Were there any female artists before the 19th century?

In China, most women, whether it is Duan Sheng in the Yuan Dynasty or Gu Hengbo in the late Ming Dynasty, who are both talented and beautiful, and good at poetry, calligraphy and painting, cannot escape the shackles of the "artistic couple". In the West, most people believe that women first picked up a paintbrush when they fought for the right to vote.

However, if you go back further, you will be surprised that even if the times are limited, there are still women who can build outstanding artistic careers.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait: The Incarnation of Painting, 1638-1639

Starting with the blockbuster Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition at the National Gallery in 2019, a series of exhibitions have brought the names of many Renaissance women into the spotlight. Just this year, the National Gallery of Ireland held "Lavinia Fontana: Trailblazer, Rule Breaker" and the UK's Dulwich Picture Gallery held "Mary Mary Beale: Experimental Secrets, Artemisia Gentileschi: coraggio e passione at Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, Italy, and "Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance" at the National Museum in Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands, among others.

Fontana, Mars and Venus, 1595

These rich exhibitions have made the public aware that women have always been making art, so what should be the next step? Two exhibitions currently on display in the United States may provide some direction, proposing new perspectives on the subject of women and art in the early modern period—Baltimore Museum of Art’s “Leaving Her Mark: A History of European Women, 1400” -1800” (Making Her Mark: A History of Women in Europe, 1400-1800, through January 7) and “Strong Women in Renaissance Italy” (through January 7) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston July 7).

"Leaving Her Mark: A History of Women in Europe, 1400-1800" at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

As several essays in the Baltimore Museum of Art exhibition catalog point out, emphasizing individuals in blockbuster exhibition titles reinforces narratives of excellence—that they are rare, and that only a handful of artists have the opportunity to put their Skills developed into profitable careers.

The return of the “overshadowed” or “forgotten” female artist thus reinforces the narrative of the ideal artist (usually male) as an individual genius. Does not help disrupt broader assumptions about the value of artworks. Because in "Leave Her Mark," curators Andaleeb Badiee Banta and Alexa Greist set out to "find everyday female artists." They look at women's participation in the wider visual arts as craftsmen, makers, overseers and more. Although women's work is difficult to trace due to a lack of signatures and records, the curators have presented an impressive array of objects, with a particular focus on decorative arts such as pottery, embroidery and scientific drawing.

"Leaving Her Mark: A History of Women in Europe, 1400-1800" at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Scholars increasingly recognize that women participate in a variety of industries in both formal and informal capacities. In her study of British youth culture in the 16th and 17th centuries, Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos demonstrates that, in the case of Bristol, around 1,500 people from all walks of life Approximately 3.3% of apprentices are female. In London the proportion is lower, but in smaller towns such as Southampton it is much higher at around 10%. Although many apprenticed in traditionally "female" trades such as sewing and domestic service, some found work as drapers, apothecaries, fishmongers, and wine merchants. They were also trained in crafts such as joinery, clockmaking, textiles, leather and metal working. Informally, wives and daughters are often employed in the workshops of male family members, involved in all aspects of work from production to supervision. The exhibition in Baltimore helps give visual and material form to these statistics, showing that many traditionally male trades and workshops often involved women in some way.

Judith Leicester, Self-Portrait, 1633 (Leaving Her Mark: A History of Women in Europe, 1400-1800 exhibit)

“Leave Her Mark” focuses on women as creators, while “Powerful Women of the Italian Renaissance” in Boston takes stock of all the different ways women engage with art. In the exhibition space, continuous areas are separated by colonnades and niches, designed to imitate the famous three paintings of "The Ideal City" created by unknown hands in the 15th century, trying to evoke the ideal publicity of Italian cities. space, emphasizing the influence of women inside and outside the home. They are art creators, writers, composers, patrons, models, designers and users.

One of the first objects on display is a charming self-portrait by Sofonisba Anguissola from 1556. She is shown holding up a disk with a "code" representing her father's name: this is a star show in every sense of the word, but it reminds the viewer that talented female painters often appear in the presence of male relatives. in the studio. This is only one aspect of the exhibition, though: it also covers important female patrons such as Isabella d'este; as well as reviewing material evidence of women's devotional rituals and presenting to unknown A tribute to the women embroiderers, weavers and lacemakers.

Sophonisba Angisola, Small Self-Portrait, 1556 (Exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

One section is devoted to female role models, including figures from the Bible and classical mythology. Plates, paintings and clay sculptures depict women such as Judith, who infiltrated military camps and beheaded enemies, and Sabine women who advocated peace after being kidnapped by Rome's enemies. These women were seen as paragons of virtue and represented characters that women could use to shape their lives. However, for many women, the choice of role model is not limited to gender, and there are no shortage of examples of powerful women comparing themselves to legendary men. For example, after her accession to the throne, Elizabeth I of England compared herself to Daniel emerging from the lion's den, and there are various examples and images and texts depicting her as the wise King Solomon rather than What we might expect from King Solomon's companion, the Queen of Sheba.

Giovanni della Robbia, Judith, circa 1520 (exhibited in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

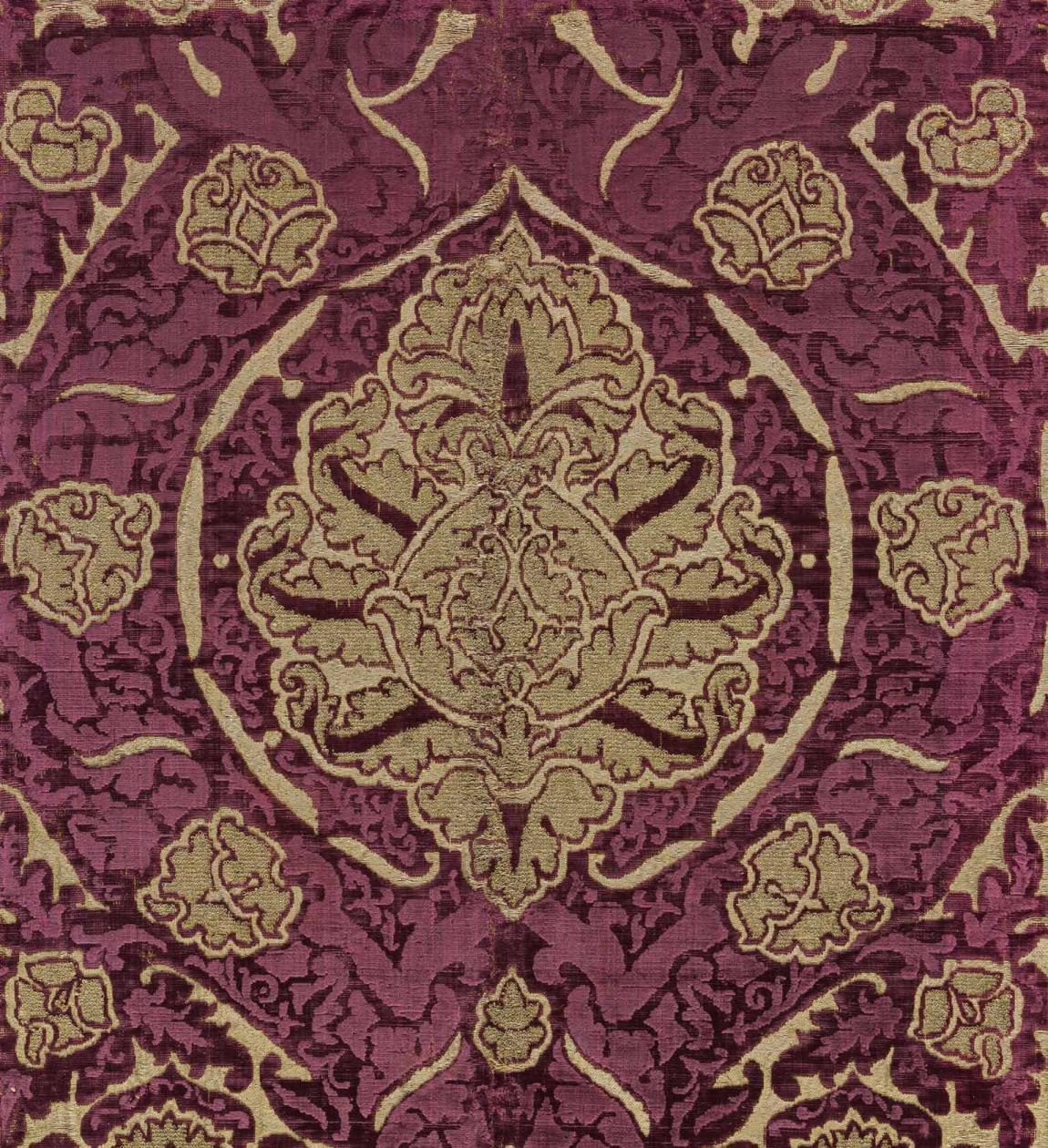

Both the Boston and Baltimore exhibitions blended traditional art such as sculpture and painting with decorative arts such as ceramics, lace and embroidery. In the exhibition, delicate embroideries and woven velvets are hung as easel artworks that look at home among more traditional oil portraits and history paintings. In the Baltimore exhibition catalogue, this approach is presented as a feminist act—a rejection of the doctrine of "power on the walls" in the museum setting. This doctrine (the curators believe) favored masculine styles of painting over feminine styles of beadwork and embroidery. However, as visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Rijksmuseum will know, the combination of fine and decorative arts is the key to today's displays of Renaissance and early modern works. standard practice.

In a museum setting, the origins of this mixed approach can be traced to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, where Michael Jaffé established a country house-style exhibition in the 1970s. In the past 30 years, this approach has generated renewed interest with the opening of the V&A Museum's groundbreaking British Galleries 1500-1900 in 1998. There, furniture, textiles, ceramics, paintings and more are displayed together in the same themed rooms, rather than separated by genre or material. This was based on the values of the times and helped convey richness and diversity to the audiences of the time. This resulted in the same overall multimedia gallery experience as in Boston and Baltimore, but with a rationale that prioritized historically accurate annotation.

Anonymous, Velvet Weaving (detail), Italy, 15th century (Exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

In fact, for female artists during the Renaissance, returning to the values of the era may face several problems. One of the main issues is the quality of the work. It goes without saying that female artists were generally denied the same critical training as their male counterparts—especially anatomical studies and figure drawing based on the male nude. As the curators of the Baltimore exhibition point out, we now know that while some women had access to naked male models, they could use their own bodies to create female figures. But historical facts can help explain the obstacles faced by women engaged in historical and narrative painting, whose grasp of anatomical proportions and dynamics was often criticized as poor technique.

Sofonisba Angisola, "Chess Game", 1555, Collection of the Museum in Poznań, Poland (Exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Yet how to deal with this difference in quality also troubles the textual narrative of the Baltimore exhibition. Sofonisba Anguissola's painting Boy Bitten by a Crayfish (c. 1554) is considered a rare example of a work by a female artist that Vasari praised, but Vasari praised Not the technique itself, but the exquisite depiction of human emotion. Originality is also an issue faced by female artists, and the curators of both exhibitions did not deny the fact that many female artists plagiarized the work of others. However, for most pre-modern artists (including male artists), originality was hardly the key. The word "invention" comes from the Latin invenire, which means discovery or acquisition, as well as invention in the familiar sense. Copying the work of others was an important part of an artist's training, and all decorative artists derived their designs from engravings and engravings.

Pietà Embroidery, 16th Century (Exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Is "pure" plagiarism particularly relevant to women? maybe. In a Pietà scene currently on display in Boston, embroidered by an unknown woman, the upper border is decorated with an image of Veronica's veil. This is Jesus on his way to the crucifixion. Veronica, a believer on the roadside, presented her veil to Christ. So miraculously there is the face of Christ on the veil. The veil is generally an image "made" by women, which suggests a magical and mechanical process of reproduction without originality or creativity. Likewise, the four corners of the frame depict a healthy male cherub, possibly to "shape" the baby in the mother's womb through an unconscious process known as "maternal impressions," where it is believed that what the mother sees, Can affect the "shaping" of the baby in the womb.

Artemisia Gentileschi, The Sleeping Child, 1630-1632 (Exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

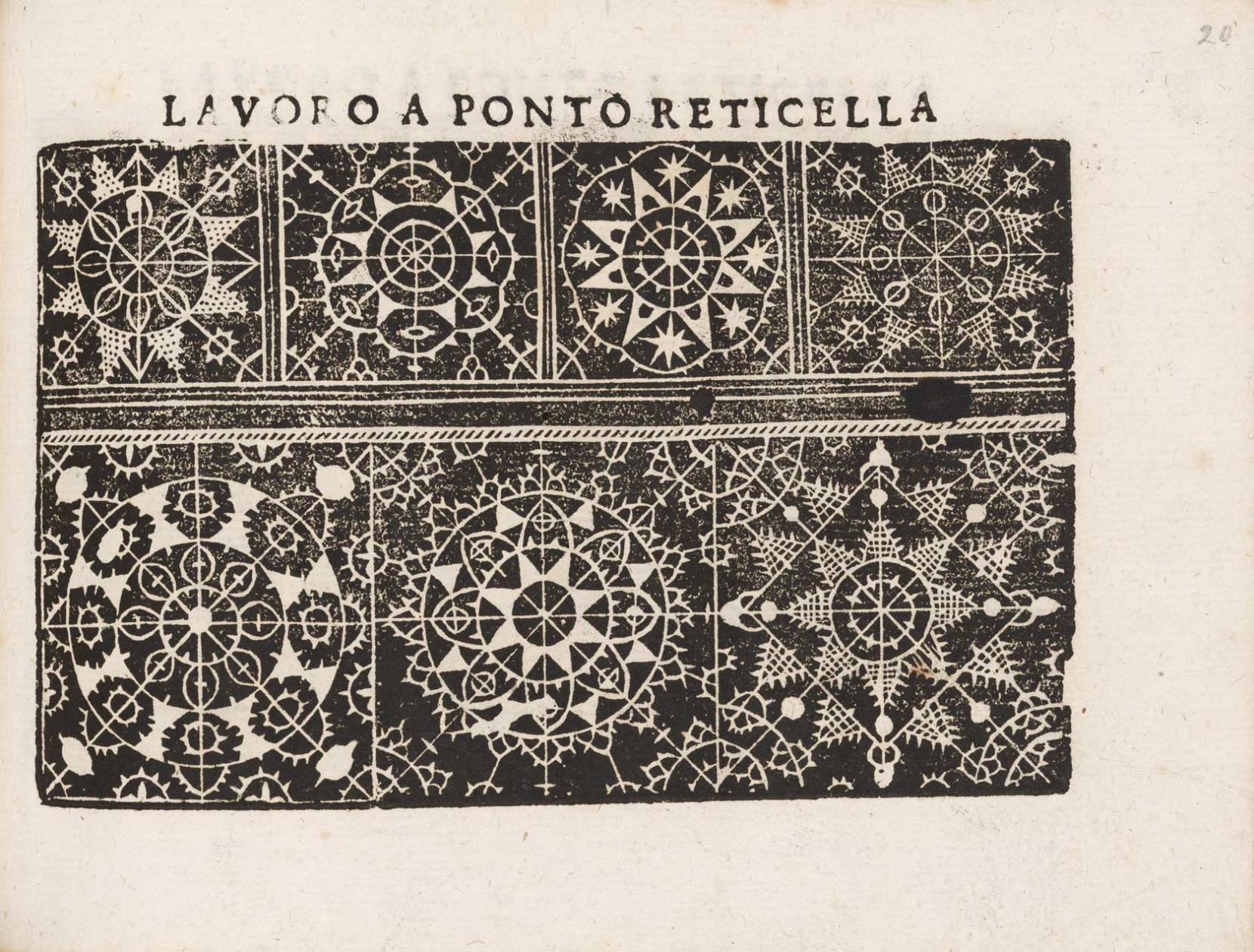

A book of lace patterns by Isabella Parasole (1575-1625), also on display in Boston, is an example of women reinventing patterns rather than copying them. Just like men, some women produce amazingly high-quality work, while others don't. The historical reasons are worth exploring.

Isabella Palazzo's Book of Lace Patterns, 1625. Included are 38 pages of woodcuts. (Exhibits at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

But rather than psychologically comparing women to outstanding men (like Raphael, Michelangelo), perhaps they should be viewed within the larger context of human creativity. In fact, there are many “ordinary” male artists, which is what the Baltimore exhibition suggests, but there is room for further exploration. Women have always been making things and we need to do them justice and not impose anachronistic constraints. Reveal more of a rich and unfamiliar past to see the power of women to their fullest.

Note: This article is compiled from the December issue of "Apollo Magazine"