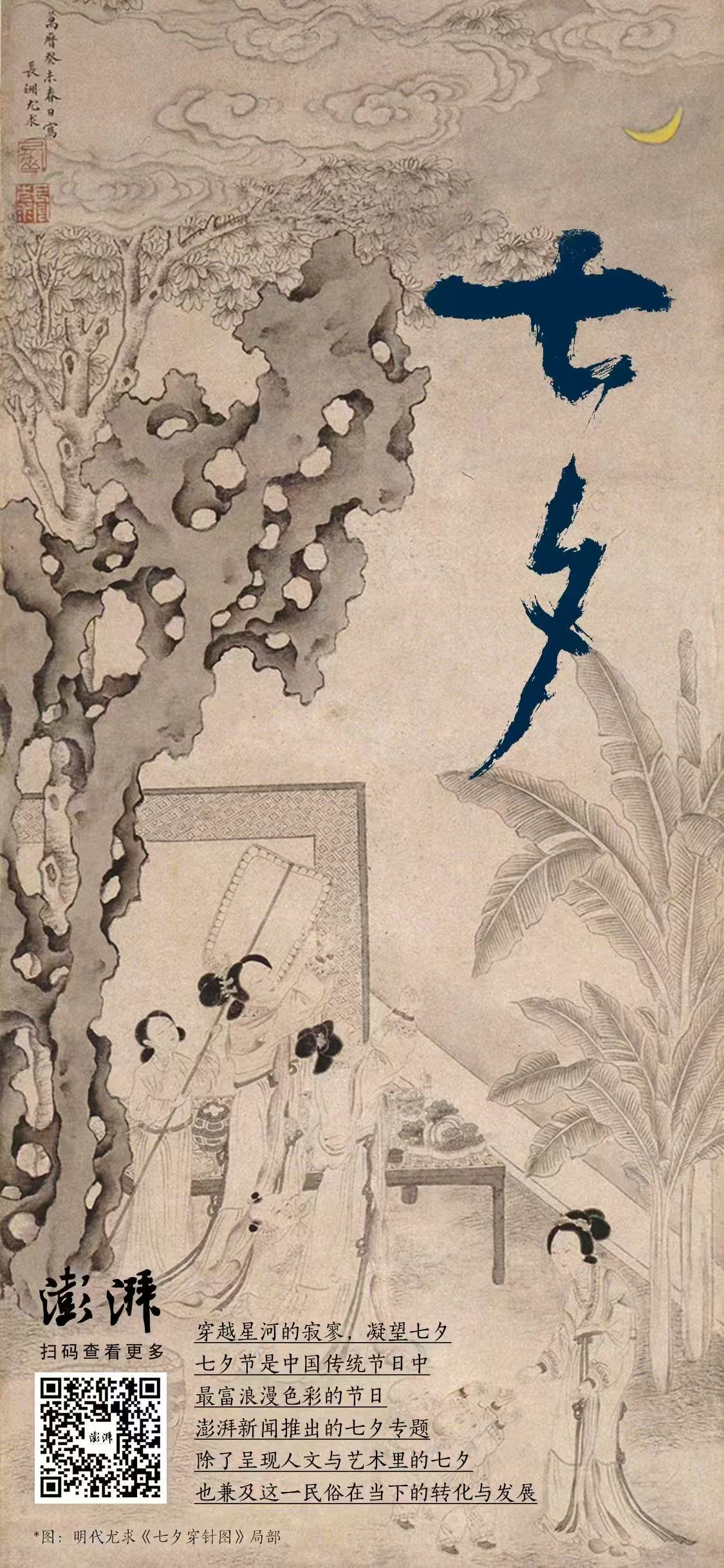

Since ancient times, the night of Qixi Festival has been a romantic occasion for praying for ingenuity and expressing affection. Beyond the legend of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, another cultural iconography—the lotus and child motif—has quietly permeated Qixi folklore and art, becoming a unique symbol connecting religious beliefs, folk prayers, and the refined tastes of literati. Patterns are the code of civilization, carrying the beliefs and emotions of the ancients.

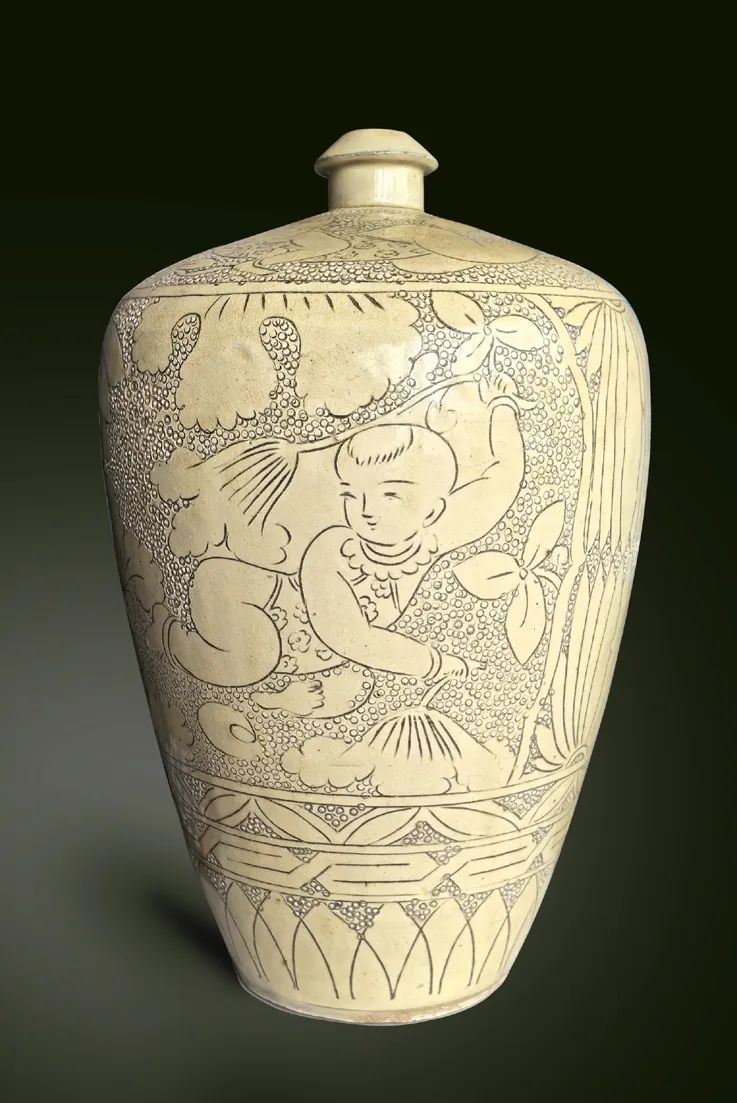

Detail of a Song Dynasty plum vase with a black painted white background and a lotus-holding boy pattern

The lotus boy pattern combines the purity of Buddhism with secular wishes, and on the poetic festival of Qixi Festival, it interprets a rich narrative from religion to folk customs, from the palace to the market.

【Double-headed Lotus】

Lotuses bloom in June and July, coinciding with Qixi Festival (Chinese Valentine's Day), making them a natural symbol of this festival. Over four hundred years later, Emperor Kangxi still composed the poem "Viewing the Thousand-Petal Lotus on Qixi Festival." "When the flowers are in bloom, they must be picked." Northern Song Dynasty poet Xu Xuan twice picked lotus flowers on Qixi Festival, capturing the exhilaration of "drunkly picking lotus flowers, dreaming of gorgeous makeup" in "Fenghe Qixi Yingling" (Another Poem on Qixi Festival), and the loneliness of "picking lotus flowers in a waterside pavilion" in "Qixi in the Posthouse." Compared to the loneliness of a foreign land, as depicted in Meng Haoran's poem "Who can bear to gaze at the Milky Way, and ask about the distant battle of the Bull?", Xu Xuan's lotus blossom seems to carry a touch of warmth and companionship.

"Dongjing Menghualu" records that "the lotus flowers have not yet bloomed, so the people in the city are good at making them into double-headed lotus flowers, playing with them for a while, and then carrying them home."

During the Qixi Festival, it was a common custom among the common people to pick and break lotus flowers and give them as gifts. This is evident in Fang Yue's poem "Magpie Bridge Fairy, Part 1: Giving Lotus Flowers on the Qixi Festival" from the Southern Song Dynasty. According to the "Dongjing Menghualu," the people of Bianjing loved to imitate unopened lotus flowers by creating twin lotuses: "They would pick unopened lotus flowers and create a double-headed lotus, playing with them for a while and then carrying them home." The method typically involved piercing the stem with a stick, securing the two buds to the same branch to simulate the appearance of a twin lotus. In the Song Dynasty, twin lotus flowers were considered auspicious, as Wu Fu noted, "The twin lotus flowers are a natural sight, a sign of good fortune."

The author's homemade lotus

The imagery of twin lotuses is also deeply ingrained in clothing and literature. Liu Lingxian famously coined the line, "Stitching needles together to imitate twin lotuses." During the Song Dynasty, "court ladies and market girls adorned their crowns and collars with ornaments inspired by the Qiqiao period." For example, the hem of a silk gown unearthed from a Song Dynasty tomb at Chayuanshan in Fuzhou features a small lotus pond scene depicting twin lotuses. The Song people particularly favored double-headed flowers and fruits, viewing them as a symbol of "Jiaxiang," leading to the creation of ci tunes such as "Twin Lotuses" and "Double-Headed Lotus."

True twin lotus flowers are extremely rare and often associated with auspiciousness and fame. Hong Mai's Yijianzhi records the story of Jia An's success in the imperial examination after seeing a twin lotus at his residence. Ming Dynasty poets Wu Maoqian and Qing Dynasty poets Qian Xiang also wrote poems about twin lotus flowers during the Qixi Festival, using lines like "blooming twin lotus flowers" and "twin stars should be pitied," blending natural phenomena with human sentiment. After the Yuan and Ming dynasties, the name "Double Lotus Festival" emerged. As recorded in "A History of Love," Chen Feng and Ge Bo produced twin flowers after a lotus seed fell into the water, prompting the villagers to change the name to "Double Lotus Festival." While the authenticity of this story remains questionable, it reflects the profound influence of the lotus on Qixi Festival traditions. Just as the line "bending down to play with lotus seeds, the seeds are as clear as water" conveys a subtle and affectionate sentiment, it also explains the Qing Dynasty poet Wu Xiqi's lament, "I am celebrating the twin lotuses, how can I contain my sorrow?"

Song and Yuan Dynasty "Cizhou Kiln Plum Vase with Lotus Boy Pattern"

【Metamorphosis】

The fragrant heart is intimate with the clever heart, the branches of the albizzia tree are intertwined. Under the double-headed flower, two hearts are in harmony, and a pair of children are born.

——"Nine Looms" by Anonymous, Song Dynasty

The introduction of Buddhist Pure Land thought into China can be traced back to the late Eastern Han Dynasty. By then, scriptures promoting the faith in Amitabha Buddha had already been gradually introduced to the Central Plains. The Pure Land, the sacred realm where Amitabha Buddha resides, holds a revered position in Mahayana Buddhism. According to incomplete statistics, approximately one-third of existing Mahayana sutras contain passages praising Amitabha Buddha. During the heyday of the Tang Dynasty, the monk Huaiyu once chanted: "Pure and bright, free from dust and stain, lotus is born as one's parents." Lotus birth is considered one of the core pathways to rebirth in Amitabha's Pure Land, and images often depict a child emerging from a lotus. This image's significance in Pure Land belief is comparable to the importance of Amitabha Buddha in Buddhist texts.

The Transformation Boy in the "Repaying Gratitude Sutra" in the Dunhuang Caves of the Tang Dynasty, from the British Museum

In 1988, Yang Xiong, while discussing the transformation-born children depicted in the Mogao Grottoes murals in his book "Dunhuang Studies," noted that the "Transformation of the Avalokitesvara Sutra" on the south side of Cave 148 depicts over ten transformation-born figures. Each figure is accompanied by a plaque, with identifiable titles such as "First Grade Rebirth," "Middle Grade Upper Rebirth," "Upper Grade Middle Rebirth," and "Upper Grade Lower Rebirth," demonstrating the mural's faithful representation of the sutra's content. These distinctions have clear doctrinal basis. For example, those who are reborn in the Lower Grade Upper Rebirth, because they "join their palms together and chant 'Namo Amitabha,'" are able to "follow the transformation Buddha and be born in the Treasure Pond, where after seven days the lotus blossoms." While those who are reborn in the Lower Grade Middle Rebirth are also "born within the lotus in the Treasure Pond," they must "sit in the lotus for six kalpas before the lotus blossoms." As for the Lower Grade Lower Rebirth, those who are reborn must "sit in the lotus for twelve great kalpas" before the lotus blossoms. While transformation-born is not the only way to attain rebirth in the Western Paradise, cultural relics and historical records indicate that it was highly regarded by Pure Land believers of the time. The images of transformations in images are often children, also known as "transformed children" or "transformed children." The Tang Dynasty Dunhuang song "Ten Praises of Transformed Children" is well-known, and the Southern Song Dynasty's Fan Chengda also wrote "Yu Han Transformed Child," both referring to this type of image.

Suzhou Luohanyuan Twin Towers

Transformation images are not only found in murals but also widely appear in ancient architectural decorations. Wang Xiuling's article "Research on Northern Wei Lotus Tile Ends" concludes: Based on the few clearly identified Northern Wei structures, they were primarily used in imperial temples, most likely pagodas. The general pattern of their evolution is as follows: "In the early period, the transformed boy was not stout, with hands spread apart and close to the shoulders, a collar around his neck, and a "flower rope" in his hands. In the middle period, the transformed boy's body became thinner, with his hands gradually closer together, either holding a water bottle or clasped together. Some boys wore scarves or armlets. In the late period, the transformed boy was extremely slender, with his hands clasped together, and he wore scarves, a halo, and a back halo."

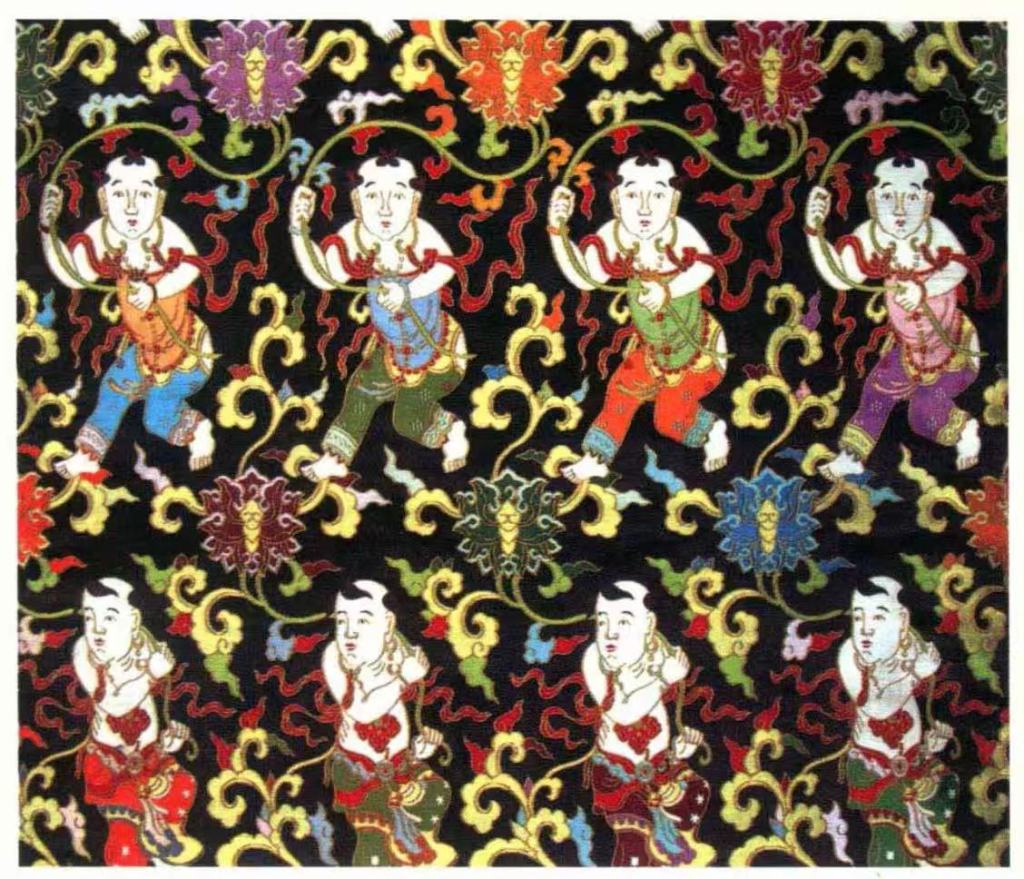

Boy climbing lotus flower satin Source: Nanjing Brocade

Buddhist scriptures are filled with stories of reincarnation, such as the story of the deer girl in the Miscellaneous Treasures Sutra, who gave birth to a thousand-petal lotus, each containing a child, which she took and raised. Although the reincarnated boy in Buddhism originally did not inherently serve the purpose of praying for children, the image of the boy, coinciding with Chinese tradition that linked the success or failure of a family with the continuation of its descendants, gradually came to symbolize the wish for offspring.

In Pure Land Buddhism, Amitabha's Pure Land is a purely male realm, devoid of women. "Women from other lands who wish to be reborn in Amitabha's Pure Land will, upon death, be transformed into male bodies, born within the seven-treasure lotus of that Pure Land." Since women can be reborn as men through transformation, the image of a transformed child naturally garnered greater veneration from those seeking children. This image gradually became ingrained in folk customs of "seeking children," becoming a symbol of the wish for both sons and grandsons. The Tang Dynasty's "Nianxia Sui Shi Ji" records: "On the Qixi Festival, it was customary to make wax figures of babies and float them in water for entertainment. This was considered a sign of a woman's wish for a child, and was called 'transformation.'" This suggests that by the Tang and Song dynasties at the latest, "transformation" clearly carried the auspicious connotation of "preparing for children."

"The Lotus-holding Boy among the Two Immortals of Harmony and Unity" from the Qing Dynasty

【Mohele】

The Lotus Boy is also known as the "Lotus-Holding Boy," "Mohu Luo," and "Mohe Le." Mohe Le is a common sight in the notes of Song Dynasty figures and is a key item for the Qixi Festival. Its name, derived from a Buddhist transliteration, is also known as "Mahu Luo," "Mahe Luo," "Mohe Luo," "Mohe Luo," and "Maha Luo." Scholars have extensively researched its origins, but in the secular context of the Song Dynasty, the Mohe Le gradually shed its original religious significance and evolved into a childlike figure. It served as both a seasonal offering during Qixi Festival ceremonies and a popular folk toy.

The "Dongjing Menghualu" records: "On the seventh night of the seventh month, the tile shops outside the Dongsong Gate in Panlou Street, the tile shops outside the Liang Gate in the west of Zhou, the Beimen Street, the Nanzhuque Gate Street, and Maxing Street all sell Mohele (small clay figurines)." These figurines often have carved wooden pedestals or are adorned with red gauze and jade. Some are inlaid with gold beads, ivory, or jadeite, and a pair can cost thousands of coins. "The imperial court, the nobles, and the common people all use these as seasonal ornaments." Whether among the court, the nobility, or the common people, these items are treasures for the Qixi Festival. Before the festival, Mahora statues are displayed in the inner court and the homes of the nobles. The Xiu Nei Si customarily presents ten tables, each with thirty seats. The largest ones are three feet tall and are made of either carved ivory or ambergris, adorned with gold beads and jadeite. Their clothing, jewelry, accessories, and even the toys they hold are all meticulously crafted from the "Seven Treasures."

Yuan Dynasty, Anonymous, "Summer Scene with Children Playing" (detail), National Palace Museum, Taipei

"Three to five days before Qixi Festival, the streets are filled with carriages and horses, and silk and satin adorns the air." People of the time delighted in plucking unopened lotus leaves, skillfully crafting them into double-headed lotuses, which they would play with while strolling, drawing admiration and admiration from passersby. Children would also buy new lotus leaves and hold them in their hands, imitating the poses of Mahārā. On this day, children all wore new clothes, "competing in their splendor," their attire as adorable as Mahārā. This custom spread to the Jiangnan region with the Song dynasty's migration southward. Images of children holding lotus flowers can often be seen in Song Dynasty paintings of children at play—whether this originated from the custom of "transformation" or was inspired by Mahārā is difficult to distinguish.

Ding kiln boy holding lotus pillow, collection of the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, USA

Yuan Dynasty white jade carving of a boy holding a lotus, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Initially, "Huasheng" and "Mohele" had different origins, but as time went on, by the Southern Song Dynasty, the two had gradually merged and could even refer to each other. Yang Wanli wrote in "Two Poems to Thank Yuchu for Sending Huashenger Wine, Fruit, Honey and Food for Qixi Festival, Part One":

Suddenly, the courtyard is full of stumbling children and grandchildren, picking lotus leaves and riding bamboos, spring orioles on their arms. The night after the clever building, I invited the Cowherd and the Daughter, leaving the key to send them off to the next generation. Festival gifts urge people to grow old, and the wine cup is poured out in joy of the gift. Drunkenly sleeping, I can only watch the Milky Way magpie, returning from heaven to ring the sixth watch.

This suggests that, due to their similar shapes and meanings, the terms "Huasheng'er" and "Mohele" were already interchangeable by the Southern Song Dynasty at the latest. Because Mohele was often made of clay, it was also commonly known as "Nihaier." "Wulin Jiushi" (Old Things in the Wulin) refers to it as "called Moluo," and some exquisitely crafted ones, adorned with gold beads, were extremely valuable. Lu You's "Notes from Laoxue'an" also describes the clay dolls made by the Tian family of Fuzhou as "famous throughout the world, with endless charm." Even craftsmen in Beijing tried to imitate them, but none could match them. Although generally useless, clay dolls are extremely popular during the Qixi Festival. They can be found in many Kaifeng markets, in various shapes and sizes, adorning men's and women's clothing. They command a high price, with some exquisitely crafted ones even inlaid with gold and beads, representing a truly luxurious experience.

Rich families used exquisite clay figurines to pray for a long line of offspring, while on the other side of society, Xu Wei of the Southern Song Dynasty, in his poem "Clay Children," described the tragic reality of poor babies abandoned on bridges and alleys:

Mudu is a lump of clay, adorned with extravagant sculpting. Alas, its flesh is too thin to bear the weight of gold and pearls. Covered in red gauze, it stands delicately beneath a vase of flowers. A young woman, tasting something sour for the first time, delights in every moment. I secretly pray to the Bodhisattva, wishing for a child like you. But who knew the child from this impoverished family would be thinner than a ghost? Abandoned on a bridge or in an alley, no one cares whether he lives or dies. Humans are worth less than clay; only three sighs can do that.

The fate of the "clay child" from a wealthy family in the poem forms a sharp contrast with the real baby from a poor family, deeply reflecting the sad reality of the gap between the rich and the poor in Southern Song society and the fact that people are worse than clay.

The starry sky of Qixi Festival remains as dazzling as ever, and the lotus and child motif has long transcended the confines of a single season. A twin lotus, a pair of transformed children, a piece of Mohele—seemingly small objects, yet they carry the ancients' yearning for a better life, their wishes for a long line of descendants, and even their contemplation of the Pure Land beyond life and death. Like the starlight of Qixi Festival, they illuminate the delicate and profound cultural threads of history. They remind us that civilization constantly regenerates through such integration and reinvention.