“The drifting summer clouds disperse, a gentle cool breeze rises.” This line is from a poem by Bai Juyi from the Tang Dynasty; “A slight breeze under the fan, remembering the moments shared with that person, delicate hands peeling the lotus seed pods.” This is a line from a painting title by Jin Nong of the Qing Dynasty.

Today marks the end of summer—Chushu, the second solar term of autumn. The term Chushu literally means “the end of heat,” signifying the departure of hot weather. The scorching summer draws to a close, and the coolness of autumn begins to set in, marking the cessation of summer and heralding the arrival of autumn’s chill. During Chushu, there are three meteorological signs: “First, the eagle begins to offer sacrifices to birds; second, the heavens and the earth start to grow solemn; third, the grain begins to ripen.” Customs associated with Chushu include the opening of the fishing season, lotus harvesting, making herbal teas, floating lanterns on rivers, and eating duck. In ancient paintings and calligraphy, regardless of whether it’s lotus roots or other famous works associated with fishing throughout history, there’s much to explore.

“A slight breeze under the fan, delicate hands peeling the lotus seed pods”

During Chushu, the lotus seed pods have already matured. The poem “Xizhou Qu” from the Southern Dynasties notes: “Gathering lotus in the southern pond in autumn, the lotus flowers rise above one’s head. Bowing down to play with lotus seeds, the seeds are as clear as water.”

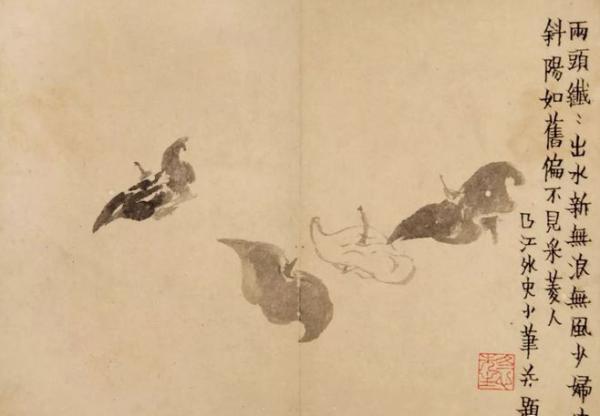

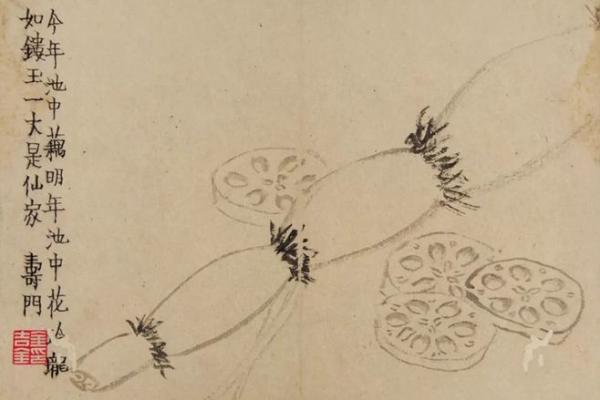

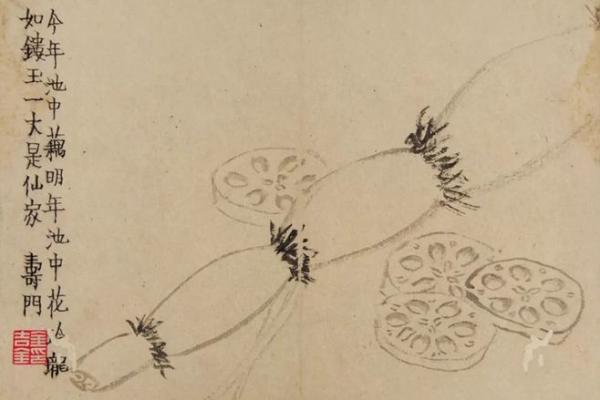

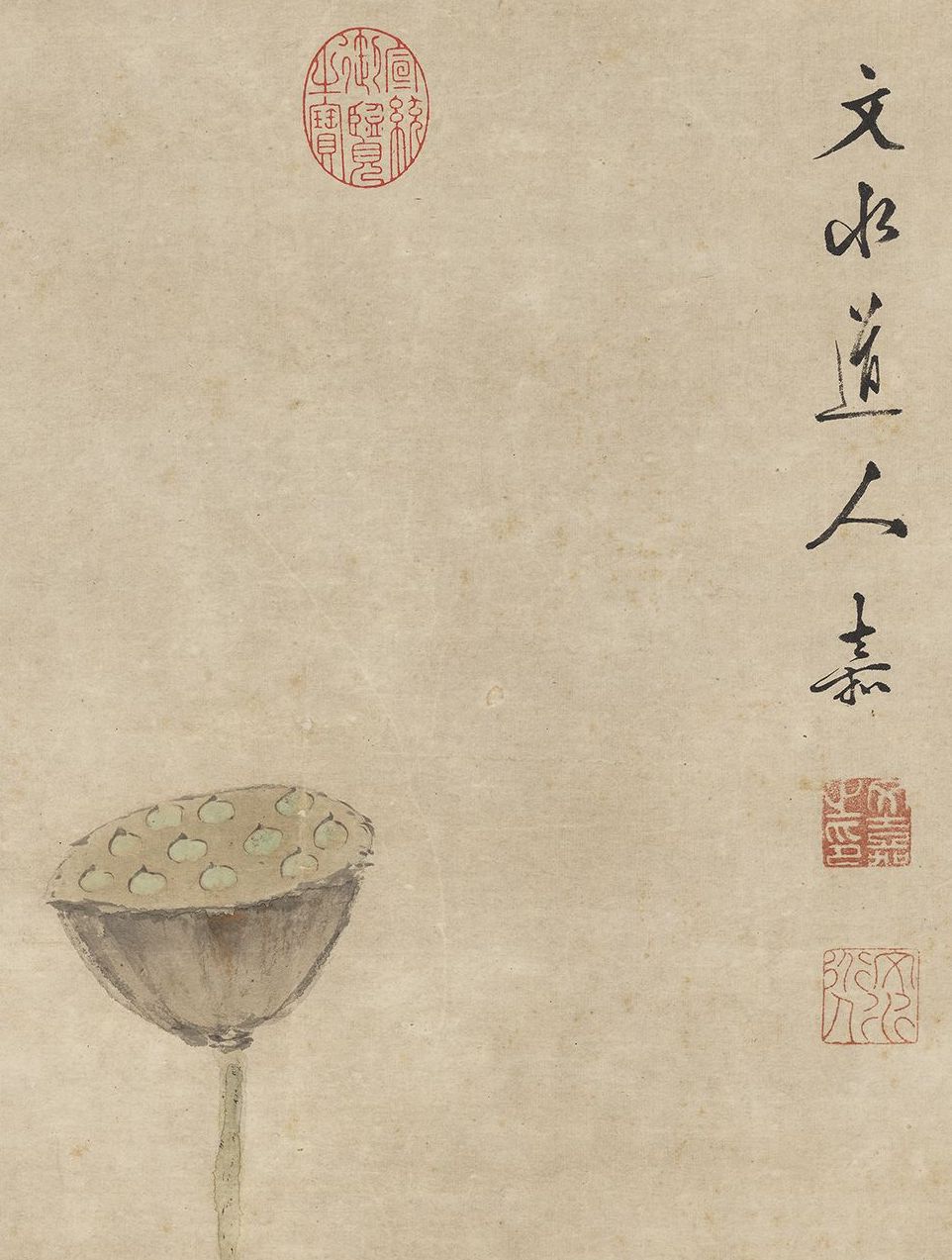

Jin Nong, one of the "Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou" during the Qing Dynasty, is fond of painting lotus seed pods. In the album "Ink and Wash Vegetables and Fruits" housed in the Jilin Provincial Museum, the sixth piece illustrates lotus roots and slices, outlined with light ink, exuding a refreshing and lively aura. It is inscribed: “This year’s lotus in the pond, next year’s flowers in the pond. Exquisite as carved jade, a yard is celestial. The Gateway of Longevity.” The eighth piece features two branches of lotus pods tied together, showcasing the textured appearance of the pods and stems. The inscription reads: “The lotus blossoms, the silver pond quietly grows cool early, how many emerald-winged dragonflies? The water window is clear, a slight breeze under the fan, remembering the moments shared with that person, delicate hands peeling the lotus seed pods. The Outer History of Qujiang writes a free verse and claims it can be set to music as well.”

Jin Nong's painting of lotus roots

Jin Nong's painting of lotus seed pods (detail)

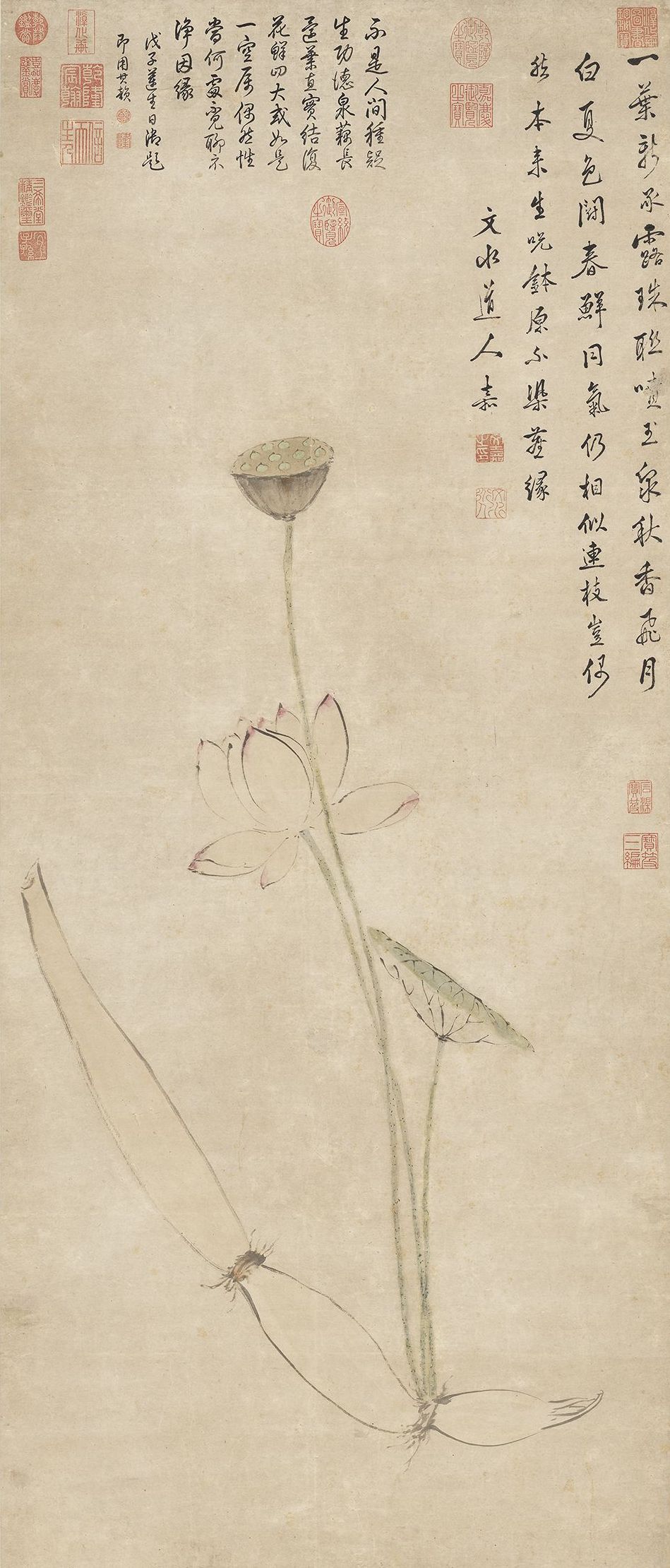

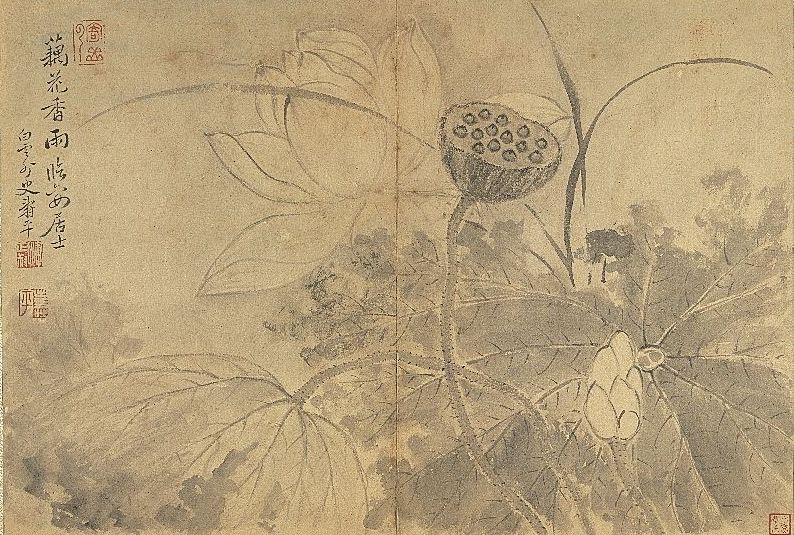

The Ming Dynasty artist Wen Jia has a work titled “Lotus and Cleansing Causes,” depicting a lotus root, a flower, and a bud with fresh brushwork. The Qing Emperor Qianlong inscribed in running script: “Not of this world, but born from the spring of merit. The lotus grows straight with its leaves, fruits mature yet flowers are brilliant. Are the four elements like this? Is emptiness mere coincidence? Where to seek nature? Let me show the cause of purity.”

Ming Wen Jia's painting of “Lotus and Cleansing Causes,” housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Ming Wen Jia's painting of “Lotus and Cleansing Causes” (detail), housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei

In the Qing Dynasty, Fu Shan’s “Ink Lotus” depicts an autumn lake with “splashed ink technique” used to create several lotus leaves, characterized by rich ink color and a watery feel. The lotus flowers and seed pods are depicted with fine brushwork, minimalistic yet evocative, exhibiting elegance amidst desolation. Below the painting, a stream flows gently, with slender reeds and grasses,creating a serene atmosphere. The inscription derives from Zhou Dunyi’s “A Poem on Love for the Lotus,” emphasizing the author’s identification with the lotus flower’s noble character. This work, lacking a date, is believed to be a product of Fu Shan’s later years, reflecting his spontaneous style of observation. Fu Shan became famous as a calligrapher, and his paintings, though less influential during the Ming and Qing periods, embody the typical characteristics of literati who indulged in the playful pursuit of ink painting, practicing the idea of “the unity of calligraphy and painting.”

The inscription reads: “Externally upright yet internally connected, fragrance far-reaching and increasingly pure. Mountainly written.” It bears the red seal “Seal of Fu Shan.”

Qing Fu Shan's “Ink Lotus” collection of the National Palace Museum

Yun Shouping (1633—1690) painted “Lotus,” depicting a lotus flower emerging from its green cover, complemented by lotus seed pods, using wet and dry brush techniques to show round leaves, slightly arranging veins, along with a dreamy watercolor effect that enhances the lightweight appearance of the lotus amid rain. This piece is the fifth in the album “Ink Masterpieces from Life,” with Yun Shouping’s inscription reading: “The fragrance of lotus flowers in the rain, visiting the recluse Liu Ru.”

Qing Yun Shouping’s “Lotus,” selected from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Yun Shouping’s “Ink Masterpieces from Life” album

Yun Shouping also created “The Divine Robe of Luopu,” from the National Palace Museum’s collection of Yun Shouping’s “Album of Flower Studies,” featuring a white lotus partially hidden by lotus leaves, delicately blooming. The subtle and refined brushwork captures the essence of the lotus, emphasizing the idea of remaining unstained despite growing from the mud. The term “Luopu” refers to the goddess of the Luo River from mythology, and the painting’s title signifies a personification of the flower. The lotus, also known as Water Hibiscus, reflects the artist’s deep affection as he referred to himself as “the Hermit of Hibiscus Creek.”

Yun Shouping’s “The Divine Robe of Luopu”

Boat Tied Among the Reed Clumps, a Gentle Breeze Carries the Fish Scents

As Chushu approaches, the annual fishing season begins along the coast. From the collections of the Palace Museum and the National Palace Museum in Taipei, artworks related to fishermen or fishing—from Ma Yuan’s “Returning to Fish at Qiupu” in the Song Dynasty to Fu Baoshi’s “Fishing Boats on Willow Creek”—offer a refreshing glimpse.

Song Ma Yuan's “Returning to Fish at Qiupu,” housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Song Ma Yuan's “Returning to Fish at Qiupu” (detail), housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei

The Southern Song painter Ma Yuan (1140–1225) created “Returning to Fish at Qiupu,” with a Qianlong running script inscription that reads: “The tied boat is set among the reed clumps, gathering baskets filled to the brim. Who knows this old man’s leisurely interest, as strands of hair drift in the fish-scented breeze.”

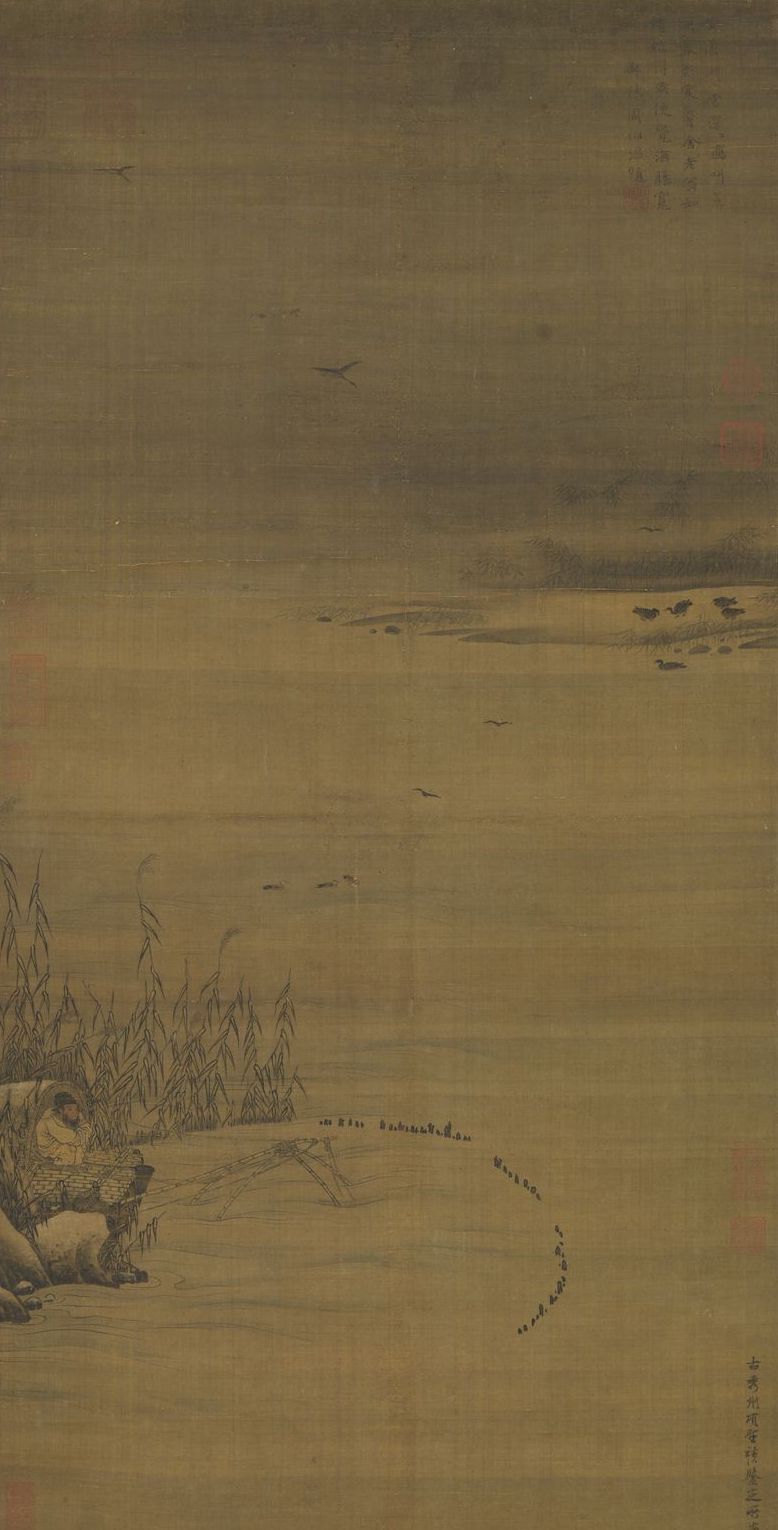

Song “Fisherman” painting, National Palace Museum collection, Taipei

The painting “Fisherman” portrays an expansive river scene, shrouded in mist, with reeds surrounding the shore and a few wild geese dotting the landscape, harmoniously connecting with the figure floating along the river, adding life to the radiant yet tranquil waters. The fisherman sits in a grass hut by the riverbank, arms crossed over his chest, leaning forward with his neck retracted, gazing at the water in anticipation of a catch, his expression vividly animated.

The Heat Begins to Fade, A Sense of Coolness Dawns

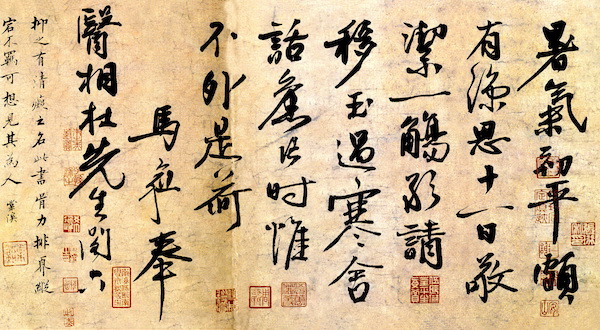

In the calligraphic works related to Chushu, Ming Dynasty artist Ma Yu’s “Summer Heat Post” (housed in the Palace Museum) invites his friend, Dr. Yi, to visit and reminisce. It reads, “The heat begins to fade, and a sense of coolness arises. On the eleventh, I will respectfully toast a drink, and I dare to ask you to come to my humble abode for a brief old-fashioned chat, primarily about the lotus.” The phrase “the heat begins to fade, a sense of coolness arises” encapsulates the essence of Chushu perfectly. This post has been collected by figures such as Zhu Zhiqi from the late Ming and An Qi from the Qing.

Little is known about Ma Yu’s life, but he was known as Yi Zhi, and took the sobriquet “Hua Fa Xian Ren,” or “Immortal with White Hair.” He hailed from Jiading (now Shanghai) and became a Jinshi in the eighth year of the Tianshun regime (1464) before serving as an official in the Ministry of Justice. A poet and writer, Ma was also skilled in calligraphy and landscape painting.

Ming Ma Yu’s “Summer Heat Post”

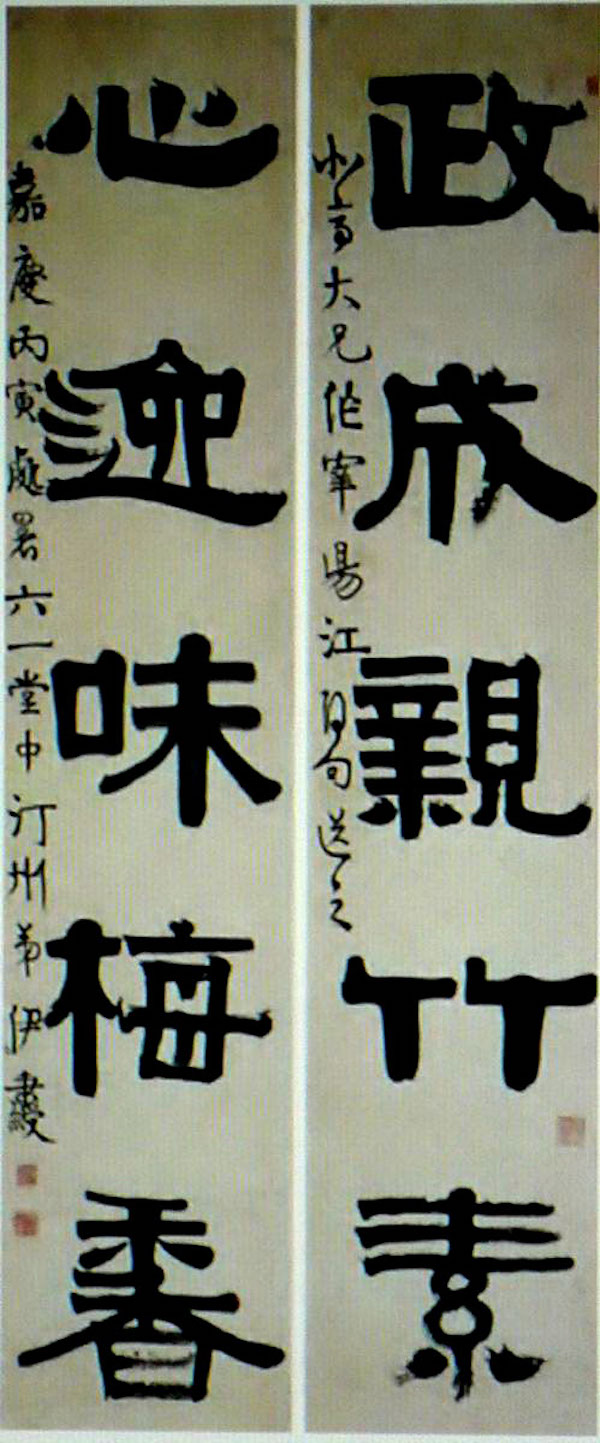

In the Qing Dynasty, Yi Bing shou’s couplet “Good governance enhances the bamboo’s purity, a heart filled with the fragrance of plums” was created during Chushu in the year of Bingyin, when he was 52 years old, showcasing a typical mature style. Yi Bing shou’s clerical script draws inspiration from Han stele, exhibiting a unique character. His vigorous and composed brushwork produces a solid and expansive structure with an elegant style. He summarized his style as: “square, strange, free-spirited, lighter, concise, void and solid, fat and thin, with varying pen strokes emerging from the wrist…” His couplets and hanging scrolls feature a rich interplay of sparsity and density, notable for its unique charm, revealing a strong personality and perfect symmetry. He adapted the brush techniques of seal script for his clerical script, resulting in smooth strokes that are evenly weighted, devoid of noticeable dips. His structuring style is distinctive, with every character fully formed, balanced and meticulous, giving a sense of decorative beauty, praised by Liang Zhangju as “the more massive, the more magnificent.”

Qing Yi Bing shou’s couplet “Good governance enhances the bamboo’s purity, a heart filled with the fragrance of plums” from the year of Bingyin during Chushu

(This article is compiled from relevant literature from the Palace Museum, customs associated with Chushu, and previous reports by The Paper.)