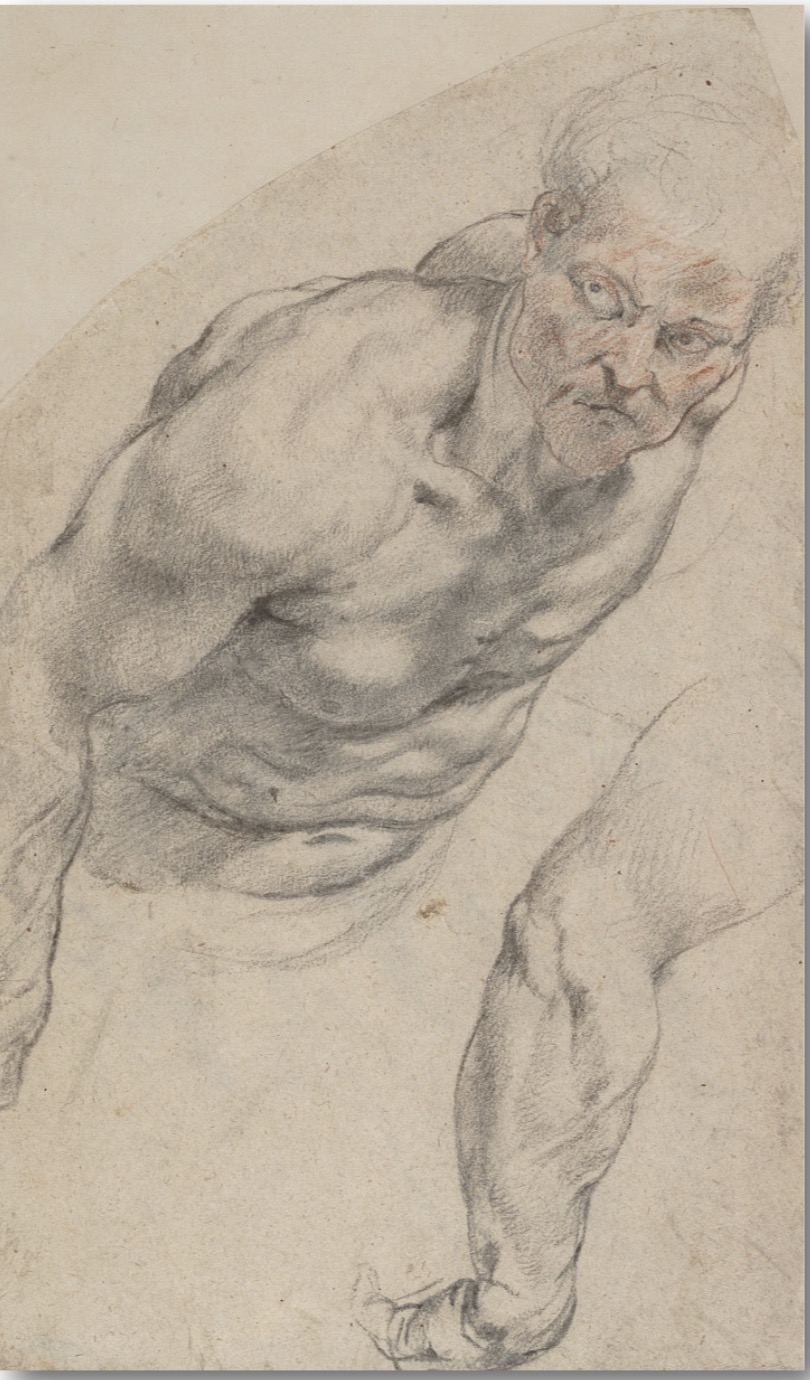

Rubens, Study of a Male Nude Leaning Forward, circa 1613, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

Michelangelo's influence

In fact, there are one or two works in the exhibition that predate Michelangelo to highlight Michelangelo's transcendence - he used pastels, some curves and shadows to create a sense of weight, balance and reality in his works feel.

Michelangelo's depictions of the human body set the standard for representation of the human form and had a profound impact on the history of art. His approach to the human body was not simply to idealize but to capture its complexity and vitality.

Raphael, Young Man Carrying an Old Man, 1514 © Albertina Museum, Vienna

Ugo da Carpi, Diogenes, circa 1527, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

As the artistic movement developed, so did the representation of the human body. From the grandeur of the High Renaissance, to the realism of the Baroque, the sensibility of the Rococo, to the Romantic era’s exploration of the darker and psychological aspects of human nature, artists continue to find new ways to depict the human form.

The exhibition takes viewers into different eras, as well as the works of other artistic icons. For example, Raphael (1483-1520) shared Michelangelo's perspective, and his 1514 work Aeneas and Anchises perfectly captures Aeneas rescuing him from the burning Troy. father's dynamics, and the age difference between father and son.

Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

Dürer (1471-1528) made various attempts at regularity and proportion of the human form, but seems less successful; Rembrandt (1606-1669) had a more realist approach (as in Albertina's Wall Text Described as "ruthless realism"), Rembrandt's candidness almost feels soothing and more real after the perfect human body created by the Renaissance. "Standing Man", which he created around 1648, uses a few strokes to create a male image.

Rembrandt, Woman Seated on a Mound, circa 1631, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

While they drew inspiration from Michelangelo's seminal works and incorporated his ideas into their own styles and artistic backgrounds, they produced different interpretations of the human body and developed a unique view of the human body.

Charles-Joseph Natovar, Bacchus and Tambourine, circa 1740, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

John Peter Pickler. Male Body, 1789, © Albertina Museum, Vienna

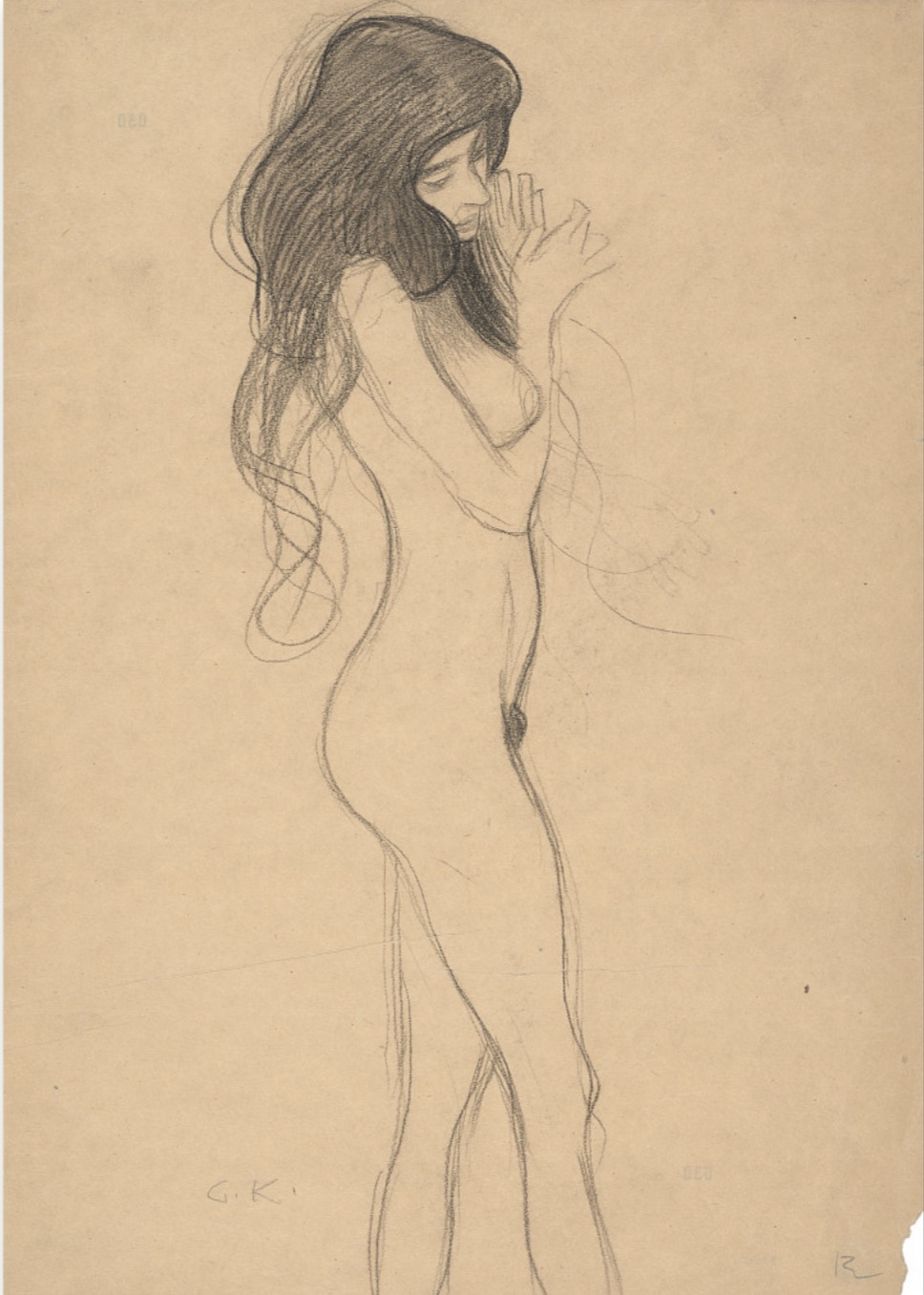

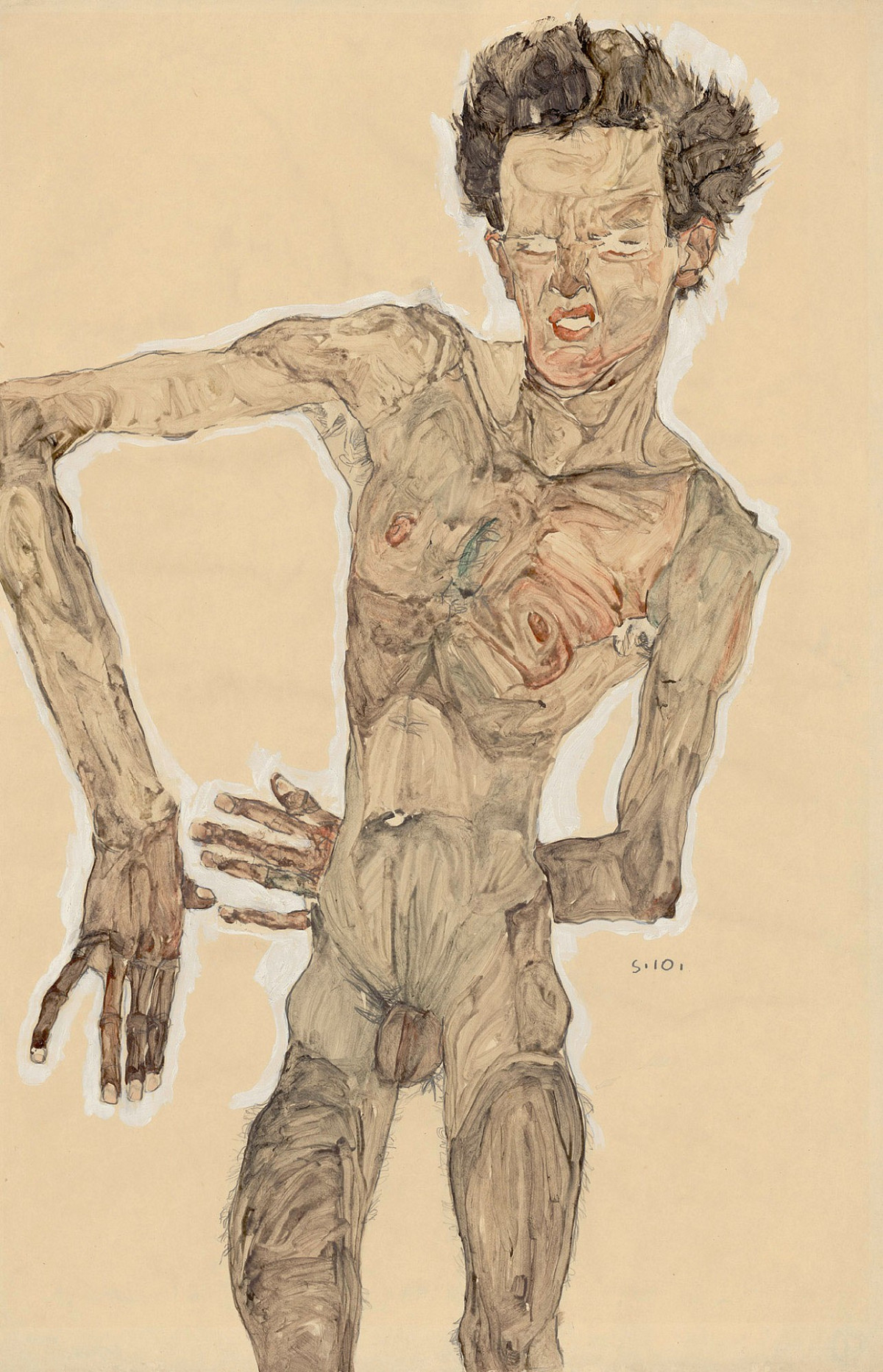

At the end of the exhibition timeline, the works of Klimt (1862-1918) and Schiele (1890-1918) bear witness to a complete departure from traditional ideals of beauty and form. In particular, Schiele's astonishingly angular Self-Portrait is morphologically far removed from Renaissance anatomy. Schiele seemed to have sounded the death knell of the "Michelangelo method". The expression of raw emotions in his works broke through the boundaries of original artistic expression. He also freed women from the demure, seductive image of the past and promoted their power and equality.

Klimt, Study for the Gorgon with Hair, 1901, Albertina Museum, Vienna

Egon Schiele, "Self-Portrait Making a Face", 1910, Albertina Museum, Vienna

In the 16th century, it began with Michelangelo's ideal representation of the human body, rising and falling with the ideas of different centuries. Artists continually reimagine and reinterpret the human form, reflecting the changing cultural, social and artistic trends of the times. In addition to showcasing artistic techniques, the exhibition structure and related texts also explain the evolution of the human body in art.

Note: The exhibition will last until January 14, 2024. This article is compiled from "Apollo Magazine", "Wandering in Vienna" and the Albertina Museum website.