At the spring and autumn equinox, day and night are evenly balanced. Today marks the autumn equinox, the fourth solar term of autumn.

This year, the summer heat has lingered in many places for a long time. As the autumn equinox arrives, the day grows clear and bright, infused with a refreshing coolness. The poem “Yong Twenty-Four Solar Terms: Autumn Equinox in August” by Yuan Zhen from the Tang Dynasty serves as a barometer for this solar term, containing the lines, “Heaven and earth can be still and solemn; the cold and heat are harmonized and equal.” In Chinese art throughout history, representations of the autumn equinox, whether in the Dunhuang murals or Zhao Mengfu's “Autumn Colors over the Quehua,” evoke a captivating and timeless poetic quality. The Song Dynasty poet Lu You notes in his “Autumn Clarity Poem”: “This day of autumn is clear; we all appreciate the grand defenses. With divine help, may good fortune abound,” conveying greetings to friends... In the Yuan Dynasty, Qian Xuan inscribed on “Waiting for the Ferryman on the Autumn River” that “the mountains appear hazy and the greens seem to flow, the Yangtze River drenched in a day of autumn.”

During the autumn equinox, the remaining heat comes to an end, and day and night stand at balance. The grass and trees turn yellow, and flocks of geese fly across the autumn sky. At this time, pears, persimmons, and water chestnuts are harvested, with pomegranates ripening on the branches overnight and wild persimmons turning red by morning.

Autumn day filled with red persimmons Photo by The Paper

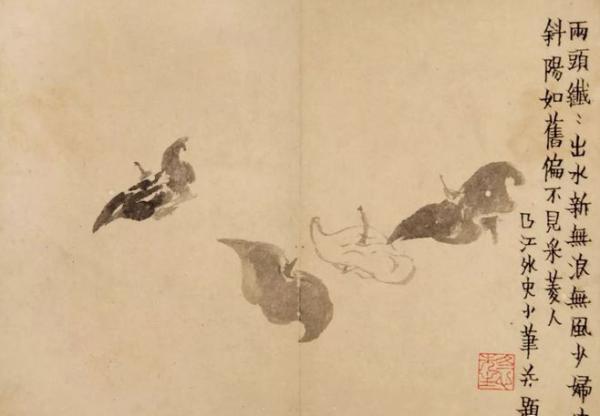

“Six Persimmons” by Mu Xi Photo by The Paper

Around the autumn equinox, there are folk customs such as moon worship, eating autumn vegetables, and sending off autumn cattle. The autumn equinox is closely linked to agricultural activities, with a folk saying, “White dew comes early, cold dew comes late; planting wheat is just right around the autumn equinox.” Because the autumn equinox is one of the important days for ancient Chinese farmers to predict harvests, a custom known as “autumn equinox divination” developed. The simplest method of divination was observing the weather. If the day of the autumn equinox was cloudy with a light rain, it indicated a good harvest. A proverb recorded by Gu Lu in his “Qingjia Record: August” notes, “After the equinox, white rice is found everywhere; before the equinox, white rice becomes like a golden mound.” Local records explain: “If the equinox is before the festival, the crops will be fruitful but grain will be cheap; if it is after, there will be no harvest and grain will be costly.”

On the day of the autumn equinox, there is also a custom called “sending off the autumn cattle.” On this day, skilled storytellers, with prepared autumn cattle drawings (printed on red or yellow paper featuring farmers plowing the fields and a depiction of the year's solar terms), begin their “cow sending” activities paired with performances.

Plowing cattle, Mogao Caves, Cave 117, Mid-Tang Dynasty

Two Cattle Fighting, Yulin Caves, Cave 25, Mid-Tang Dynasty

In the murals of Mogao Cave 249, wild cattle confidently walk through the forest, some startled, captured by the brush strokes of the artist with just a few quick lines. One muscular and lively wild cattle seems as if it is about to step right out of the mural.

Golden Cattle, Mogao Caves, Cave 61, Yuan Dynasty

The autumn equinox was previously established as “China's Farmers' Harvest Festival,” a name that brings comfort and joy. The happiness is not just felt by the farmers working tirelessly in the fields but also welcomed by the cattle, who enjoy their leisure time in the year. In the “Plowing and Weaving” by Qing Dynasty painter Chen Mei, the scenes of harvesting, showcasing, and storing details the glory of a farm's harvest and the joy that comes with it, encapsulated in the saying, “In the frosty mornings, neighbors call to one another; all around the village, the sound of rice harvesting is heard.”

In the Dunhuang murals, a story originally depicting the high monk Kang Senghui arriving in China via the sea during the Three Kingdoms has been transformed by the artist into a picturesque scene of boating on the lake. With shimmering reflections and mountain scenery, a light boat floats while the autumn wind fills the sail, evoking a sense of leisure in the autumn outing.

The renowned work in the history of Chinese literati painting, “Autumn Colors over the Quehua,” exemplifies the distant and clear qualities of autumn. This painting was created by Yuan Dynasty artist Zhao Mengfu in 1295, when he returned to his hometown in Zhejiang to make it for his friend Zhou Mi. Now housed in the Taipei National Palace Museum, it depicts the autumn scenery around Huazhu Mountain and Qiao Mountain northeast of Jinan, capturing a sense of calm and idyllic rural charm. Utilizing a flat perspective, it employs various colors for rendering, harmonizing light and shadow, with elegant brushwork rich in rhythm. The two peaks in the painting, with Qiao Mountain in muted flower cyan and Huazhu Mountain in faint green, stand out against the backdrop. The surrounding elements such as islets and trees are painted with varying shades of green, while houses, cattle, and some leaves are depicted in warm colors of red and yellow that merge cold and warm tones, showcasing both the autumn's fresh purity and the harmony of human sentiments.

Detail from the Yuan Dynasty “Autumn Colors over the Quehua”

The autumn equinox has also historically been recognized as a traditional “Moon Festival,” which evolved from the moon worship of the autumn evening. In ancient times, there were customs of “spring worship of the sun and autumn worship of the moon.” In ancient Zhejiang, besides moon gazing after the autumn equinox, watching the tides could be considered another significant happening, which can be seen in the paintings of Li Song from the Song Dynasty.

“Viewing the Tide on a Moonlit Night” by Li Song

Among famous paintings depicting autumn scenes through the ages, there is the “Autumn Mountain Seeking the Way” by Ju Ran from the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties. This artwork portrays mounds of earthy mountains that appear rounded and gentle rather than steep cliffs, with an oval-shaped boulder called “alum head” at the peak. Using long arc-shaped lines to depict the mountains and stones, employing a technique called “pimma” (a kind of thin-layered brushwork), the brushstrokes are fluent, primarily in light ink, exuding a refreshing and subtle charm. The painting also features secluded streams and cottages, capturing the scenic beauty of southern China.

“Autumn Mountain Seeking the Way” by Ju Ran from the Southern Tang, housed in the Taipei National Palace Museum

The “Autumn Deer in the Maple Forest” (no artist attributed) from the Five Dynasties, housed in the Taipei National Palace Museum, depicts a delightful scene of deer frolicking and resting amid the autumn maple trees. Its style is quite distinctive, differing from traditional methods, suggesting foreign influence with a strong decorative flair. The deer are painted with faint ink washes, while the leaves are outlined first with fine strokes before being washed with green ink or filled with color, resulting in a rich yet delicate aesthetic, creating an impression of exquisite elegance.

“Autumn Deer in the Maple Forest” (detail) from the Five Dynasties, housed in the Taipei National Palace Museum

“Autumn Scenery” by Zhao Boju from the Song Dynasty

The “Autumn Scenery” scroll by Zhao Boju from the Song Dynasty bears seals from the Qianlong Collection of the Qing court and other notable collections. At the end of the scroll, there is an inscription from the Ming Hongwu period (1375). The work, rendered in green and blue, features green mountains and clear waters, temples and cottages interspersed with pathways and bridges, alongside verdant pines and cypress trees, creating a picturesque scene that delights the viewer. The rocks are depicted using an ax-cutting technique, filled with rich green tones, while the trees and buildings showcase meticulous and refined details. The use of detailed figures enhances the narrative, with the overall composition grand, rich in detail, vibrant in color yet remaining elegant, reflecting the characteristics of the Song court’s painting style.

Autumn has always been a season for poets to express sentiments and reflections, often mixing tender melancholy with grand emotions. The Song Dynasty poet Zhang Yan wrote: “As the moon sets, the sand flat, the river flows like a silken ribbon; gazing into the reeds, no geese can be seen. Darkly teaching sorrow to diminish the orchids, pity the feelings for the night’s closing. Only a branch of parasol leaves remains, unaware of how many autumn sounds echo.” Although Su Shi was an optimist, he occasionally could not escape feelings of melancholy, “Life is but a great dream; how many seasons of autumn chill does one experience?” Although he does not directly mention autumn, his sentiments reflect a profound sense of desolation.

The “Autumn Clarity Poem” by Lu You from the Song Dynasty, written during the sixth year of the Qiandao era (1170), is addressed to his friend Zeng Feng, also known as Yuanbo. In it, he writes: “My humble regard has never waned. Today, autumn is clear; we all appreciate the grand defenses, with divine assistance may good fortune abound. I will only be able to arrive at Wuchang towards the end of August. On my journey, it is hard to surpass this; I only hope to share exquisite words for farewell.” “Today, autumn is clear; we all appreciate the grand defenses, with divine assistance, may good fortune abound,” expresses greetings to his friend, while indicating that Lu You had once visited Wuchang, at the