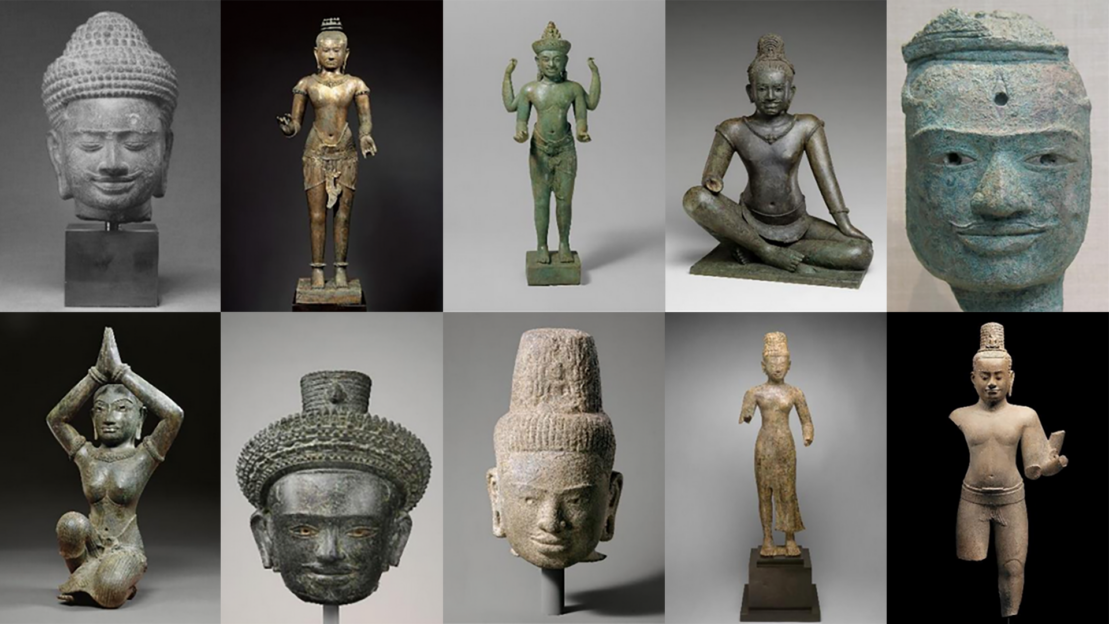

On July 3, 2024, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in the United States officially returned 14 cultural relics to the Cambodian government. On December 15, 2023, the Metropolitan Museum of Art issued a public statement announcing that it would return 16 cultural relics to Cambodia and Thailand, including 14 to Cambodia and 2 to Thailand. This marks that all the Angkor Wat sculptures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art that were smuggled by antique dealer Douglas Latchford have been returned to the Cambodian government.

In recent years, Cambodia has recovered more than 800 cultural relics from all over the world, and the United States is the country that has returned the most cultural relics to Cambodia. The repatriation of cultural relics by the Metropolitan Museum of Art responds to the strong demands of Asian and African countries in recent years to recover cultural relics. In February this year, the documentary "Dahomey" about the return of cultural relics by the French government to the African country of Benin won the Golden Bear Award for Best Film at the Berlin Film Festival, pushing the call for the return of cultural relics to another climax. Behind the return of cultural relics is the reflection of judicial institutions, administrative departments, museums and collectors in European and American countries on the ownership of historical cultural relics in the current geopolitical context.

Theft and smuggling of Khmer cultural relics

Compared with African cultural relics that have been scattered in European national museums for more than 200 years, the loss of Cambodian cultural relics is more recent. The 1970s to 1990s were the peak period of Cambodian cultural relic smuggling, which was called "the largest art theft in history" by American lawyer Brad Gordon. During the rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, cultural relic thieves took advantage of the domestic unrest in Cambodia to steal a large number of stone sculptures from more than 4,000 temples across the country. Among them, the largest cultural relic smuggler who has been identified is antique dealer Douglas Reichford. In 2019, the US prosecutors indicted Douglas Reichford for cultural relic smuggling, but the latter died in 2020 and the lawsuit ended.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara Seated in Royal Ease, 10th-11th century, Cambodia, acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1992, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024. Photo: MET

The Cambodian cultural relics smuggled by Redchford were widely distributed among wealthy private collectors, and were eventually collected by many large museums in Europe and the United States through auctions or donations. In 2021, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) resumed its investigation into the Redchford cultural relics smuggling case. This organization, founded in the United States in 1997 and with more than 160 journalists, pointed out through collaborative in-depth investigations that many large museums had obtained smuggled cultural relics from Redchford.

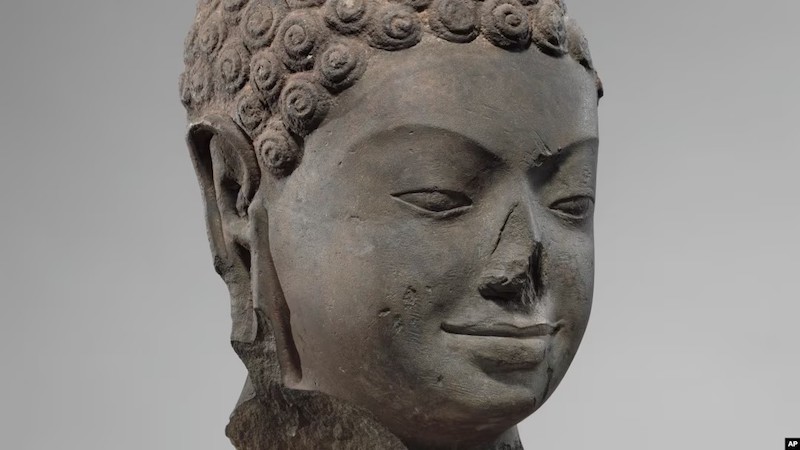

Head of Buddha, 7th century, southern Cambodia, acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2005, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024 Photo: AP

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has dozens of pieces, the Denver Art Museum has 15 pieces, and the British Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the National Gallery of Australia also have collections. In the Pandora Paper, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists also pointed out that the Redchford family evaded taxes and did not pay inheritance tax on cultural relics to the British government.

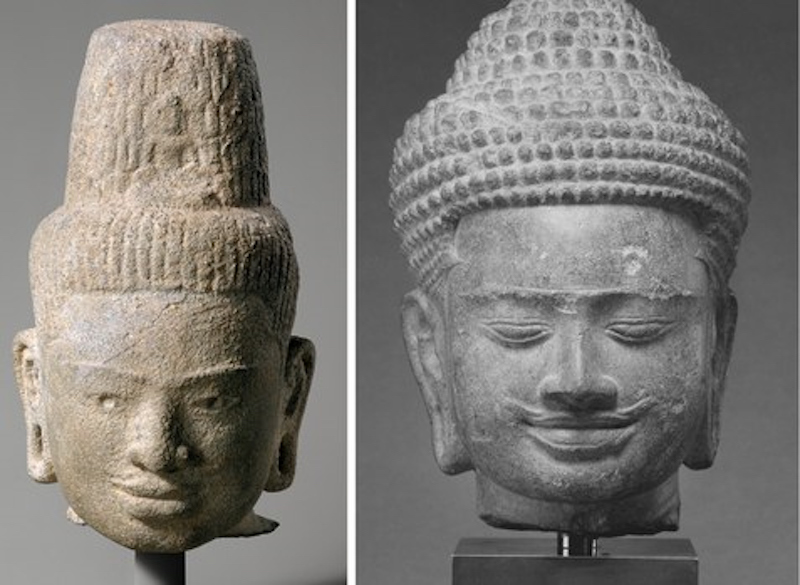

Left: Head of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, late 7th century, central Cambodia, acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1997, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024. Photo: MET

Right: Head of a Buddha, Cambodia, collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1983, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024. Photo: MET

Under pressure from many parties, the Reichford family decided to return the cultural relics. In 2022, Reichford's daughter Nawapan Kriangsak negotiated with the National Museum of Cambodia to return the collection worth $50 million. In 2023, Nawapan returned 125 cultural relics to the Cambodian government, worth $12 million.

The Khmer servant kneeling statue returned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013. Image: DW

The US judicial authorities have also investigated the smuggling of Cambodian cultural relics and initiated judicial proceedings. Various institutions have successively returned cultural relics to Cambodia in batches. In 2023, the Denver Art Museum returned four cultural relics to Cambodia, three of which were Khmer sculptures from the 7th to 12th centuries, and one was a Dong Son bronze bell from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD; in August 2022, the United States returned 30 looted cultural relics to Cambodia, including Buddhist and Hindu statues; in 2021, the Manhattan District Attorney's Office in New York returned 27 looted cultural relics to Cambodia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art last returned cultural relics to Cambodia in 2013, when two 10th-century Khmer servant kneeling statues were sent back to Cambodia.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara Padmapani and Attendants, collected by the National Museum of Australia in 2011, returned to Cambodia in August 2023. Photo: National Museum of Australia

In August 2023, the National Museum of Australia announced the return of Khmer cultural relics worth US$1.5 million that it had obtained from Reicheld in 2011. Reicheld had insisted on signing a confidentiality agreement before delivery, otherwise he refused to provide information on the origin of the cultural relics.

However, only three museums have returned the cultural relics smuggled by Redchford to Cambodia, and other museums are still vague. According to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the Brooklyn Museum, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, and the Art Gallery of NSW also obtained the cultural relics smuggled by Redchford through donation or purchase. These three institutions responded to the reporter's inquiries, but none of them promised to return the cultural relics, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art refused to respond to the reporter's investigation.

The King of Smuggling, in the Name of Protection

"The collection exceeds that of the National Museum of Cambodia" is the most famous rumor about Redchorford, which may not be groundless.

National Museum of Cambodia exterior photography: Laura Shen

In 2016, I visited the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. This red-brick tropical courtyard has scattered cultural relics, and the interior is cooled by electric fans. Whether it is the use of space, the placement of cultural relics, restoration and protection, or the level of curatorial work, it does not match the national museum of an ancient civilization. This is different from the Khmer art collections in American museums and institutions, which are preserved in a more complete collection, preservation, research and curatorial system.

National Museum of Cambodia interior Photography: Laura Shen

"I am not plundering cultural relics, I am protecting them. If it weren't for me, these cultural relics would have long since disappeared," said Douglas Reichford. To some extent, what he said was not entirely wrong. In Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge regime, even without Reichford, there were other people who sold cultural relics, including the Khmer Rouge regime itself. The Khmer Rouge guards who occupied Angkor Wat not only destroyed the stone carvings, but also made profits by selling them. At that time, no one thought it was "illegal."

Angkor Wat during the Khmer Rouge period: Cambridge University Press

"Many ordinary people we met in Africa said that they were not interested in taking back all the artifacts from French museums because some of them could be used to spread African culture," said Bénédict Savoy, an art historian who has long been dedicated to the repatriation of looted artifacts. If French naturalist Henri Mouhot discovered Angkor Wat for the world in 1861, then to some extent, Reichford promoted Khmer art to the world. He is undeniably an outstanding art historian and archaeologist.

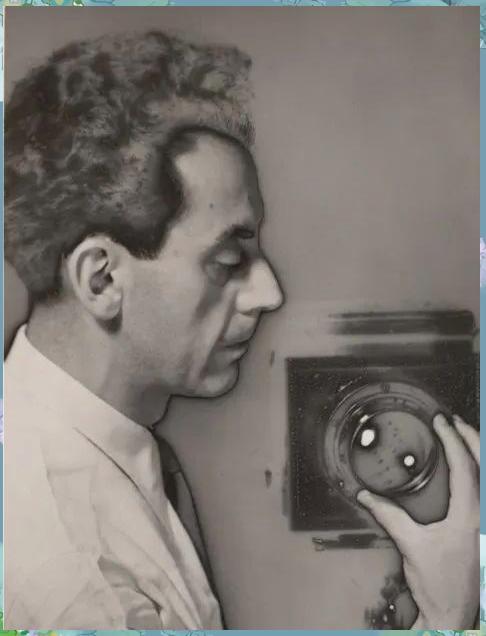

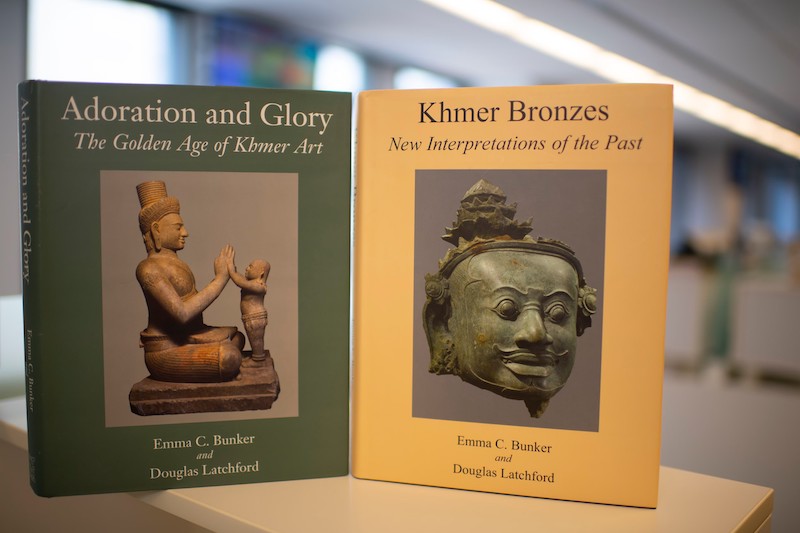

Douglas Redchford's work on Khmer art history. Photo: Washington Post

Ironically, when the Cambodian government tried to recover the stolen artifacts, it could only rely on the book of the “thief” Douglas Redchford to trace the artifacts back to their source. Many of the artifacts he described in his book were never seen by Cambodians themselves.

Cambodian archaeologists rely on the work of Raychford to trace the origins of cultural relics. Photo: CBS

Reichford himself has a strong "post-colonial" flavor. He is an Asianized native white man with dual British and Thai citizenship. Born in Mumbai, British India in 1931, he was educated in Britain, returned to India after India's independence, moved to Bangkok, Thailand in 1956, became a Thai citizen in 1968, and married a Thai wife. On the other hand, he is an art speculator. The smuggling of Khmer cultural relics has long been his secret, and his external identity has nothing to do with art: pharmaceutical, fitness beauty and real estate developer. This reminds me of Yuri, the arms dealer in "Lord of War". His arms business has been carried out in secret, and his external identity is a transportation practitioner. His famous saying is, "Selling arms is for peace", which is exactly the same as Reichford's "theory of cultural relics protection".

Douglas Redchford with Khmer artifacts Photo: Bloomberg

"Without arms dealers, many countries would not even be able to fight a decent war," arms dealer Yuri once vowed. This statement is also completely reasonable for Reichford. Without smugglers like him, large museums in Europe and the United States could not even build a decent "Asian Art Department", and Khmer art would not be recognized by the world as it is today. The New York Times called Reichford "a very cultured collector of Khmer sculptures and jewelry, and the quality of his collection is museum-level"; The Diplomat said that Reichford was a leader in the sale of cultural relics during the Khmer Rouge period, and his collection was rich enough to rival a country. In 2008, the Cambodian royal family awarded Reichford the Grand Medal of Artistic Contribution.

The debate between museology, collection system and property law

The emergence and development of Western museology itself is parallel to the colonial system. In the 18th and 19th centuries, with the expansion of overseas colonies, natural history and national history were born. The regional departments of large museums were built according to the colonial system, such as the Netherlands's Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, the Tropenmuseum, the Afrika Museum, the Museum of Ethnology, or the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. John Guy, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, said, "Everything in the museum must come from somewhere."

The Standing Eight-Armed Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion, which was once exhibited, was collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2002 and returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024. Photo: Washington Post

The collection system and property ownership are also dominated by the West, and complement museology. Although international law has a series of protections for the return of cultural relics, such as the 1815 Treaty of Vienna, which stipulates "the return of cultural relics obtained by war"; the UNESCO General Conference adopted the "Recommendation on Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property" in 1964, and later adopted the 1970 Convention. However, international law does not coordinate with the rules of the international art market and the principle of property ownership. When the applicable laws compete, the latter is usually more effective.

Left: Ardhanarishvara, 7th-8th century, Cambodia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024. Middle: Head of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion, mid-10th century, Cambodia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024. Right: Four-Armed Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion, early 11th century, Cambodia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024.

First, the private laws of various countries grant the right of defense to those who obtain cultural relics through the open market. For example, lawyers of Sotheby's auction house once cited this clause to defend the auction of smuggled Khmer cultural relics: "They were obtained through legal transactions and purchased at a public art fair in London under a legal contract."

Standing Female Deity, 10th century, Cambodia, collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2003, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024 Photo: MET

Secondly, the 1970 convention requires the contracting parties to return collections stolen from public institutions, but there are no provisions for stolen cultural relics from non-public institutions. Redchford took advantage of this point and claimed that his Khmer cultural relics were purchased from Thai farmers and private art dealers, not stolen from public institutions, and that the thousands of temples in Cambodia where the sculptures came from were not recognized as "public institutions" in Cambodia.

Left: Face from a Male Deity, probably Shiva, 930-60, Cambodia, collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1998, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024 Photo: MET

Right: Standing Female Deity, probably Uma, mid-11th century, Cambodia, collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1983, returned to Cambodia on July 3, 2024 Photo: MET

Thirdly, the private laws of various countries also grant the right to defend against the statute of limitations. Some collection institutions or buyers believe that the statute of limitations has expired in order to recover Khmer cultural relics that were made more than 1,000 years ago and stolen 100-200 years ago.

An expedition team traced stolen cultural relics in the Cambodian jungle. Photo: The New York Times

Finally, it is the identification of the ownership of property rights, which is also the most difficult part. The lawyer of Sotheby's auction house, which auctioned Khmer cultural relics, believes that "according to US law, the most important thing to trace property rights is to prove ownership. How can Cambodia prove that these cultural relics belong to Cambodia?" The Khmer art style is cross-border. Due to historical reasons, there are Khmer-style sculptures in Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar today. The lost cultural relics have been resold many times, and it is difficult to trace the circulation process. The true identity of many buyers is kept secret. The buyer cited the "Property Law" in the "Civil Code" to protest against the "original acquisition of property rights", that is, to define the acquisition of cultural relics as "good faith acquisition, time-limited acquisition, prior occupation, found or discovered", and regarded the Khmer statues as unclaimed lost property, which should belong to the finder.

Judicial, administrative, purchase or donation: Differences in the paths of cultural relics return in different countries

Although the return of cultural relics still faces legal and procedural disputes, in recent years countries have followed the trend of decolonization and return of cultural relics. However, the return paths of different countries are not exactly the same.

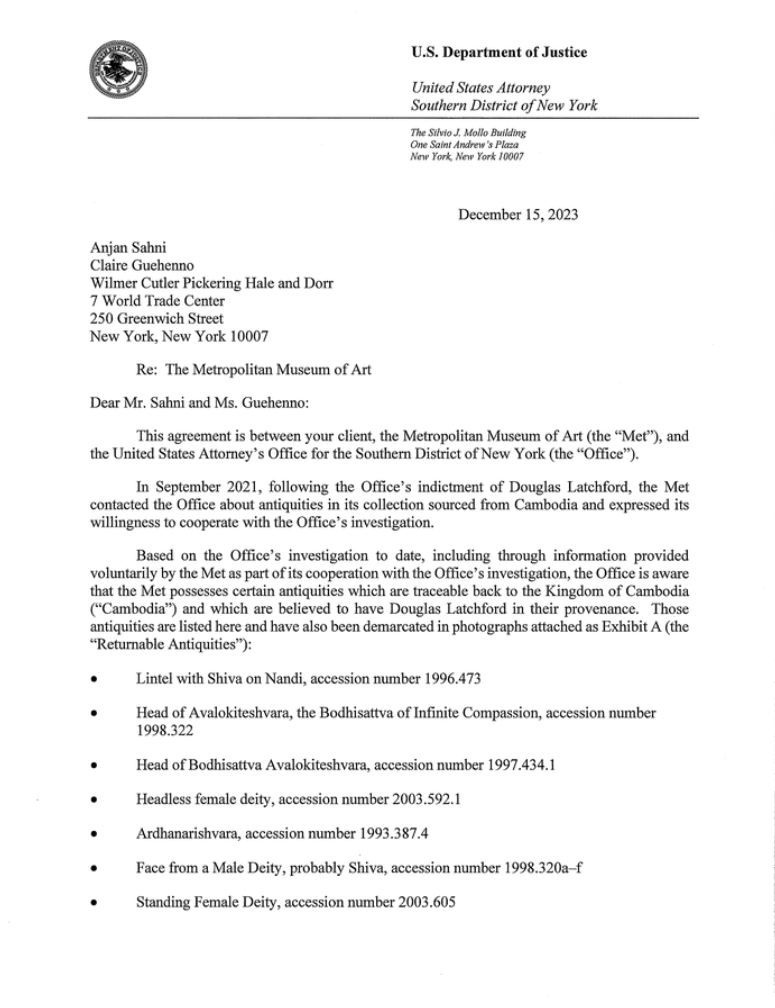

The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the U.S. Department of Justice reached an agreement on the return of Cambodian cultural relics. Photo: ICIJ

The United States has recovered cultural relics through judicial and journalistic investigations. In the return of Cambodian cultural relics, the New York Attorney General's Office, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Justice played an important role, and through social forces such as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, they traced the origins of cultural relics, collected evidence, and recovered cultural relics through multiple judicial procedures such as investigation and prosecution.

"Dahomey" documentary about French return of African cultural relics

France returns cultural relics through administrative means such as government and presidential commissions. In 2017, during his state visit to Africa, French President Macron proposed returning cultural relics to Africa within the next five years. He then commissioned art historians and economists to conduct an investigation report on public museums in France and disclosed to the public the colonial history of the looting and theft of these cultural relics, so that the public can understand France's colonial history.

Britain returns Angkor Wat royal jewels to Cambodia: The Times

German public museums tend to take an evasive attitude. "German public museums are reluctant to make their collections public. They will systematically hide them, especially those acquired through scientific expeditions and smuggled cultural relics in the early years, for fear of attracting claims from other countries. But the French public service department will consider it its obligation to disclose all information to the public," French art historian Benedict Savoy concluded.

The return of Chinese cultural relics is achieved through cooperation with foreign governments, charitable donations and judicial means. For example, the French luxury giant, the Pinault family of Kering Group, donated the rat-headed and rabbit-headed bronze statues of the Old Summer Palace, the body of the Shang Dynasty bronze dish square jar, and the early Qin Dynasty gold ornaments from Dabaozi Mountain in Li County, Gansu Province to China by way of free donations to my country or by facilitating agreements between Chinese museums and foreign auction houses. In 2022, the Fujian Provincial High People's Court made a ruling on the first case in which a Chinese non-governmental organization sued in China to recover cultural relics lost overseas - the "Zhanggong Zushi Statue" case, safeguarding the rights and interests of the countries of origin of cultural relics through judicial means.

Smuggled Khmer artifacts pursued by the U.S. Attorney's Office in New York Photo: Phnom Penh Post

In 2020, when the U.S. prosecutors were investigating the case of the smuggling of cultural relics by Reichford, Reichford died of natural causes and was exempted from legal responsibility. He made countless fortunes with Khmer cultural relics and was also a scholar and promoter of Khmer art. When he dug out Khmer stone sculptures from the remote jungles of Cambodia and pushed them to the world for people to see, he also dug a grave for himself, covering it with lawsuits, crimes and infamy. Today, cultural relic theft is still happening around the world, and the circulation of smuggled cultural relics is a market with an average annual scale of 10 billion US dollars. Reichford and others showed the world what heaven looks like, but also opened Pandora's box and the door to hell.