From the mid-16th to the mid-19th century, the Mughal Empire, which ruled South Asia, played a key role in composing the most dazzling chapter of Indian art history. Unlike the sculptural, architectural, and mural works of ancient India that were centered around religious beliefs, Mughal art is characterized by exquisite paintings, extravagant jewelry, luxurious clothing, and crafts with intricate compositions and vibrant colors, representing a new aesthetic paradigm for South Asia. The miniatures in the novel "My Name is Red" reflect the historical chronicles of the Mughal dynasty, marking the beginning of a systematic chronicle history in India, akin to an Indian "Records of the Grand Historian"; Shah Jahan, the Mughal emperor, built the Taj Mahal for his beloved wife, recognized as one of the Seven Wonders of the World and the "pearl of India"; Mughal jewelry, furniture, and clothing serve as inspirations for contemporary haute couture and fashion. Mughal art also unifies the currently divided nations of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, as well as parts of Afghanistan and Iran, into a coherent whole, embodying an internationalist South Asia that is inherited and coexists across national boundaries.

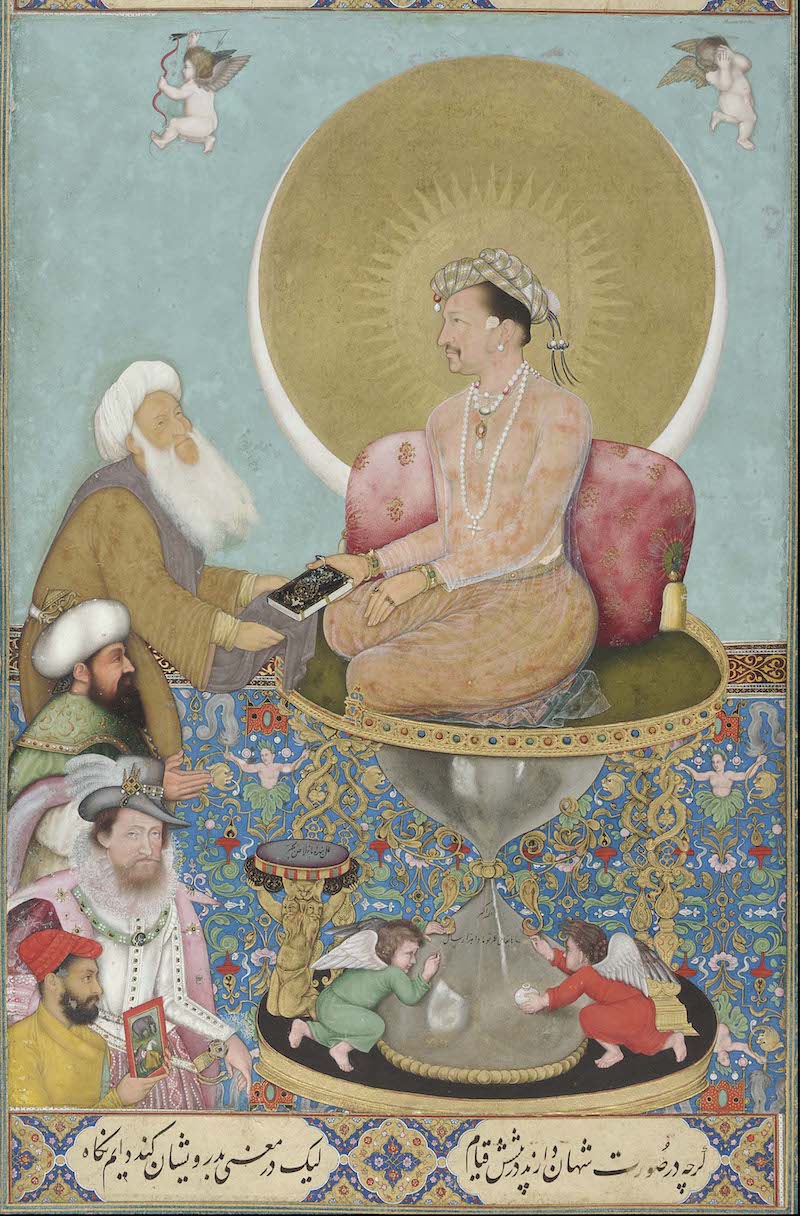

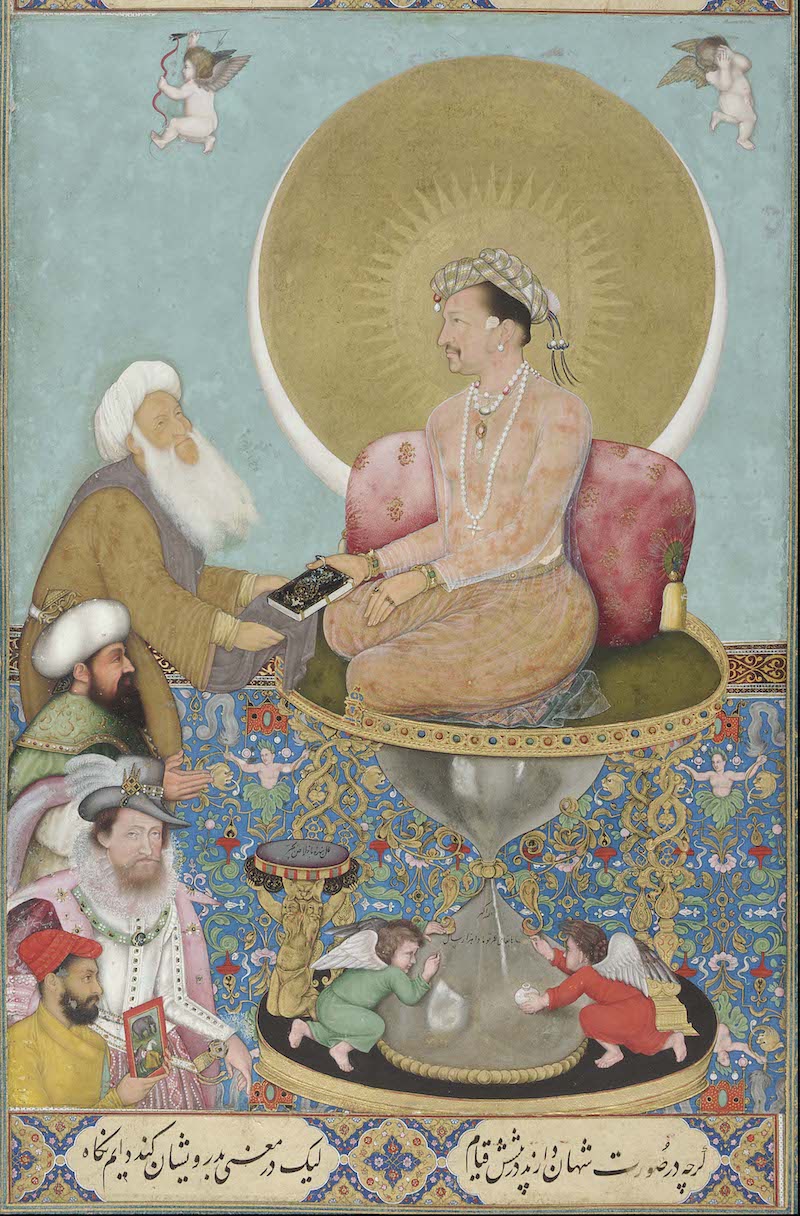

Bichitr, "Jahangir Sits on the Hourglass Throne," 1625, Mughal, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Emperor Akbar Meets the Persian Ambassadors, "Akbar Nama," 1590-95, Mughal, Image: V&A Museum

Although the Mughal Empire fell nearly 500 years ago, the issues we see in today's world, from international affairs to humorous anecdotes, are not without reason: Why did India and Pakistan partition? Why was India once a British colony? Why is Modi able to govern India? What led to the rift between seemingly unrelated India and Canada? While internet users mock India's opulent "rich weddings" and flashy "wealthy styles," they also hold Cartier and Boucheron jewelry in high regard, unaware that both represent similar cultural phenomena. Whether the tales are serious or amusing, answers found in history can lead us to a better understanding of others and the world.

The Taj Mahal in India is the most famous Mughal architecture

Watercolor of the Taj Mahal monument, 1836, Delhi, India, Image: V&A Museum

If we compare the Mughal dynasty in India with the Qing dynasty in China, it might be easier for us to understand today. Both ruled for approximately 300 years, were minority foreign rulers, and were the last feudal dynasties of their respective nations, with their fates intertwined with Western colonial powers. The literate Chinese left behind vast amounts of historical texts, yet it is challenging to gain the attention of those in today's fast-paced world; in contrast, the visually expressive Mughals utilized stunning artistic spectacles to bring modern individuals into a far-off past. There is no better channel for understanding India and the Mughals than through their art.

This article compares the three major schools of Islamic miniatures, unfolding the Mughal miniature scroll akin to imperial history records, providing a glimpse into the pastoral imagery of Rajputs and the royal allegorical paintings steeped in theological fantasy as South Asia, a corner of early globalization, resonates with an anthem of internationalism in the art of miniatures.

1. Islamic Miniatures: Ottoman, Persian, and Mughal

At the end of the 16th century, the Ottoman sultan commissioned miniaturists to secretly illustrate a great book celebrating the empire's glory. Soon after, one of the participating miniaturists died mysteriously, leading a young returnee named "Black" alongside the workshop's director to investigate the case. Upon examining the artist's butterflies, storks, and olives, they discovered the clues hidden in an unfinished miniature. Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk’s acclaimed novel "My Name is Red" opens a gateway for contemporary viewers to delve into the intricate world of miniatures, which are mystical, detailed, and resplendent, directly connecting to the spiritual palaces of Islamic rulers.

Foreign and Chinese versions of "My Name is Red"

Almost contemporaneously with the Ottoman miniatures in "My Name is Red" were the Mughal miniatures from South Asia, which, along with Ottoman and Persian miniatures, are recognized as the three major schools of Islamic miniatures. Persian miniatures began first, while Mughal miniatures elevated the Persian foundations, establishing a distinctive South Asian style; by comparison, Ottoman miniatures lack the brilliance depicted in "My Name is Red."

The Mughal Empire was a feudal autocratic dynasty established in South Asia by Babur, a descendant of the Turkicized Mongols led by Timur. It encompassed present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, parts of Afghanistan, and Iran, lasting 331 years. The capitals shifted between Agra, Old Delhi, Fatehpur Sikri in Northern India, and Lahore in Pakistan, beginning with Babur, the first emperor in 1526, and concluding with Bahadur Shah II, the last ruler, captured and imprisoned in Myanmar after the failed Indian Sepoy Rebellion in 1857. The Mughal population was about 120-158 million, accounting for approximately 20-23% of the world's population at that time.

Maps of the peak Mughal Empire in 1700 (left) and Emperor Aurangzeb (right), Image: The Howard Hodgkin Collection

Similar to the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire was founded by Central Asian Muslim nomadic tribes, making it a foreign power to India. The Ottoman Empire (1299-1923) and the Mughal Empire (1526-1857) transitioned from traditional Muslim rule to multi-ethnic, cross-regional empires significantly influenced by modern European civilization, evolving from feudal governance into modernity. The Ottoman Empire disbanded post-World War I, laying the groundwork for today’s Middle East; the Mughal Empire was the last unified state in South Asia before colonization by the British, which led to the current Indo-Pakistani partition. There were considerable cultural exchanges between the Ottomans and Mughals, reflected in Mughal art, which embraced Turkish baths and miniatures.

A black gold container inscribed with Islamic calligraphy, 1580-1600, Mughal, Image: V&A Museum

Rich with the essence of Persian civilization, the Mughal Empire exhibits significant features of Persian culture. As descendants of Timur, the Mughal rulers leaned on the Iranian Khorasan regime, leading a Persian coalition south into India to defeat the Delhi Sultanate. Kabul, in Afghanistan, was the Mughal's homeland and garden. Mughal architecture embodies Persian gardens and Central Asian styles, with early Mughal miniatures largely imitating Persian works, later developing their own distinctive style.

A miniature based on the Persian poet Nizami's "Five Poems," featuring the young Majnun (man in orange above) peeking at his beloved Leila (woman at the tent entrance), who ultimately commit suicide out of love, 1556-1565, Persian, Freer Gallery of Art

Miniatures served as illustrated manuscripts recording history for Islamic dynasties. The earliest miniatures appeared in the first half of the 13th century in Persia, where the capital of the Ilkhanate, Tabriz, became a hub, influenced by the Chinese Song dynasty's painting academy and meticulous art techniques, valuing realism and precision in depicting subjects. The peak of miniatures occurred during the Safavid dynasty (1502-1736) in Persia, coinciding with the height of Mughal miniatures, particularly during the century of Emperor Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan (1560-1660).

Comparing Ottoman, Persian, and Mughal miniature schools reveals the unique style of Mughal art.

1.1 Portraits

Left: "Portrait of an Official," 1650, Ottoman Empire; Center: Portrait by Persian miniaturist Reza Abbasi, 1609; Right: "Portrait of Emperor Alamgir," 1700, Mughal, Victoria and Albert Museum

In Ottoman and Persian portraits, the subjects are usually posed to reveal approximately 3/4 of their faces, whereas Mughal portraits reveal about half the face, a notable feature of Mughal miniatures.

Nobility in Ottoman miniatures

Ottoman portraits tend to be more formulaic and loose, often utilizing a single color with cartoonish forms; they evoke a sense of illustrated booklets or comics.

Reza Abbasi, "Youth Reading," Persia, 1625-1626

Pursuing elegance, Persian portraits exhibit lively postures, a strong sense of storytelling, harmonious and beautiful color schemes, and exquisite settings with furniture, plants, and crafts.

"Portrait of Shah Jahan," 1617, Mughal, Image: V&A Museum

Mughal miniatures borrow techniques from Persian portrait art, with finely painted backgrounds, decorations, floral page motifs, and Islamic calligraphy, showcasing rich colors. The faces reveal half, while the body shows three-quarters; although expressions and postures are less dynamic than Persian figures, standing postures are solemn, prioritizing depiction of costumes where adornments and jewelry symbolize essential aspects of Mughal identity proportionately reflected in their finery.

1.2 Architectural Structures

Architecture is a focal point in miniatures; buildings in these artworks lack perspective, presenting a comprehensive view of the scene, reflecting the belief that “God sees all,” and “nothing escapes God’s eye.” The enchanting and fantastical architecture draws viewers into a magnificent yet almost dreamlike world.