Cycladic culture is an early Bronze Age civilization found on the Cyclades Islands in the Aegean Sea. It is best known for its marble statues and existed roughly from 3000 BC to 1000 BC.

Recently, a large-scale Greek Cycladic Civilization Collection will be permanently located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, allowing the public to understand the basic appearance of early Greek sculptures and the derivative forms resulting from their continuous development.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, USA, has added another dazzling pearl to its dazzling display of cultural relics. But this jewel takes up only a modestly sized exhibition wall in the museum. You can find this wall in the Belfer Court, the first on the right after entering the Greek and Roman Gallery from the Great Hall. If you go too fast, you might miss it. Slow down and prepare to be wowed by the largest collection of ancient sculptures from the Greek Cyclades Islands ever seen in New York. The exhibition is titled "Cycladic Art: An Exhibition from the Leonard N. Stern Collection."

This statue of a serene female is one of the largest Cycladic statues on display at the Metropolitan Museum and was made between 2700 and 2400/2300 BC. The artwork was discovered with fractures at the neck and knees, and traces of red paint remaining on the neck of the torso.

Five large glass cabinets hang on the wall. Each cabinet typically has three shelves, and the red felt interior is set against gleaming white marble carvings, including 120 ancient Greek figures and vessels. The shelves are dominated by about 70 small, exquisite female statues or "portraits," with an average height of about 16 inches, including a rare statue over 4 feet tall. These sculptures are the brilliance of Cycladic art in ancient Greece. They are characterized by unique shapes, folded arms, and small wedge-shaped noses on the faces, but they have no expression. They are low-key and show a sense of tranquility.

Some of the marble statues and vessels on display in the exhibition "Cycladic Art"

There are also some relatively large free-standing heads in the glass display cases, which have no bodies, much like miniature versions of the giant heads on Easter Island. There are also many vessels: vases, bowls, plates and some palettes, two of which are narrow, delicate, slightly curved and seem to be cut from a leek leaf. Five other exhibits are displayed in five nearby glass display cases, while a further 36 exhibits are displayed in a glass display case in the Greek and Roman Research Collection on the mezzanine, overlooking Leon. Leon Levy and Shelby White Court.

All 161 pieces were made in the Greek Cyclades Islands. The Cyclades are a group of islands in the Aegean Sea east of Greece, and the artwork was produced between approximately 5300 BC (the late Neolithic Age) and 2300 BC (the early Bronze Age). This period is also known as the Early Cycladic I and II periods. These human statues are one of mankind's greatest artistic achievements. They are serious and cold, yet instantly familiar. They are lifelike in nature, like skeletal specimens. They appear to be foldable, like dummies in a drawing.

In the display cabinet, four marble female statues are unique in shape, with arms folded and expressionless faces.

The artworks were collected by Hartz Mountain Industries CEO Leonard N. Stern starting in the 1980s. As a teenager, Leonard was fascinated by the Cycladic art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He later donated his collection to Greece. According to the agreement reached between him, the Metropolitan Museum and the Greek government, most of the collection will remain on display at the Metropolitan Museum for the next 25 years, and some artworks will be returned to Greece regularly. The exhibition is curated by Sean Hemingway, head of the Met’s Department of Greece and Rome, and Alexis Belis, assistant curator.

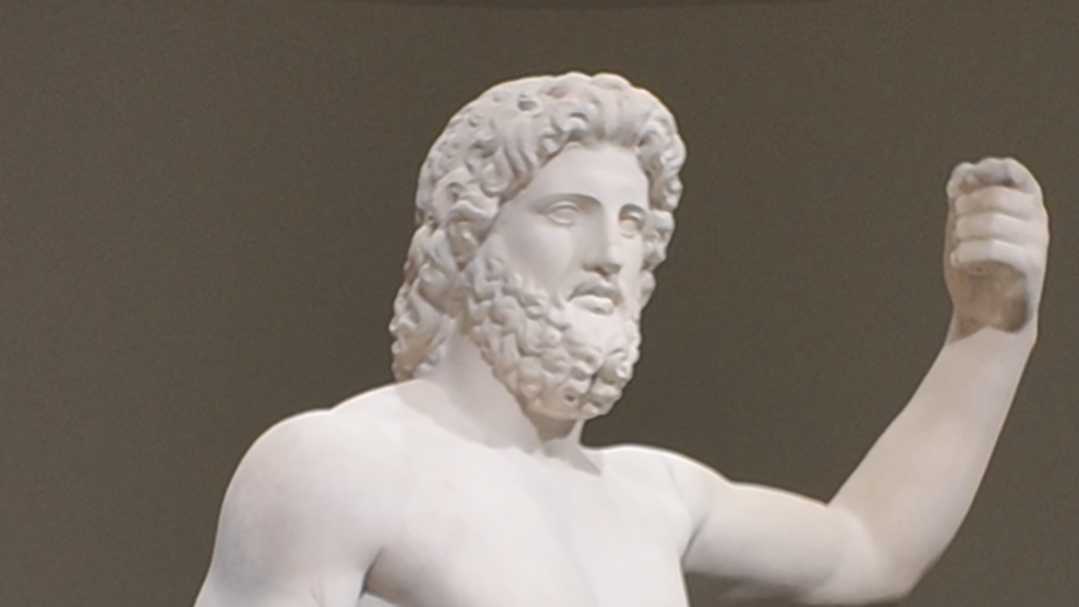

It was Cycladic sculpture that started the great tradition of ancient Greek sculpture. Two thousand years later, classical sculpture from the Golden Age of Greece, centered in Athens, brought this tradition to its zenith. Cycladic sculpture is also an important origin of Western abstract art. Like African sculptures, they are the product of colonial plunder, and before the turn of the 20th century they were housed in the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris, where Brancusi, Modi Modern artists such as Riani and Picasso were important influences.

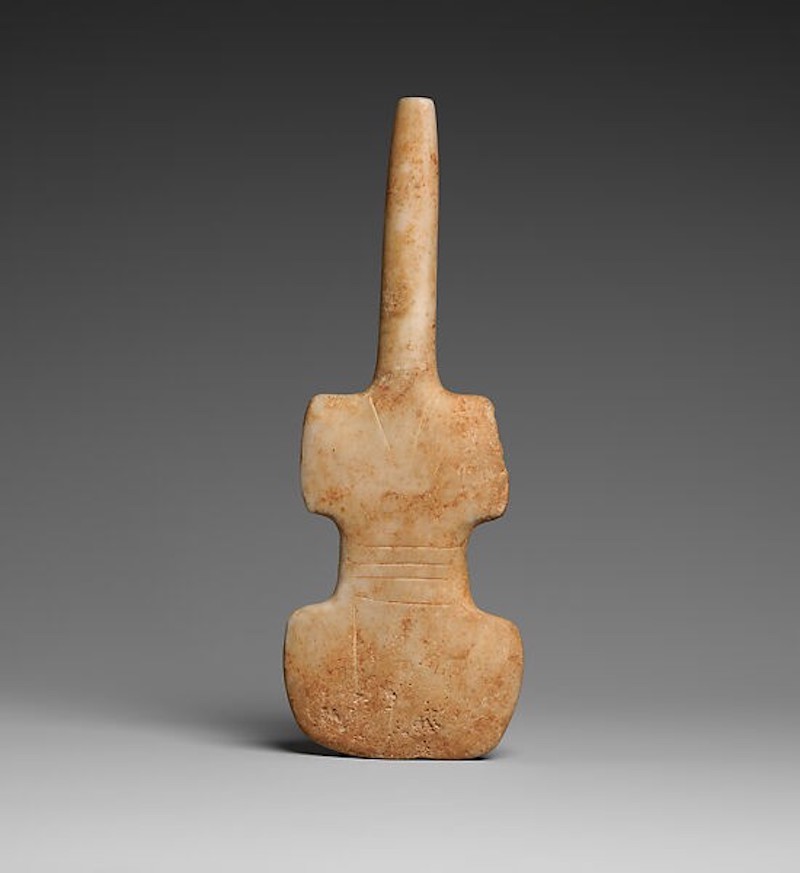

In the first display case of the exhibition hall, the Cycladic style has begun to take shape, (upper level) there are strange arms and brick-like chests; (middle level) there are armless violin-like figures; and (lower level) it is possible to use Reclining figure from a burial ceremony.

The basic stance and posture of Cycladic sculptures rarely changes: their arms are folded in the middle of the torso, one above the other, below the modest breasts. The ends of these arms usually have four short, shallow cuts that look like paintbrushes or tassels, but express the hands. Female figures have inverted triangular cuts on their lower abdomens, somewhat like bikini bottoms, while curves are usually found in the thighs and calves.

Their faces are as smooth as masks, with wedge-shaped noses and slender necks. Their heads are often tilted back, looking up at the stars, even if they are not worshiping, they are meditating. In other cases, the faces of these people look straight ahead, conveying more nuance. For example, some might be almost caricatures of women on the beach in soaking wet bathing suits, shivering and trying to get their children out of the water. Surprisingly, some characters are always reminiscent of New Yorker cartoons.

An early marble female figure from about 3200 BCE to 2700 BCE

The purpose of Cycladic figurines remains largely a mystery. These statues were made in a time before writing. Later, most of the statues were dug up by people in order to sell them for money. These searchers rarely consider the minutiae of archaeology, such as when and where the statues were found, what they were made of, and how deep underground they were. Some of the sculptures were found placed horizontally in tombs and tombs as part of burial rituals. Others may have been fertility idols or were used in private shrines. They may also have been toys, illustrating their great appeal and accessibility. Today, they remain one of the most popular ancient art forms.

For today's art lovers, first encountering a Cycladic statue can be an important rite of passage. This sight makes you realize instantly that what we call modernity is not new. But one part of Cycladic modernity is relatively new: the statues were not originally bare white marble, most were painted. Hence the color palette among the vessels displayed. On some of the statues we can see a hint of carmine and tiny flecks of color, while on some of the plates there are also distinct strokes of pale orange and red.

A marble bowl on the left proves that most Cycladic sculptures were painted, as was the marble figure on the right

Seeing so many statues at such a close distance gives the viewer a sense of shock. We learn that this sculptural formula accommodates an unusual range of proportions, emotions, and body language and encourages a sense of connoisseurship. You can’t help but notice and compare them.

You can almost see the style of these artworks on the top two shelves of the first showcase. The two headless humanoid bodies are in the shape of blocks, guitars, or violins; while the arms of the other two figures are raised on the hips, with small gaps at the elbows, and the chest of one of them is reminiscent of being pressed together. of bricks. A round-butted figure resembles an inflatable bag toy, with hands and arms that are cutely curved and appear to be folded at the armpits.

This is a Cycladic statue from about 2500 BC-2400/2300 BC. The statue has no torso, with crossed arms just below the chin

Sometimes the folded arms look like matchsticks, other times they are more fleshy, even very relaxed, almost natural. The arms of some figures appear unstable when sliding up and down the torso, some look like drapes, and some look like drooping waistlines. The most extreme one is in the last large red-lined glass display case, which is a figure without a torso, so that the crossed arms are just below the chin. The arms are displaced and it looks like the figure is holding a small piece of wood to make a fire.

This collection of Cycladic art also transformed the Balfour Room into one of the Met’s greatest galleries. It is generally believed that the tradition that began with Cycladic sculptors reached its peak many centuries later, as their descendants eventually achieved precise and idealized treatments of the human body. However, I think this idealized realism is lacking, and the Greek sculptural tradition showed greatness in the hands of its Cycladic forefathers.

Female statue, 3200-2700 BC, marble

Handled tall jar, 3200-2700 BC, marble

(This article is compiled from the New York Times. The author, Roberta Smith, is an art critic.)