Egon Schiele (1890-1918) was an expressionist painter in the early 20th century and a representative of the Vienna Secession. In the last few years of his life, Schiele created some works with psychological insight.

Recently, the Oppold Museum in Vienna, Austria, held a special exhibition "Times of Change: Egon Schiele's Last Years (1914-1918)", presenting the artistic evolution of Schiele's works in his later years. During this period, his lines became more peaceful and smooth, he began to pay attention to "human psychology", and the characters he depicted became more three-dimensional.

On October 27, 1918, Egon Schiele sketched his wife Edith, who was pregnant and lying in bed with a fever. The next day, she died of influenza. Three days later, Schiele died too.

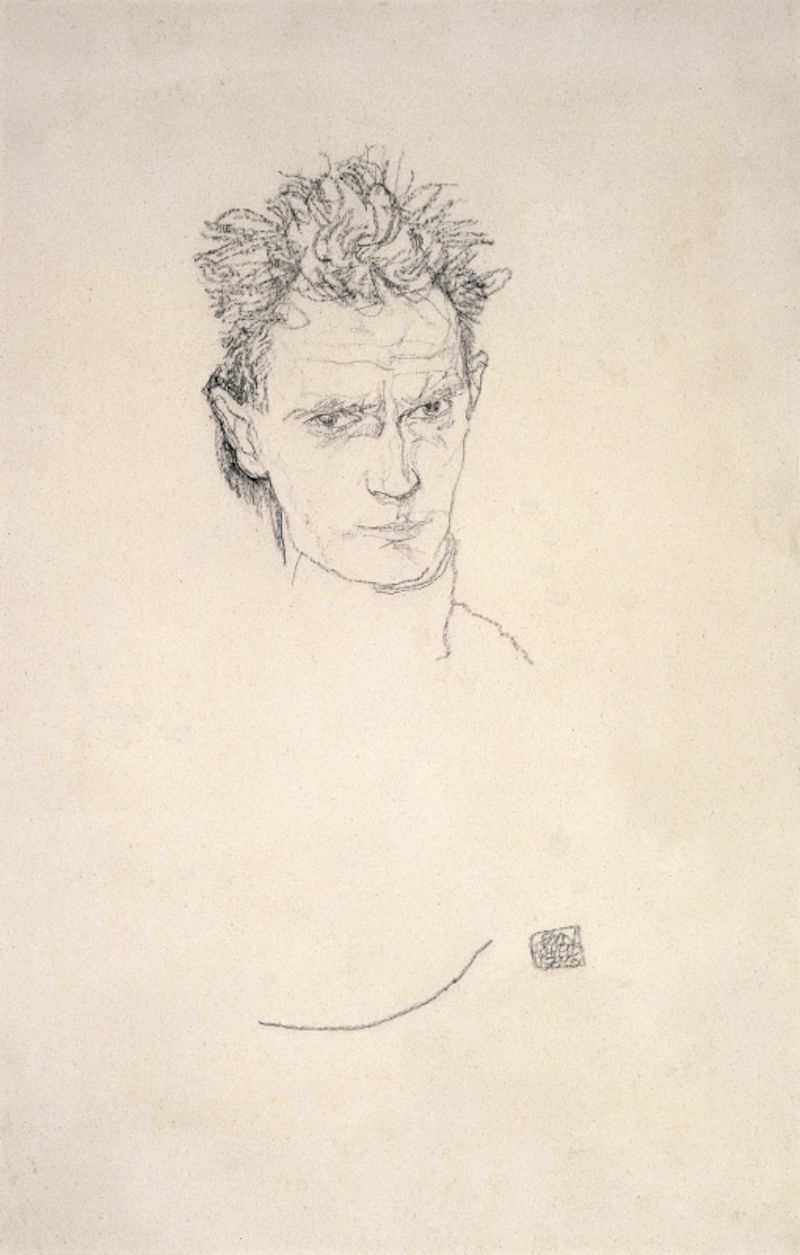

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait, 1916

Edith, 25, and Egon Schiele, 28, were two of an estimated 50 million victims of the Spanish flu that devastated Europe. Over the course of a decade, Schiele depicted his intimate life in art, creating around 3,000 drawings and 400 paintings.

Schiele and his wife Edith in 1917

Today, Schiele is often associated with the erotic nude portraits he created from 1909, when he dropped out of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, until around 1914. But Kerstin Jesse, senior curator at the Leopold Museum in Vienna, Austria, believes that Schiele's more mature and sober work is often overlooked.

Now, the special exhibition "A Changing Time: Egon Schiele's Last Years (1914-1918)" at the Oppold Museum is trying to change people's perception. In this exhibition, about 130 original works of the artist and dozens of personal documents will give the audience a new understanding of Schiele's later life.

Exhibition site

"I wouldn't say the late works are better than the early works, or vice versa. They're just very different periods in Schiele's life and career," said Jane Kallir, who co-curated the exhibition with Jesse. Schiele's early works are what Kallir calls his "expressionist breakthrough." They use sharp lines and soft colors to depict sensual and contorted bodies, often from figures in Viennese high society.

In 1912, Schiele was arrested on charges of displaying indecent drawings. He spent 24 days in jail. At the time, he was also in an infamous affair with his strawberry-blonde model, Walburga Neuzil, whom he included in his famous 1912 painting, Portrait of Walburga Neuzil, at the age of 16.

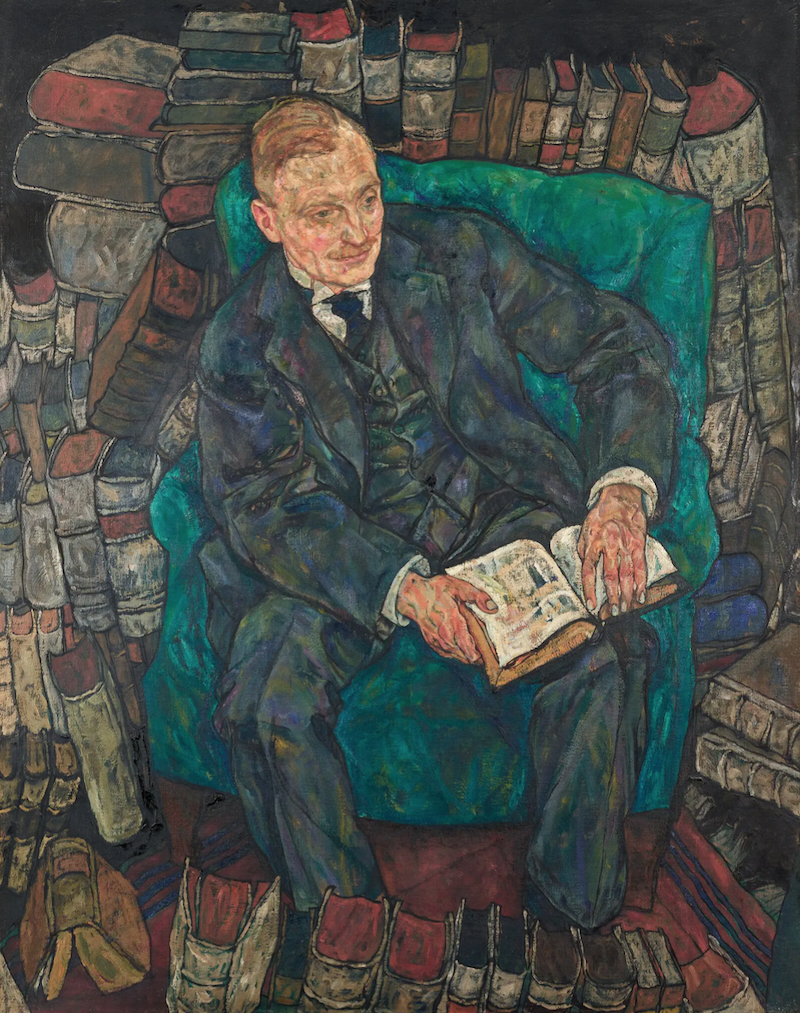

Portrait of Dr. Hugo Kohler by Egon Schiele

Schiele's "Infant (Anton Peschka the Younger)" in pencil and gouache, 1915

Schiele's wild life ended in 1914 when World War I broke out. His sister Gertrude settled down with his best friend, Anton Peschka. The couple's first child was born before the marriage and sent to live with their grandmother. Later, they had a second child. Becoming an uncle changed Schiele. Kalil said that becoming an uncle changed the artist's views on relationships, parenthood and women, and he became more thoughtful and serious.

In a letter to his sister on November 23, 1914, Schiller wrote, "We live in the most violent times the world has ever seen... Each of us must bear the fate of life or death. We have become tough and fearless. Everything before 1914 belongs to another world, so we will always look to the future..."

Schiele shifted his focus to the emotional lives of his subjects, rather than their gestures or sexuality. He began to focus on the "psychology of man," and he really captured the personalities of other people.

Portrait of Schiele's wife Edith Schiele

Schiele's skills as an artist also developed. "He had a technical breakthrough in his control of the drawing and painting medium," Kelsting said. "His drawing style became more graceful, more voluminous, more realistic, and his painting style actually became more expressionistic, with bolder, thicker brushstrokes and brighter colors."

In 1915, after breaking up with Neuhl, Schiele married Edith Harms, a demure, middle-class woman of his own age. Edith’s diary, a gift from Schiele before their marriage, reveals intimate details of their mostly unhappy life. The diary is on display in the exhibition and published for the first time.

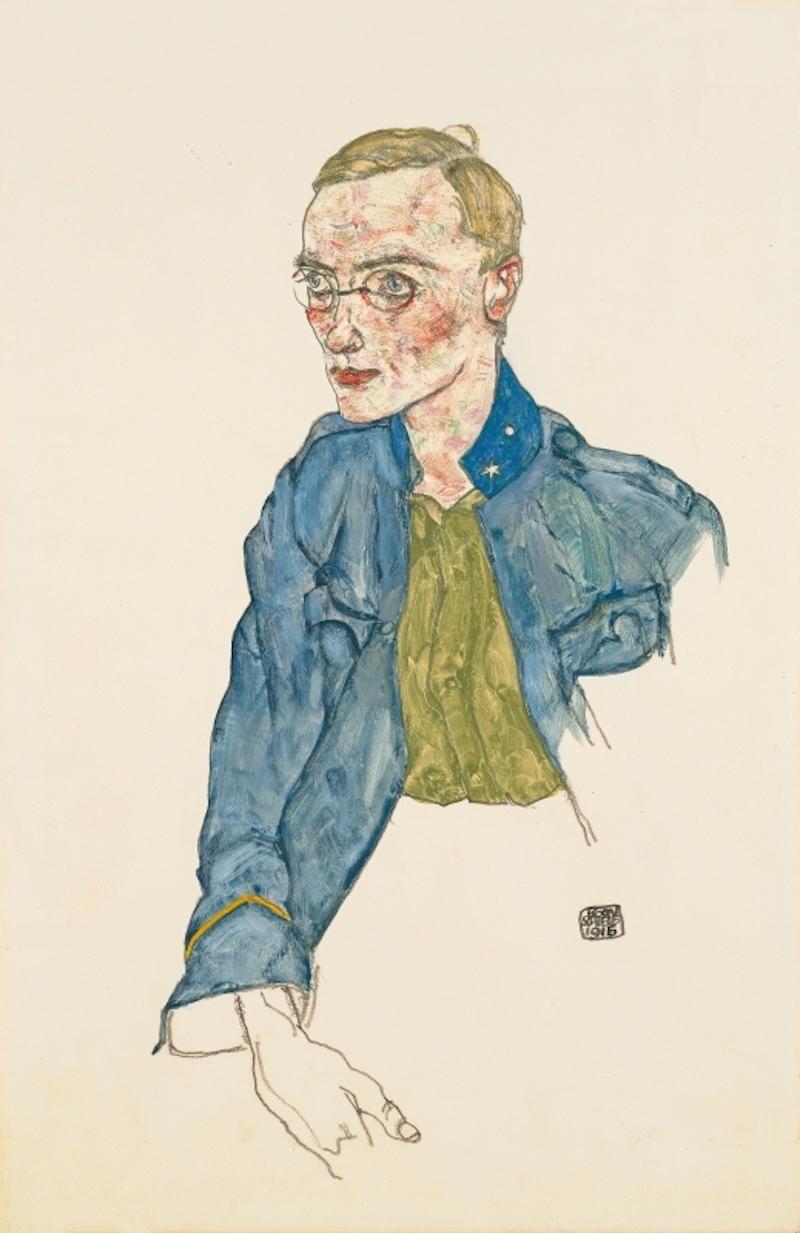

Egon Schiele, One Year as a Volunteer Corporal, 1916

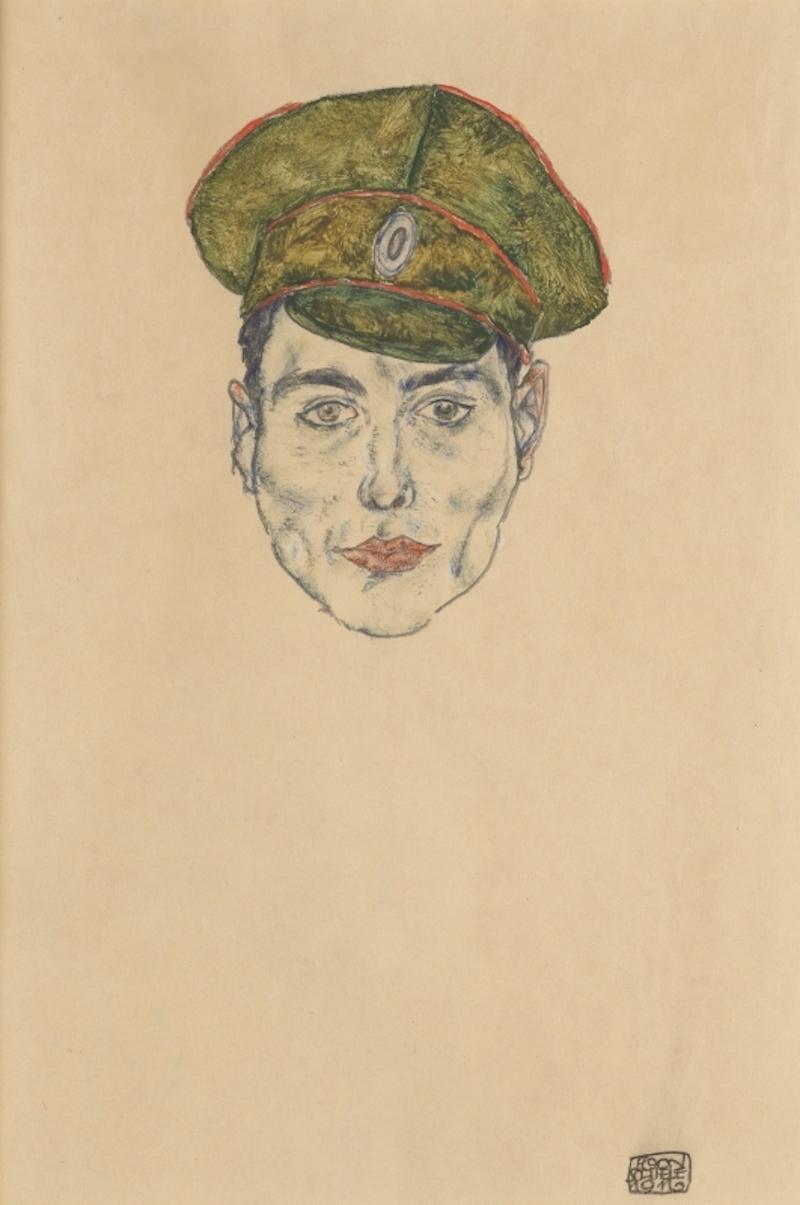

Egon Schiele, Russian Soldiers, 1916

After a hasty honeymoon, Schiele had to go to the army. He left Edith in a hotel in Prague, leaving a little money and some sketches that he asked her to sell in exchange for food. But Schiele hated military service and wrote to many people in search of an escape. In January 1917, an antique dealer named Karl Grünwald managed to transfer him to a military supply station in Vienna, giving him relatively less responsibility. In this way, he could once again focus on his art.

In the last year of his life, many of Schiele's creative goals began to crystallize. His new status was confirmed by the sale of his works at the famous Vienna Secession exhibition in March 1918. "Schiele was an artist whose mission was to reconcile the contradictions between realism and expressionism, psychological insight and spirituality. He was always grappling with these issues. In his late works, he reached a different level of integration of these elements," said Kalil.

In 1918, Schiele designed a poster for the 49th Vienna Secession Exhibition. In the poster, Schiele is sitting at a table with his friends sitting around him.

“You can see that his lines become more fluid, calmer and less rigid,” curator Kersting said of the artist’s later portraits. “His early works showed very gaunt figures, but later on, the bodies of his figures began to have life, heartbeats, and vitality.”

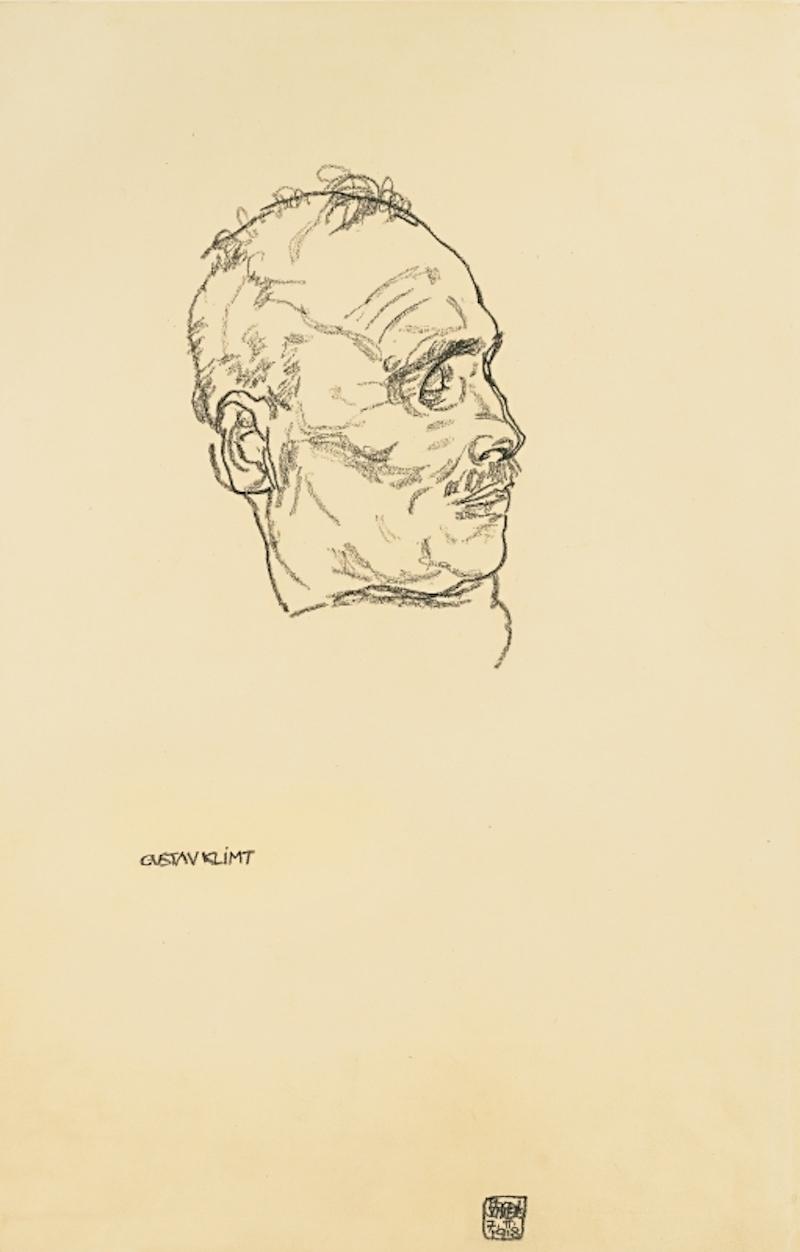

Yet even as Schiele’s work was taking on new life, the pandemic that would lead to his death was gathering pace. Influenza had begun to spread after World War I, and in February 1918, Schiele’s friend and mentor, Gustav Klimt, likely died of a flu-induced stroke and pneumonia. Schiele painted Head of the Late Gustav Klimt in response.

Egon Schiele, The Embrace (Lovers II), 1917

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman, 1917

Schiele's last oil painting, a portrait of his friend, the painter Albert Paris von Gütersloh, shows that he was at the "peak of his art" at the time of his death on October 31, 1918.

Egon Schiele, Head of the Late Gustav Klimt, 1918

Schiele's last oil painting was a portrait of his friend, the painter Albert Paris von Gütersloh.

Jesse said it was hard to imagine what Schiele would have created if he had had more time. However, his contribution to art history is already huge. "Some artists create the same amount of work in a career of 50 or 60 years. He died very suddenly. So we don't know which path he would have taken afterwards."

The exhibition will run until July 13th.

(This article is translated from The New York Times, and some content comes from the museum's official website)