Although many Western classic paintings have been exhibited in China, for most people, appreciating Western works of art is actually more through a screen. It is difficult to see the original work, let alone the frame. However, the frame is actually very beautiful. Important because it tells a story about the role of a work (painting or sculpture, etc.) at that time.

Alison Wright, a professor in the Department of Art History at University College London, specializes in the study of Italian art from 1300 to 1550. She is the proposer of the frame theory, an important theory in current Renaissance studies. This theory holds that frames and framing devices were central to the workings of Renaissance imagery, and that during a period of rapid cultural change, frames began to ensure an independent concept of "artwork"; and that resetting the frame could adjust the meaning of the work of art.

Recently, Alison Wright accepted an exclusive interview with The Paper in Shanghai. She believes that Western painting theory is closely related to the larger framework theory, which is not only derived from art history, but also rooted in literary theory and communication theory.

Alison Wright, professor of the Department of Art History at University College London, delivered a public lecture in Shanghai entitled "Elevation and Sacred Space in Renaissance Altarpiece Decoration".

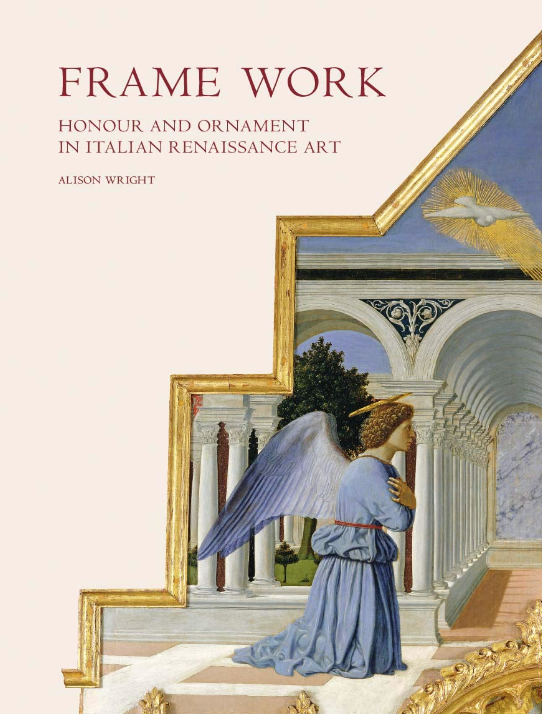

Alison Wright, as one of the scholars in China who participated in the "Dialogue between Outstanding Scholars in World Art History: Art and Culture in the Renaissance" launched by the World Art History Institute (WAI) of Shanghai International Studies University, gave a speech in Shanghai This is a public lecture on "Elevation and Sacred Space in Renaissance Altar Decoration". The content of the lecture is derived from his 2019 book "The Frame Work: Glory and Decoration in Italian Renaissance Art", which explores the Italian How "ornament" in Renaissance paintings and sculptures (including the physical frame and base itself and the fictitious architectural elements and other auxiliary elements inside the work) embodies and affects social relations and meanings.

"The Frame: Glory and Decoration in Italian Renaissance Art" by Alison Wright, published by Yale University Press in 2019

During her stay in China, Alison Wright also gave a lecture titled "The Golden Chapel of San Zaccaria: The Space and Era of Venetian Gold" at Peking University; she also held a lecture on "Gold: Special and Era" at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. Difference” workshop, which is related to her ongoing work on a book tentatively titled Gilded Cities: The Politics and Performance of Gold in Europe, 1350-1550 AD.

This exclusive interview also revolves around frame theory and gold research, mentioning the relationship between the works of Van Eyck, Donatello, and Raphael and picture frames, and extending to the mounting of Chinese paintings and the entanglement between East Asian and European visual cultures. , as well as Chinese prehistoric bronze casting and Italian Renaissance bronze sculpture.

About frame theory

The Paper: As the “proponent of frame theory,” how did you first pay attention to this theory?

Wright: As a PhD student, I attended a workshop on the chapel of San Miniato al Monte in Florence, which was built for the Portuguese prince and cardinal James (who built it in 1459). Died in exile in Florence, construction of the church began in 1462 (an inscription on the wall shows that the church was completed in late 1466), and its architect was Antonio Manetti.

On the hill near Piazzale Michelangelo in Florence is the Chapel of San Miniato Almonte, a small Romanesque church.

During an on-site inspection of this chapel, I found that the frame in the middle of the altarpiece was embedded in the wall and related to the adjacent building components. The world in the frame is not just a painting, but a sacred space. The original altarpiece is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is believed to be a work jointly created by Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Piero del Pollaiuolo. There are three saints painted on the painting. It's truly a revelation when you're around it and watching it.

Altarpiece of the Portuguese Cardinal, frescoed curtain on the wall around the altar (copy of the painting, original in the Uffizi Gallery), 1460-1473, San Miniato Almonte, Florence chapel

To the right of the altarpiece, the tomb of the Portuguese cardinal

To the right of the altar is the Cardinal's tomb, with a marble statue by Antonio Rossellino on one wall. Two angels above it open the curtain, and the frame becomes a kind of portal to the world, expanding the world of the church. And the church itself is filled with nested frames of arches - frames around the paintings, then frames around the walls, then the vaulted frames of the church. From this, the study of picture frames and frames began to enter my field of vision.

Altarpiece and tomb of the Portuguese Cardinal in the Chapel of San Miniato Almonte.

The Paper: What role did decorative frames play in works of art during the Renaissance? How are they designed and used to highlight the thematic and aesthetic features of the work?

Wright: Frames have many different roles. One of the most familiar phenomena is the use of frames to give the viewer the impression of an independent painting, and the frame no longer fixes the works in a certain location, allowing them to be moved from one place to another for collection.

For example, the British National Gallery collects a portrait (considered a self-portrait) by the Northern Renaissance painter Jan van Eyck. The frame is engraved with a line of inscriptions - "as I can." All you can)” This is like a pun. "Johannes de Eyck me facit (Jan van Eyck made me)" is written at the bottom of the frame. Sometimes this approach suggests that the painting itself is a representation, with the frame as if van Eyck himself is seen through a window.

Van Eyck, Portrait of a Man (or Self-Portrait), 1433, 26 x 19 cm, National Gallery Collection

However, I work more on frameworks that must be fixed. For example, walking into a church and seeing the frame of the tabernacle. The function of the frame is to tell believers that this is a gift from heaven and is for worship. You will find a number of arches, pediments and nesting frames placed around the shrine to indicate that this is the abode of God. Without these, it would be almost impossible to identify the Eucharist as just a piece of bread (note: the body of Jesus turned into bread), and the study of these elements is part of the framework theory.

Mina da Fiesole (1429-1484), Tabernacle of the Blessed Sacrament, circa 1473, Santa Croce, Florence

In Italy, the frame may be of angels under arches carrying inscriptions towards doorways. Many people are interested in the frames of images of the Virgin Mary, which performed miracles. The frame is also a way to pay homage to the person in the painting or the portrait itself. The frames of the altars were beautiful and intricate, and they were thought to provide beautiful dwellings for the gods.

There is also an example of the Annunciation, a relief sculpture by Donatello in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence. It has a huge frame, thick and complex in structure, reproducing ancient patterns in a very creative way. This frame has, I think, very strong aesthetic features, but it is the shrine and the theological reasons for its existence are much more important.

Donatello (1386-1466), Annunciation, circa 1433-1435, located in the sixth bay of the south aisle of the Cathedral of Santa Croce in Florence

The Paper: In early May, the original 19th-century Gothic frame of Jan van Eyck's "Arnolfini Double Portrait" at the British National Gallery was replaced by a 15th-century gilded frame. This replacement caused a stir. Polarized reaction, what do you think of this replacement? [ Note: Peter Schade, head of the National Gallery's framing department, said, "Without the competition of incongruous engravings, the figures appear larger and the details are clearer"]

Wright: Because this happened so recently, I haven't seen it in person in its new frame. I saw reports and was very concerned about the fact that "Arnolfini Double Portrait" was given a new, but older, frame. This was a very brave move. "Arnolfini Double Portrait" is one of the most famous paintings in the British National Gallery and one of the most important Dutch paintings. However, it is small in size and often confuses those who see it for the first time. The viewer is surprised.

The "Double Portrait of Arnolfini" with a new frame on display at the British National Gallery, on the left is Van Eyck's "Portrait of a Man (or Self-Portrait)"

Actually, what interests me is the old picture frame, which is a dark wooden picture frame from the 19th century that looks a bit Gothic. Make the viewer feel that this is a medieval work. Now Peter Schad, head of the National Gallery's framing department, has tweaked a golden frame that is almost certainly from 15th-century Italy. The current frame makes the painting feel more forward-looking, even though it is an older frame.

Peter Schade compared the old and new frames on his social media, and thought that the new "figures look larger, the details are clearer, and there is no interference from incongruous sculptures."

I have two concerns about this change. First, why would you want to replace the original 19th century frame? I think the original one is beautiful. Although it may not be perfect, it does not hinder the display of the painting. Moreover, it has been presented in this way for such a long time. The frame has become an important part of the painting's history. I think for such an important work, you have to be very sure that it will really fit before you decide to replace the frame, because you are changing the history of the National Gallery.

Van Eyck, "Double Portrait of Arnolfini", 1434, 82×60 cm

Another concern was that the new frame used was a dull, dull gold frame. This is very similar to the frame that van Eyck might have used for a small portrait, and indeed the same frame for his self-portrait in the National Gallery that I mentioned earlier. So when I saw the new frame I felt like the rather grandiose status of the painting had changed visually, the old frame looked like a threshold and it gave the impression of looking into a room and at the end of the room there was A mirror with a huge frame.

Van Eyck, "Double Portrait of Arnolfini" (detail)

So the whole idea of the painting is to make the viewer feel like they are entering someone's room. In fact, if you look in the mirror, you will see someone standing in the doorway, as if they just walked in. So this painting is trying to create a sense of people entering the home of this wealthy couple and being welcomed, and there's the dog that's greeting them. This is not only an intimate painting, but also has a considerable sense of ritual.

Van Eyck, "Double Portrait of Arnolfini" (detail)

But in the new frame, the characters look smaller and the sense of space is different. It looks like you enter the room through a window rather than a door. I guess I need to get used to the new frame, I prefer the feel that the previous frame conveyed even though it might not be exactly right. There is a solemn air to this painting, which is well reflected in the frame that precedes it. Peter Schad is a very good frame builder and he might understand how I feel.

The Paper: The decoration of buildings and public spaces is also included in the category of frames, such as Baroque works and picture frames, Baroque sculptures and architectural construction. What is the relationship and boundary between paintings and frames?

Wright: I think this question can be divided into two parts. First, during the Renaissance, painting frames were often embedded in larger frames (such as domestic settings), and many paintings were hung high on the walls above furniture (such as the Madonna and Child). Therefore, paintings are not just independent decorative objects, but part of the overall decoration. Especially in churches, there are often many altarpieces in one church, so the frames of these paintings often compete with each other. The frame patron must consider both the type of painting he or she wants to commission and where it will be placed. Therefore, the frame of the altarpiece would be interconnected with other decorations in the church, such as architectural frames or paintings on the walls. The frame must intervene in an already existing space and transform it.

Interior view of Holy Spirit Church in Florence

What I found in my research was that some interesting phenomena that happened during the Renaissance developed in the architecture of certain churches in an attempt to bring some order to the space of this frame. For example, Filippo Brunelleschi's Basilica di Santo Spirito (Florence), which is a church with many columned arches, all the paintings have the same type of frame, you You will see a heavenly order in it, and anything hanging here will look out of place. I think this is an important aspect of the relationship between painting and frame, especially for religious art.

Giovanni Bellini (c. 1435-1516), Altarpiece of St. Job, circa 1480, original work in the Accademia Gallery, Venice

For much secular art, the role of the frame may be slightly less, since the frame is often replaced. When you redecorate a room, you might want to give a painting you own an updated frame.

So, what is the boundary between painting theory and frame theory? This is difficult to answer because I am not just focusing on painting, but also on the theory of frames in relation to painting, which has become a specialized area of discussion since the 20th century. For example, Meyer Schapiro (Lithuanian American art historian, 1904-1996) talked about the role of the frame, arguing that without the frame, the painting would feel like a part of the world, but with the frame, It seems to say, "Look at a different world here." This is a typical frame theory. Others, like Georg Simmel (German sociologist and philosopher, 1858-1918), simply regarded it as a boundary to allow the viewer to focus on the picture. There are also some scholars, such as Louis Marin (French philosopher, historian, semiotician and art critic, 1931-1992), who believe that the picture frame is a place of expression. Inviting you to think, especially in paintings from the 16th century, you will see a lot of frame-within-frame phenomena, forming a self-aware painterly expression.

Pierre-Hubert Subleyras (1699-1749), Studio, 1740s, 125 x 99 cm, Collection of the Academy of Plastic Arts, Vienna

For example, a work depicting flowers in a niche is flat in itself but appears to have a frame and a frame outside the work. This effect of Renaissance painting became a personal study of mine interest. In illustrated manuscripts of books, images can also be seen juxtaposed with text and take on the appearance of framed paintings. These illustrations are often very intricate with landscapes or other elements. This theory of painting is closely related to a larger theory of frameworks, derived not only from art history but also rooted in literary theory and communication theory.

The Paper: The framework is mostly considered to be a study of the social background in which the work is located. Will this kind of research in turn affect the judgment of the work itself? In cross-cultural research, how does framing theory help us understand the differences and commonalities between cultures?

Wright: I think the impact, as we discussed before, is that the content of the work can be understood through the framework within which it is placed. The examples I gave earlier also illustrate why I think frames have a powerful influence on the evaluation of artworks.

For example, Jan van Eyck knew that if he wrote "Jan van Eyck made me" on the frame of a picture, people would think it was by a great painter and that the person in the picture was the subject of the painting. This is very clever. So, it's both the subject and the artist that does influence how future generations evaluate the artwork.

The same example of Van Eyck mentioned earlier, the original slightly Gothic frame of "Arnolfini Double Portrait" from the 19th century makes people feel that this is an older painting than reality. Yet we often overlook picture frames, and people rarely talk about them when doing art historical research. When we look at paintings now, we often see them on a screen. In many cases we have never seen the original painting, or even know what the frame looks like. However, in the study of art history with social and political overtones, the frame is very important. Because the frame tells you a lot about the role of a piece of painting or sculpture at that time.

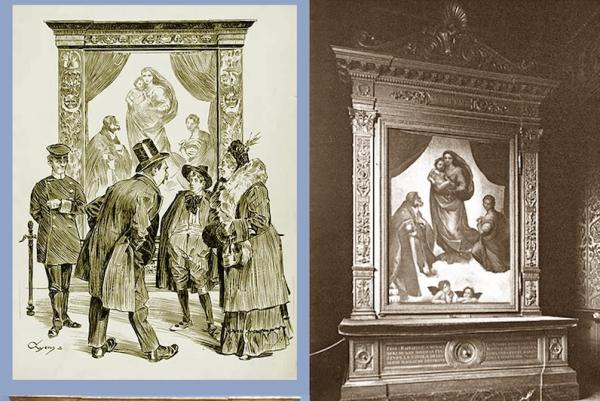

Of course, changing the frame every time (which is particularly common in museums, especially around exhibitions) changes people's evaluation of the painting to some extent. An example we often mention is Raphael's painting "The Sistine Madonna" collected by the Master Gallery in Dresden. This painting has had three to four different frames, and each change conveys a different message. information.

Raphael, Sistine Madonna, 1512-1513, 265 x 196cm, Old Masters Gallery, Dresden;

Left: Caricature by Hans Gyenis (1873-1926), published on January 13, 1908. Right: Photograph from the 1920s, both showing the painting being produced in the 1850s in the frame.

Originally, it had a Dresden style frame, wanting to highlight that the painting was from the Dresden collection. Later, it was replaced with a cassette frame that looked more like a window frame. Recently it was remounted in a frame that makes it look like an altarpiece, when in fact it was originally painted as one.

After World War II and a trip to Russia, the Sistine Madonna was mounted in encrusted gilt and blue lacquered frames; the most recent frame, right, was produced in 2012.

But this frame is not from the Renaissance, but from the 21st century. Sometimes I even wonder if some people might consider this a Renaissance box? The Dresden Masters Gallery wants the audience to not only think that this is a masterpiece by Raphael, but also to realize that it was once an altarpiece and had a specific social function.

Wang Lianming, associate professor at City University of Hong Kong, mentioned three cases in his speech.

The Paper: Associate Professor Wang Lianming of City University of Hong Kong mentioned in your presiding speech that “the picture frame as a conceptual category presupposing its function as a contact point or boundary between cultures, traditions or artistic practices is extremely important. The Earth has enriched readings of art history in recent decades,” he said, referring to East Asia and its entanglements with European visual culture. What do you think of this entanglement? [ Note: The original text of Wang Lianming's statement reads "When paintings from the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) arrived in Japan, they were cut into small pieces and remounted with brocade to suit the viewing habits of Japanese generals' tearooms. In the 18th century In the Qing court, when the emperor collected a Neolithic jade jade, it was incorporated into a miniature rosewood screen, effectively 'recreating' an artifact from an unknown historical period. Likewise, when Chinese blue and white porcelain was collected and used in early times. The metal frame has become a necessary device when displaying modern Europe, or as Monica Juneja of the University of Heidelberg puts it, 'it reinforces the perception of agency-based cross-cultural connections in the study of circulation or the disengagement of flows. often lost in environmental studies '"]

Wright: Lian Ming made a very good point, which is that when these works are collected, they are often marked (framed) as someone's collection, and it will be recorded. Western Europe and China have this tradition. I think China Earlier, because China has long had the practice of gathering collections together, and collectors always want to do something special with their collections.

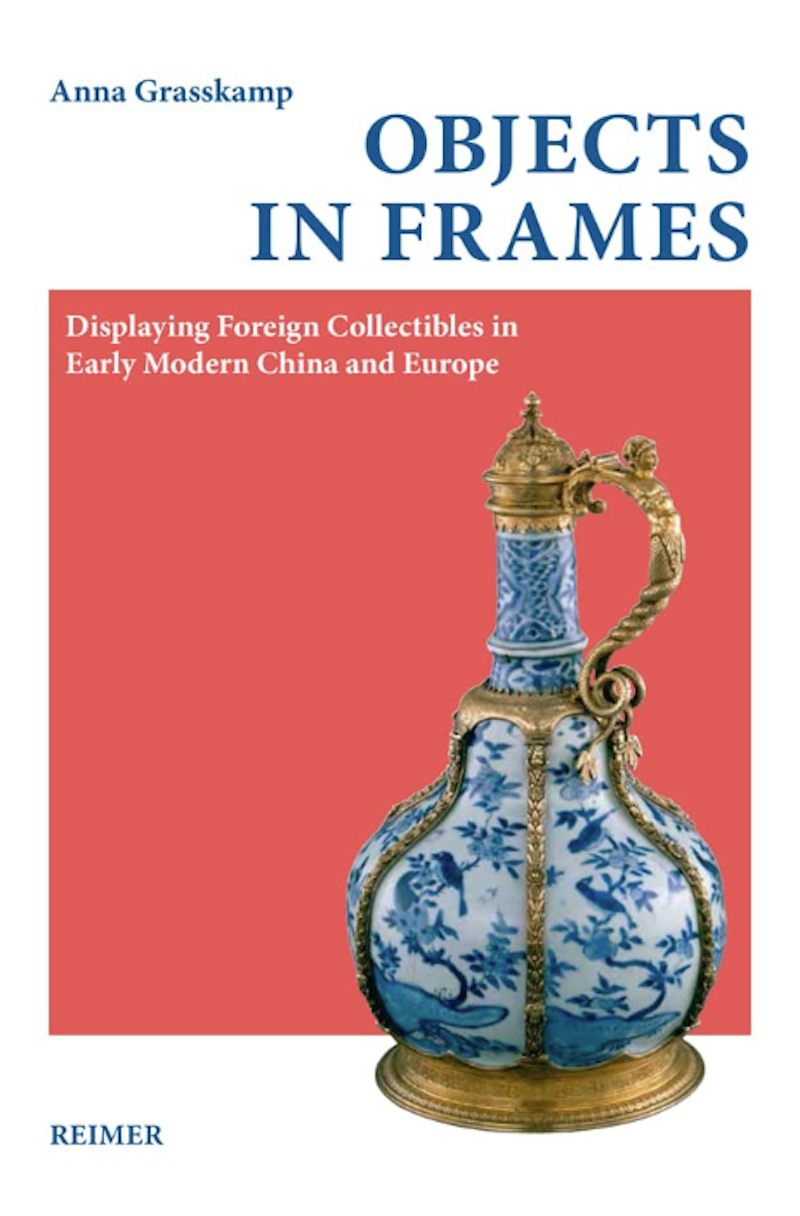

Wang Lianming cited the example of "when Chinese blue and white porcelain was displayed in early modern Europe, metal frames became a necessary device" - a Chinese vase "framed" into a German hip flask

What is particularly interesting is that in the research of Anna Grasskamp (University of Oslo), we can see that when the Chinese porcelain vase entered the art market, it was both a commodity and an exotic object. artwork. "Framing" a Chinese vase into a German hip flask has separated it from its original culture and appropriated it in a Western cultural context. This is to a certain extent a political act that makes this object Become understandable within a new “framework”. This frame is a Western perspective and also shows a desire to tame the object to one's own will and understanding.

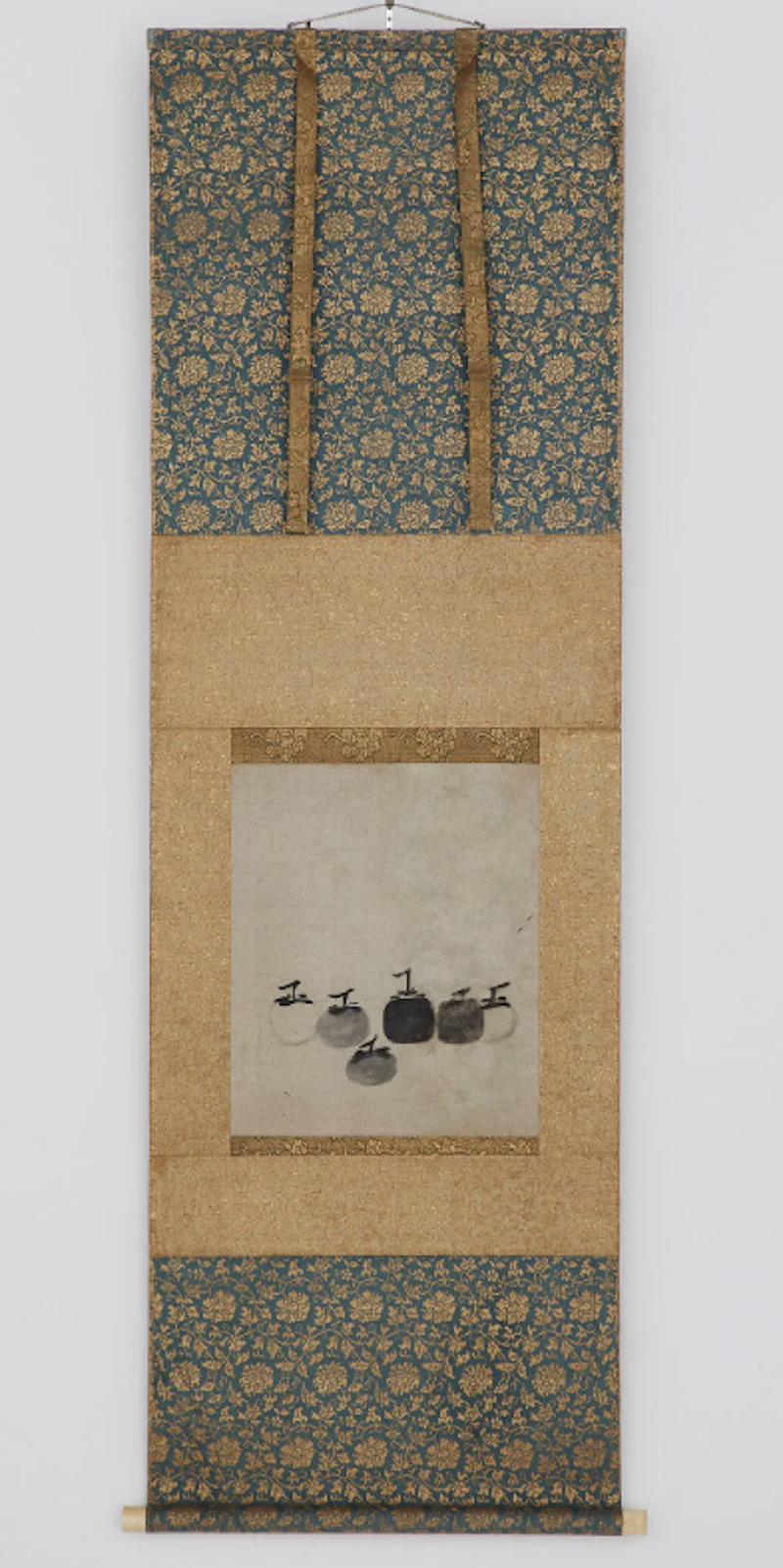

Mu Xi, "Six Persimmons", 13th century, collected by Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto, Japan

I think the 18th century was a time of globalization of collecting, when people used collections to name and classify objects. "Framing" has become more and more important, and all collectors, whether in Beijing or London, tend to re-frame the original scrolls, but cutting the original long scrolls and re-framing them is a rather violent act. Jacques Derrida (Jacques Derrida, one of the most important and controversial contemporary philosophers, 1930-2004) believed that this is a violent cutting. After the Chinese scroll painting is cut, it is no longer a story or story. It becomes part of a larger viewing process and becomes something you have to pay attention to.

The scroll "Admonitions to Women's History" collected by the British Museum is divided into three parts and displayed flat.

Framing, to some extent, determines how we see and understand a work of art. Through the choice of frames and the way they are framed, objects acquire new meanings and interpretations in new cultural and social contexts. Or it can be understood that when these items from China were brought to Europe, they were mainly appreciated as assets that could increase in value rather than being used as practical containers. In order to localize the functions of these items, traders usually added Decorate them with gold or other metals in order to give these items some purpose so that they can be admired as works of art as well as used daily.

Research on gold

The Paper: Your current research involves the changing aesthetics and material economy of gold in Renaissance art. What do you think of the widespread use of gold in Renaissance art?

Wright: I think the widespread use of gold in Renaissance art deserves special attention. Renaissance art is often compared to medieval art, which featured golden surfaces, golden frames, and golden utensils. In contrast, the use of gold in Renaissance art was not emphasized. But in fact, gold painting was still heavily used in Renaissance art, especially in the early 15th century, and in some areas of Italy until the early 16th century. However, this was not always recognised, as these works were often considered to be somewhat outdated and inconsistent with the latest aesthetic tastes of the time.

Spinello Aretino, Niccolò di Pietro, Lorenzo di Niccolò, Altarpiece of Santa Felicita , 1401, painted in the church of Santa Felicata in Florence, now in the Accademia di Florence

The main reason for this is that the history of Renaissance art is mostly written from a Florentine perspective, and Florence stopped using a lot of gold decoration on paintings earlier than other regions (although gilded frames were still used), but in early Renaissance Venice , Milan or Naples, and even Spain largely continued the use of gold in medieval art.

The works "Melchizedek King of Salem" and "Aaron the High Priest" by the Spanish painter Juan de Juanes (approximately 1510-1579) are collected by the Prado Museum and are currently on display in Shanghai.

Why is gold so difficult to abandon completely? One reason for this is the large amount of religious art that dominated the Renaissance. Gold was a way to show the preciousness of the subject matter and could symbolize heaven. Painters used gold to indicate sanctity. Painters such as Van Eyck used yellow and brown to simulate gold, while Venetian painters directly gilded the surface of their works to make belts and other decorations appear three-dimensional and textured. Even some Venetian altarpieces have very few actual painted parts, and the golden frames and golden decorations on the figures are eye-catching enough.

"Golden Chapel" in San Zaccaria, Venice

During the Renaissance, painters were also sculptors or goldsmiths. Gold is used not only for its own value, but also because it attracts the attention of the viewer and marks the excellence of what you are seeing. This is why the halos of the saints in the painting are made of gold, indicating that these figures possess extraordinary virtues and heavenly glory.

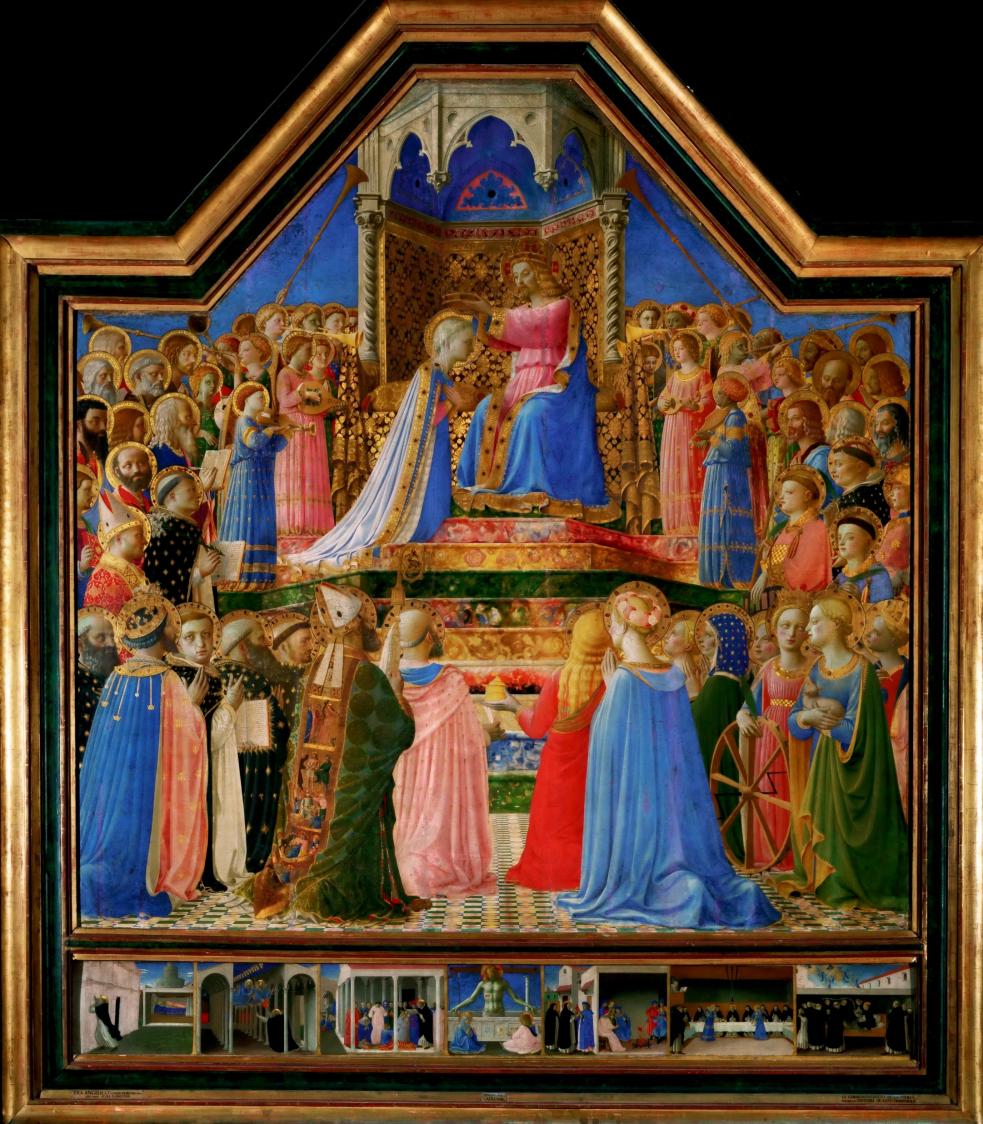

Fra Angelica, Coronation of the Virgin, circa 1432-1434, tempera on panel, 209x206cm, Louvre Museum, Paris

In addition, for patrons, they like to show off the gold they can afford, but the actual gold foil used seems expensive, but the cost is not high. A small piece of gold leaf can cover a large area, creating a massive golden effect. Thus, another attraction for gold's continued use in Renaissance art was its efficiency and relatively low cost.

The Paper: What is the relationship between gold aesthetics and artistic creation?

Wright: I would like to give you two examples of this. One is a sculpture. I have written quite a bit about fully gilded bronze sculptures. This is a professional sculpting technique used since ancient times, and as can be seen, sculptures made of copper alloy look very gorgeous. In 15th-century Florence, Donatello (1386-1466) was one of the first artists to make sculptures entirely gilded. In the niche on the front of the Orsanmichele Church in Florence, there is a statue of the saint called Saint Louis of Toulouse, which is fully gilded. It reflects the light and looks special, glowing with its virtues. Secular people acquire the appearance of another world. In addition, many late medieval British tombs were completely gilded to indicate that the tomb was a monarch, with the idea that the person in the tomb would ascend to heaven.

Donatello, Saint Louis of Toulouse, 1423–1425, gilt bronze

At the same time, the artist must focus on the engraving technique of gold. In other words, to apply gold leaf, you have to polish it, which takes a long time and may be done with an assistant. And some auxiliary tools will also be used. For example, with a metallic pen, you might make some indentations on the gold foil, or even draw an angel with tiny dots of the metallic pen. But if gold foil is used on a large area, the studio needs to be very clean and free of dust, otherwise it will stick to it. Therefore, painting with metal is very time-consuming, because while working, you have to keep the environment clean and tidy.

"The Annunciation and St. Margaret and St. Anxano" by the Italian painters Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi of Siena, 1333, tempera gold foil altar Painting, Uffizi Collection

Detail of the Archangel Gabriel in the Annunciation and St. Margaret and St. Anxano, showing the use of gold leaf and metal pen

The Paper: Gold has been endowed with special meanings in Chinese and European cultures since ancient times, including China’s prehistoric Sanxingdui (Note: Wright visited the Sanxingdui Exhibition and Bronze Exhibition Hall of the East Hall of the Shanghai Botanical Garden). Gold has played a role in the circulation of global art. What kind of role?

Wright: I would love to share my experience of visiting the Shanghai Museum, but my understanding may be from a very typical Western perspective, and may be very banal. Through the exhibition, I learned that everything I saw was at least 500 to 600 years earlier than I expected, especially in terms of bronze casting technology, which was amazing in the 11th century BC. I think this is a thought that many people may have. But I learned something valuable—observing the development of the use of a particular material in a single culture over a long period of time is a wonderful way to study art history.

The bronze ware (partial) on display at the Shanghai Museum discusses the casting method based on the patterns and seams on it.

The use of bronze and gold I saw in the Shanghai Museum was different from Donatello's. For bronzes, you may be able to observe them from multiple angles and check out their internal structures, texts, etc. Moreover, bronze chimes can also make beautiful sounds. The beautiful sounds made by the chimes in the background of the exhibition resonated with me. This characteristic has been highly valued in Chinese culture for a long time.

Alison Wright visits the Shanghai Museum (People's Square Branch).

I think the exhibition does not have too many textual annotations, and the cultural relics speak for themselves, which is very good. I find it amazing that, thanks to these bronze artifacts, we now have access to a culture that was still relatively unknown, where much of the writing that took place on the bronzes survives today as a historical document.

There are some great examples in the Sanxingdui exhibition, gold foil masks, birds on the bronze sacred tree... I don't know how to describe these, I am also fascinated by them. We are not always sure of their purpose, but they were associated with altars, and the faces of these figures were covered with gold ornaments, which enabled them to communicate with heaven.

Gold masks on display in the Sanxingdui exhibition at the Shanghai Museum

Compared with the bronze craftsmanship of the Renaissance a thousand years later, Chinese bronze is extremely exquisite. In contrast, Donatello's David, one of the most famous sculptures in the world, was poorly cast. After removing it from the mold, it takes a lot of time to carve and trim it. [ Wang Lianming’s note: China’s lost-wax method is actually very controversial. The lost-wax method should be relatively certain to have appeared in northern China in the 2nd-3rd century, but new research suggests that it appeared earlier. 9 See Peng Peng, Metalworking in Bronze Age China: The Lost-Wax Process (Cambria Press, 2020). Therefore, Sanxingdui could not have been cast by the lost wax method, but was cast by Tao Fan. It is first hand-made with clay and has a hollow center. Some large bronze shapes need to be made from two or more pottery molds, which is called a combined mold. ]

Donatello's bronze sculpture "David"

Note: Wang Lianming is an associate professor in the Department of Chinese and History at City University of Hong Kong. We would like to thank him, Lu Jia (PhD candidate at WAI), and Shanghai International Studies University World Art History Institute (WAI) for their great assistance in this article. The "Lectures for Outstanding Scholars in World Art History" will be launched in September 2023. The theme of 2023-2024 is "Art and Culture of the Renaissance". 12 first-class scholars from six countries will be invited to China to share research in this field. Results.