From the mid-16th to the mid-19th century, the Mughal Empire that ruled over South Asia heralded the most brilliant chapter in the history of Indian art. Unlike ancient Indian art, which centered around religious beliefs showcased through reliefs, architecture, and murals, Mughal art is characterized by exquisite paintings, luxurious jewelry, lavish attire, and fine crafts. Its compositions are delicate, with vibrant colors that are stunningly beautiful, establishing a new aesthetic paradigm in South Asia. The miniature paintings in the novel "My Name is Red" serve as a historical chronicle created by Mughal artists, initiating a systematic chronicle of Indian history—akin to a "pictorial version of the Records of the Grand Historian of India"; the Taj Mahal, built by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan for his beloved wife, is regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the World and the "pearl of India"; the exquisite Mughal jewelry, furniture, and attire continue to inspire contemporary haute couture and fashion. Mughal art has also united today’s divided nations of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and parts of Afghanistan and Iran into a cohesive whole, reflecting a persistent, pluralistic internationalism in South Asia that transcends national boundaries.

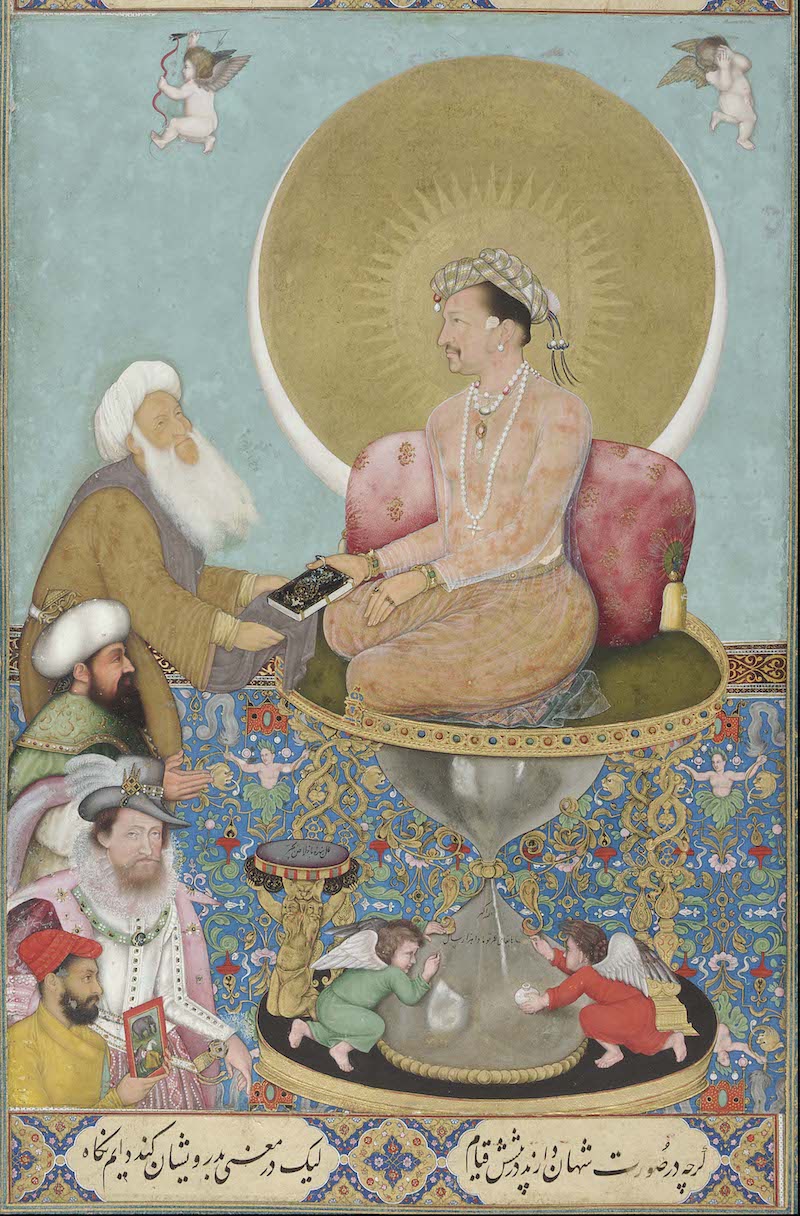

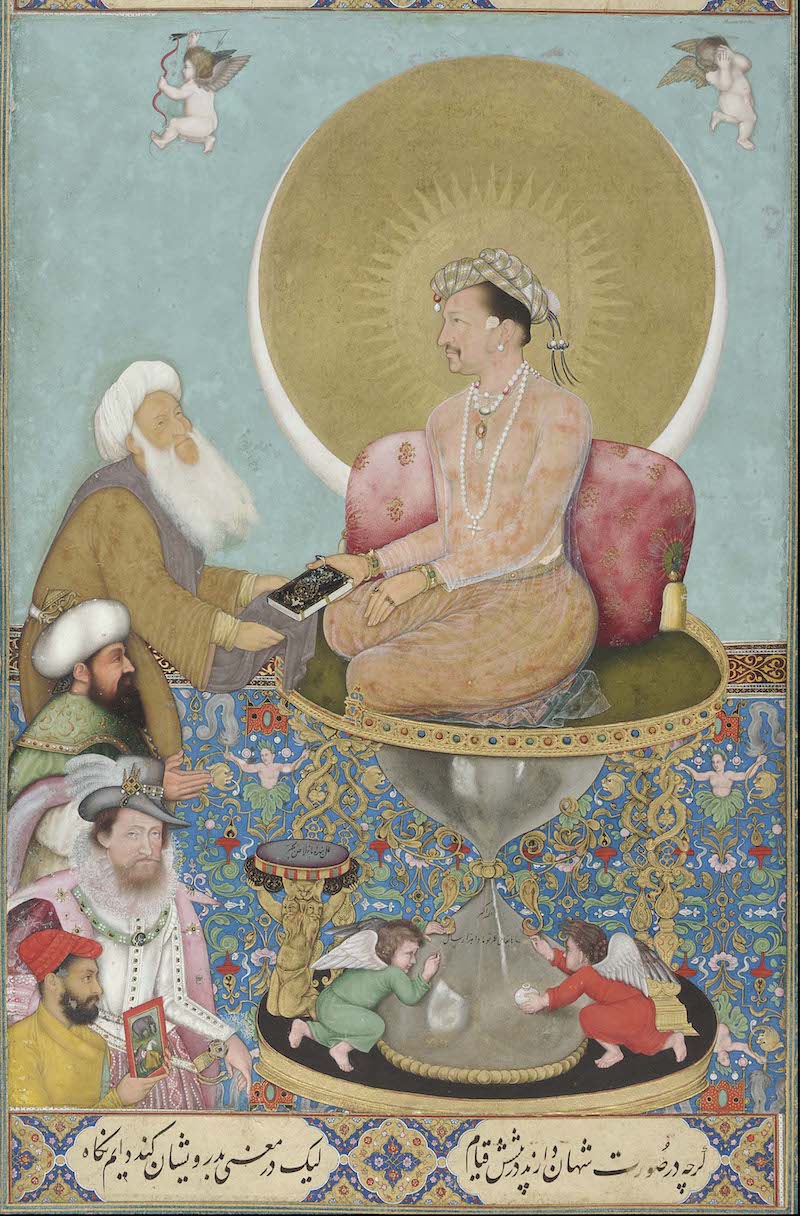

Bichitr, "Jahangir on the Hourglass Throne," 1625, Mughal, collection of the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, USA.

Emperor Akbar meeting Persian envoys, "Akbar Nama," 1590-95, Mughal, image courtesy of V&A Museum.

Though the Mughal Empire existed approximately 500 years ago, many issues in today's world—ranging from major international events to humorous anecdotes—are interconnected: Why is there a partition between India and Pakistan? Why was India once a British colony? Why is Modi able to govern India? Why do seemingly unrelated India and Canada have tensions? When netizens mock the opulence of Indian "rich weddings" and the flashy "rich style," they often revere Cartier and Boucheron jewelry without realizing that both represent the same essence. By seeking answers within history, one can better understand others and the world, whether the anecdotes are serious or humorous.

The Taj Mahal in India is the most famous Mughal building.

Watercolor of the Taj Mahal, 1836, Delhi, India, image courtesy of V&A Museum.

By comparing the Mughal Dynasty in India with the Qing Dynasty in China, we might find it easier to comprehend the present day. Both dynasties lasted approximately 300 years and were governed by foreign ethnic minorities, ultimately representing the last feudal dynasties of their respective countries, with their fates ending due to Western colonial incursions. The Chinese, adept at recording history, produced a vast array of historical texts, yet they often struggle to capture the attention of people in the fast-paced modern age. In contrast, the Mughals utilized their stunning artistic marvels, immersing contemporary viewers in a distant past. There is no better conduit for understanding India and the Mughals than through art.

This article compares three major schools of Islamic miniatures, unfolding the Mughal miniature paintings like a historical chronicle, ranging from theological fantasy themes depicting royal symbolism to the idyllic pastoral scenes of the Rajputs, showcasing South Asia as a corner of early globalization, where internationalism resonates through the art of miniatures.

1. Islamic Miniatures: Ottoman, Persian, and Mughal

In the late 16th century, the Ottoman Sultan commissioned miniature painters to secretly create a grand book, celebrating the glory of the empire. Shortly after, some of the artists involved in the project mysteriously died, leading a young "black" to return home and team up with the studio head to investigate the murders. While probing into the butterfly, stork, and olive themes depicted by the artists, they uncovered clues hidden within an unfinished miniature. Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk's acclaimed novel "My Name is Red" opened the door for contemporaries into the world of miniatures, showcasing their mysterious, intricate, and luxurious nature, directly connecting to the spiritual realms of Islamic rulers.

Foreign and Chinese editions of "My Name is Red."

Almost contemporaneous with the Ottoman miniatures depicted in "My Name is Red," are the South Asian Mughal miniatures, alongside Ottoman and Persian miniatures, forming the three major schools of Islamic miniatures. The earliest wave of Persian miniatures laid the foundations, which the Mughal immersion elevated, creating a unique South Asian style. In contrast, the Ottoman miniatures are not nearly as dazzling as described in "My Name is Red."

The Mughal Empire, established by Babur, a descendant of the Turkicized Mongol Timur, reigned over South Asia for 331 years, covering modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, parts of Afghanistan, and Iran. Its capitals rotated through Agra, Old Delhi, Fatehpur Sikri, and Lahore in Pakistan. It began with Babur in 1526 and concluded with the capture of the last emperor, Bahadur Shah II, following the failure of the Indian Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, who was subsequently exiled to Myanmar. The population of the Mughal Empire was around 120-158 million, about 20-23% of the world population at the time.

Map of the Mughal Empire at its zenith in 1700 (left) and a portrait of Emperor Aurangzeb (right), image courtesy of The Howard Hodgkin Collection.

Similar to the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire was founded by Central Asian Muslim nomads, thus serving as an external regime for India. The Ottoman Empire (1299-1923) and the Mughal Empire (1526-1857)—one a Near East/Middle Eastern empire and the other in South Asia—both transitioned from traditional Muslim governance towards polyethnic and cross-regional dominions, influenced by modern European civilization and evolving from feudal systems to modernization. The Ottoman Empire disbanded after World War I, which shaped today's Middle East; conversely, the Mughal Empire represents the last unified regime of South Asia before it became a British colony, leading to the current partition between India and Pakistan. There were numerous cultural exchanges between the Ottomans and the Mughals, with Mughal art encompassing Turkish-style baths and miniatures.

A black gold container inscribed with Islamic calligraphy, 1580-1600, Mughal, image courtesy of V&A Museum.

The pronounced Persian cultural core is a significant characteristic of the Mughal Empire. As descendants of Timur, the Mughal rulers used the power of the Iranian Khorasan state to forge an alliance with Persian forces, defeating the Delhi Sultanate and heading south into India. Kabul in Afghanistan was regarded as the Mughal homeland and garden. Mughal architecture features Persian gardens and Central Asian styles, with early Mughal miniatures largely replicating those of Persian origin; later, however, they developed their own distinct style.

A miniature depicting a scene from Nizami's "Five Poetries," featuring Majnun hiding outside a tent, peeking at his beloved Laila (standing at the tent entrance), with the two eventually committing joint suicide, 1556-1565, Persian, collection at the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Miniature paintings served as illustrations for manuscripts, utilized by Islamic dynasties to document history. The earliest miniatures appeared in the early 13th century in Persia, with the capital of the Ilkhanate, Tabriz, being a center for miniatures, influenced by China's Song dynasty painting systems and the meticulous painting style, emphasizing realistic representation through delicate detailing to convey meaning through form. The pinnacle of miniature art occurred during the Safavid dynasty in Persia from 1502 to 1736, and likewise marked the height of Mughal miniatures, occurring during the reigns of three emperors: Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan from 1560 to 1660.

By comparing the Ottoman, Persian, and Mughal miniature schools, we can grasp the unique characteristics of Mughal miniatures.

1.1 Portraits

Left: "Portrait of an Official," 1650, Ottoman Empire; Center: Portrait by Persian miniaturist Reza Abbasi, 1609; Right: "Portrait of Emperor Alamgir," 1700, Mughal, collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In Ottoman and Persian portraiture, the subjects are shown at a slight angle, revealing three-quarters of their faces, whereas Mughal portraits typically reveal only one-half of the face. This characteristic is a distinctive feature of Mughal miniatures.

Nobleman from Ottoman miniature.

Ottoman portraits are often more formulaic and rough, with a single color palette, cartoon-like shapes reminiscent of comic books.

Reza Abbasi, "Youth Reading," Persian, 1625-1626.

Pursuing elegance, Persian portraits depict lively poses with strong storytelling elements, harmonious colors, and intricate scenery furnished with furniture, plants, and decorative items.

"Portrait of Shah Jahan," 1617, Mughal, image courtesy of V&A Museum.

Mughal miniatures borrowed from Persian portrait techniques, rendering detailed backgrounds, decorations, floral margins, and Islamic calligraphy with a rich color palette. While the face is displayed half-visible, the body appears three-quarters visible, and expressions and poses are less dynamic compared to the Persian portrayals, with a more solemn stance. The emphasis is placed on attire; garments and jewelry are significant symbols of Mughal identity, with lavish dressing indicating royal status.

1.2 Architectural Elements

Architecture is a focal point in miniatures, depicted without perspective and presenting a flat view of the entire scene, embodying the belief that "God sees all" and "nothing escapes the eyes