His research spans various eras, from early Baroque architects such as Giuliano Finelli (1602-1653) and Bernini (1598-1680) to mid-period figures like Botticelli (1445-1510) and the latest, Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770). How do we truly connect these artists through research?

Recently, Dombrowski gave an exclusive interview in Shanghai to The Paper Arts, where he expressed, “Creation” is a contribution to the world—“the art I understand is autonomous, revealing the free spirit,” and “the misunderstanding of the Renaissance master Botticelli largely stems from Vasari.”

After delivering a lecture titled “The Love of Wisdom: Botticelli’s St. Augustine and the Invention of Modern Sanctity” at the Shanghai Duolun Modern Art Museum, Damian Dombrowski interacts with the public.

Damian Dombrowski is a professor of art history at Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg and serves as the director of the Martin von Wagner Museum (Painting and Print Department) at the university. This museum houses the third-largest university art collection in the world. His research encompasses a wide range of subjects within Western art history, including Carolingian book illustrations; medieval funeral art; painting and art theory from the Florentine Renaissance, especially studies on Botticelli; visual arts, architecture, and urbanization during the German Renaissance; Baroque sculpture in Rome, Naples, and Spain, particularly studies of Bernini; Neapolitan painting in the 17th century; studies of Giambattista Tiepolo; research on Martin von Wagner; studies of Paul Cézanne; and 20th-century Italian painting (notably Giorgio de Chirico’s work), along with American painting from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

As one of the scholars invited to China for the series “Conversations with World-Class Scholars on Art and Culture of the Renaissance,” initiated by the World Art History Institute (WAI) at Shanghai International Studies University, Dombrowski recently delivered three public lectures on Botticelli and Tiepolo in Shanghai and Beijing, along with a summer seminar in Hangzhou on “Classicism in the Renaissance.”

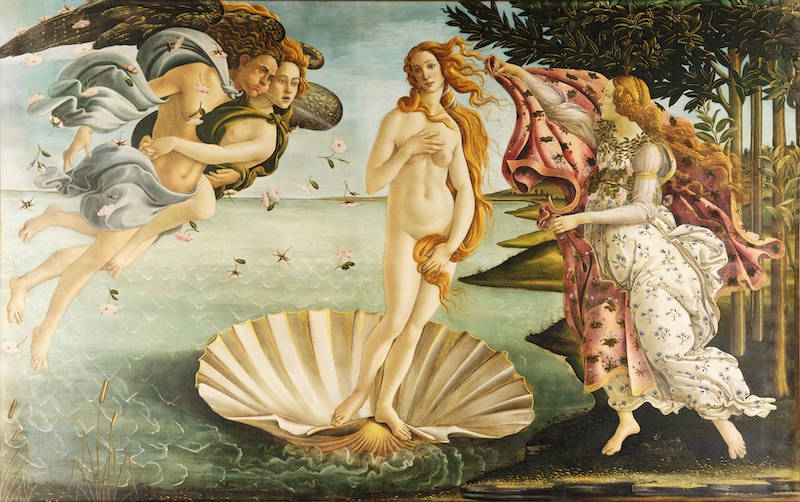

On a summer night in Shanghai, Damian Dombrowski delivered a public lecture titled “Love Descends Upon the World, and Art Returns to Its Essence: Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and the Origins of Modern Aesthetics” at the Liu Haisu Art Museum.

As early as 2008, Dombrowski proposed a vision for “Comparative Art Studies,” but it wasn’t until 2024, when he came to China, that he truly recognized the similarities and differences between China and Western Europe, realizing that “Comparative Art is only just beginning.” He anticipates that his next research project will focus on “Tiepolo and Ancient Chinese Art” or “Tiepolo in the East,” and if possible, he hopes to “initiate a dialogue between Tiepolo's drawings and Chinese artworks to pursue the rhythm of the world—this will be an exhibition dream that is both educational and poetic.”

On Research in Art History: Creation as an Unfolding of the Free Spirit

The Paper: Your published works include those on Botticelli (1445-1510), Giuliano Finelli (1602-1653), Bernini (1598-1680), and Tiepolo (1696-1770). You are an authority on these studies; do you find any connections among these artists in your research?

Dombrowski: There is indeed a research thread connecting these artists. To be honest, I have studied many more artists across different eras, exploring from the early medieval Carolingian period (Note: The Carolingian Renaissance occurred in the late 8th to 9th century under Charlemagne and his successors, a revival of arts and sciences in Europe, known as "the first awakening of Europe.") to the 20th century. These artists are certainly included, and I have conducted specialized studies specifically about them.

However, there is no connection among them in terms of style or ideology. Artistically, I have always sought the unfolding of the free spirit, which is what I call “creation.” “Creation” is an act of contributing something to the world that nature itself cannot produce; it’s a contribution to the world.

Many art historians view art as a mirror of the world, as if art merely reflects the world. But I always begin by closely examining works of art, then I try to broaden my perspective—first, I attempt to understand the artwork itself, as it represents the artist’s contribution to the world. Of course, art reflects the state of the world, and there may be political or religious didactic purposes, but that’s not the whole story. I am more interested in the meaning of the artwork itself to the artist. This is my very personal viewpoint on how to perceive art.

Würzburg Palace, view of the stairwell ceiling, with the fresco “The Allegory of the Planets and Continents” created by Tiepolo, 1752/1753.

Honestly, I am interested in the creative spirit reflected in each work, which is why I study these works. For instance, Tiepolo's enormous fresco at the Würzburg Palace is, for me, one of the most perfect artworks. I believe it is one of the most complete realizations of the artist's vision of the world. So too with Botticelli's Birth of Venus; it truly showcases what the artist wanted to express, rather than being merely a tool for other interests.

Botticelli, Birth of Venus, circa 1485-1487, Collection of the Uffizi Gallery.

In my view, works aimed at public propaganda mostly do not count as art; propaganda serves other purposes. The art I understand is autonomous and reveals the free spirit, which is nearly the exact opposite of propaganda or so-called “propaganda art.”

The Paper: Your research covers Renaissance and Baroque art, as well as painting and sculpture. What is the relationship between Renaissance and Baroque art? During this period, there were also many multidisciplinary artists. You edited the book “Architecture and Figures: The Interaction of the Arts,” what is this interaction about?

Dombrowski: Painting, sculpture, and architecture are the three main art forms considered when discussing art history, and they interacted in a special way during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Although this interaction was not very prevalent in the early Renaissance, from the 16th century onward, the relationships between different art forms became quite close. This means that the boundaries between different types (mainly between sculpture and painting, as well as between painting and architecture) became increasingly blurred; Würzburg Palace may be one of the most prominent examples of this phenomenon.

Würzburg Palace, view of the stairwell ceiling (south side), with the fresco created by Tiepolo, 1752/1753.

After the 16th century, a so-called art system began to take shape. This means that there were art theories, the establishment of academies, and artists felt a sense of belonging; it also meant that being an artist was no longer solely about serving the church or society, but instead, as part of society, gaining autonomy. This autonomy was very clearly embodied in the Italian painter Giotto (c. 1267-1337) during the Renaissance.

Giotto, Kiss of Judas, 1304-1306, Scrovegni Chapel, Italy.

Giotto was the first artist after the post-classical period and the Middle Ages to receive praise from poets, not just in Italy, but he received commissions from various parts of Europe. He had a unique style, and the concept of style developed during this period, which we refer to as the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

The art historian Theodor Hetzer (1890-1946), who was quite influential for a time, viewed the period from Giotto to Tiepolo as a unified whole. Though there is tremendous complexity and diversity within this period, in some respects, this view is very accurate because this period is clearly distinct from the ones before and after it. Afterward, we enter the “Neoclassical” period (the main movement in European art and architecture from the late 18th century to the early 19th century), which marks the first modern Enlightenment; preceding that, the late Middle Ages were very different from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The awakening of the artist's self-consciousness is the most important feature of the period we discuss (from Giotto to Tiepolo).

Tiepolo, The Sacrifice of Iphigenia, 1757, located at Villa Valmarana ai Nani near Vicenza, Italy.

The interaction and connection between different art forms has always existed. In the Gothic period, there were also intertwined decoration of painting, sculpture, and architecture in churches, but this desire for integration became clearer starting from the Renaissance. Thus, from the Renaissance onward, architecture, painting, and sculpture formed a unified whole, which is an important factor for both the Renaissance and Baroque periods, where no clear boundary exists between the two, as both have a strong interconnectedness of art forms.

However, this strong connection ended in the 1800s. The theorists at that time believed it was best to distinguish between different art forms, assigning painting to painting, sculpture to sculpture; mixing different art forms would affect the purity they sought.

Yet, by the end of the 19th century, the idea of fusion had experienced a certain renaissance in modern art movements. For example, in Bauhaus art, we again see the idea that art forms should be interconnected. To me, this is also the most wonderful aspect of the modern art movement. At times, there exist similar ideas among architecture, painting, and sculpture, where each art form can be based on the same decorative elements, which is why decoration was so important in the Baroque and Rococo periods.

The Paper: In 2021, you co-founded the “Urban Route of Tiepolo’s Cultural Heritage” (Rete dei luoghi dei Tiepolo), which involves northern Italy and Europe. How was this cross-national exchange achieved? Why choose Tiepolo? What significant meaning does this urban route have compared to tourism projects?

Dombrowski: I am deeply involved in this project, which began during the pandemic. Initially, it was proposed by someone who lived in a small village near Venice. During that difficult time (especially when northern Italy was severely affected), he thought there should be a way to showcase the works of the Tiepolo family.